Cutting Red Tape in Canada: A Regulatory Reform Model for the United States?

Canada recently became the first country in the world

to legislate a cap on regulation. The Red Tape Reduction Act, which

became law on April 23, 2015, requires the federal government to

eliminate at least one regulation for every new one introduced.

Remarkably, the legislation received near-unanimous support across the

political spectrum: 245 votes in favor of the bill and 1 opposed. This

policy development has not gone unnoticed outside Canada’s borders.

Canada’s

federal government has captured headlines, but its approach was

borrowed from the province of British Columbia (BC) where controlling

red tape has been a priority for more than a decade. BC’s regulatory

reform dates back to 2001 when a newly elected government put in place

policies to make good on its ambitious election promise to reduce the

regulatory burden by one-third in three years. The results have been

impressive. The government has reduced regulatory requirements by 43

percent relative to when the initiative started. During this time

period, the province went from being one of the poorest-performing

economies in the country to being among the best. While there were other

factors at play in the BC’s economic turnaround, members of the

business community widely credit red tape reduction with playing a

critical role.

The British Columbia model, while

certainly not perfect, is among the most promising examples of

regulatory reform in North America. It offers valuable lessons for US

governments interested in tackling the important challenge of keeping

regulations reasonable. The basics of the BC model are not complicated:

political leadership, measurement, and a hard cap on regulatory

activity.

This paper describes British Columbia’s

reforms, evaluates their effectiveness, and offers practical “lessons

learned” to governments interested in the elusive goal of regulatory

reform capable of making a lasting difference. It also offers some

important lessons for business groups and think tanks outside government

that are pushing to reduce red tape. These groups can make all the

difference in framing the issue in such a way that it can gain wide

support from policymakers. A brief discussion of the challenges of

accurately defining and quantifying regulation and red tape add context

to understanding the BC model, and more broadly, some of the challenges

associated with effective exercises in cutting red tape.

Defining Red Tape

Red

tape refers to rules, policies, and poor government services that do

little or nothing to serve the public interest while creating financial

cost or frustration to producers and consumers alike. Red tape may

include poorly designed laws, regulations, and policies; outdated rules

that may have been justified at one time but are no longer; and rules

intentionally designed to burden some businesses while favoring others.

Red tape, as the term is used in this paper, stands in contrast to

government laws, regulations, rules, and policies that support an

efficient and effective marketplace and provide citizens and businesses

with the protections they need. For the sake of keeping a clear

distinction between the two, the latter will be referred to as

“justified regulation” in this paper. The “broad regulatory burden” is

composed of both justified regulation and red tape.

Some

rules fall into the justified regulation category because they deliver a

lot of benefits relative to their costs. Others, such as an eliminated

BC regulation prescribing what size televisions BC restaurateurs could

have in their establishments, have little or no value and entail

significant compliance costs, so they fall into the category of red

tape. However, the difference between justified regulation and red tape

is not always straightforward in the messy real world where costs and

benefits are not always easily quantified and one person’s red tape is

another person’s justified regulation.

Despite

measurement challenges, available evidence suggests that the broad

regulatory burden is growing in both Canada and the United States. Given

that red tape delivers very little benefit relative to its costs, it is

reasonable to want to keep this piece of the broad regulatory burden to

a minimum. This is easy to say but hard to do for a number of reasons.

Part of the challenge can be attributed to the loose language that is

often used about regulatory reform, especially the imprecise use of the

terms regulation and red tape. People sometimes confuse

cutting red tape, which most support at least in theory, with

eliminating justified regulation, which most do not support in theory or

practice.

In Canada, the language about government

reform has evolved to put a heavy emphasis on the distinction between

red tape and necessary or justified regulation, as exemplified in the

title of the recently passed Red Tape Reduction Act. The Canadian

Federation of Independent Business (CFIB), a not-for-profit small

business advocacy group with 109,000 small business members, strongly

promotes this distinction in its work with governments. For example, in

2010 it created an annual Red Tape Awareness Week to highlight the costs

of red tape and to tell the stories of business owners affected by it.

Politicians at both the provincial and federal levels of government make

announcements about cutting red tape (as opposed to announcements about

regulatory reform) during the week. For example, during the 2011 Red

Tape Awareness Week, former prime minister Stephen Harper announced the

creation of a Red Tape Reduction Commission (which ultimately led to a

number of reforms, including the one-in, one-out legislation explained

above). The BC government used the 2015 Red Tape Awareness Week to

announce that it was extending its policy of eliminating one regulatory

requirement for every new one introduced to 2019 (it had been set to

expire in 2015).

Quantifying Regulation and Red Tape

Governments

have three main ways of influencing behavior: taxing, spending, and

regulating. All have benefits and costs. With taxation and government

spending, however, the costs and benefits are more obvious. It is clear

how much money the government collects in revenues and there is a high

degree of transparency with respect to how the money is spent, although

it can be tougher to evaluate outcomes of spending and the externality

costs and benefits to third parties. The costs of the broad regulatory

burden and its two components, justified regulation and red tape, are

considerably less clear. Much of the costs fall on those who must comply

with the rules, and these costs are never quantified by governments,

making them essentially a hidden tax. Regulatory benefits too can be

challenging to quantify.

The challenges of measuring

regulatory costs and benefits are not trivial because they make it

difficult to assess how much the broad regulatory burden is costing,

whether the costs are increasing, and how much of the broad regulatory

burden is red tape. In spite of ongoing concern from business

communities in both the United States and Canada that regulatory costs

are too high and growing, governments tend to be reluctant to take the

first necessary step to assess the burden: that is, to measure it.

Reducing regulatory excess without measurement is like trying to lose

weight without ever stepping on a scale—possible but not probable. A

distinguishing feature of the BC model, discussed in the next section,

is the government’s willingness to create and track its own measure of

the broad regulatory burden.

While governments have

been generally reluctant to quantify the regulatory burden, others have

stepped up to the challenge, including researchers working for the

Canadian CFIB, as well as the Mercatus Center at George Mason

University, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and the Small Business

Administration’s Office of Advocacy in the United States. Existing

measures, albeit limited and imperfect, bring some valuable transparency

to our understanding of the broad regulatory burden. Clyde Wayne Crews,

author of numerous studies on the broad burden of regulation, explains,

Precise regulatory costs can never be fully known because, unlike taxes, they are unbudgeted and often indirect. But scattered government and private data exist about scores of regulations and about the agencies that issue them, as well as data about estimates of regulatory costs and benefits. Compiling some of that information can make the regulatory state somewhat more comprehensible.

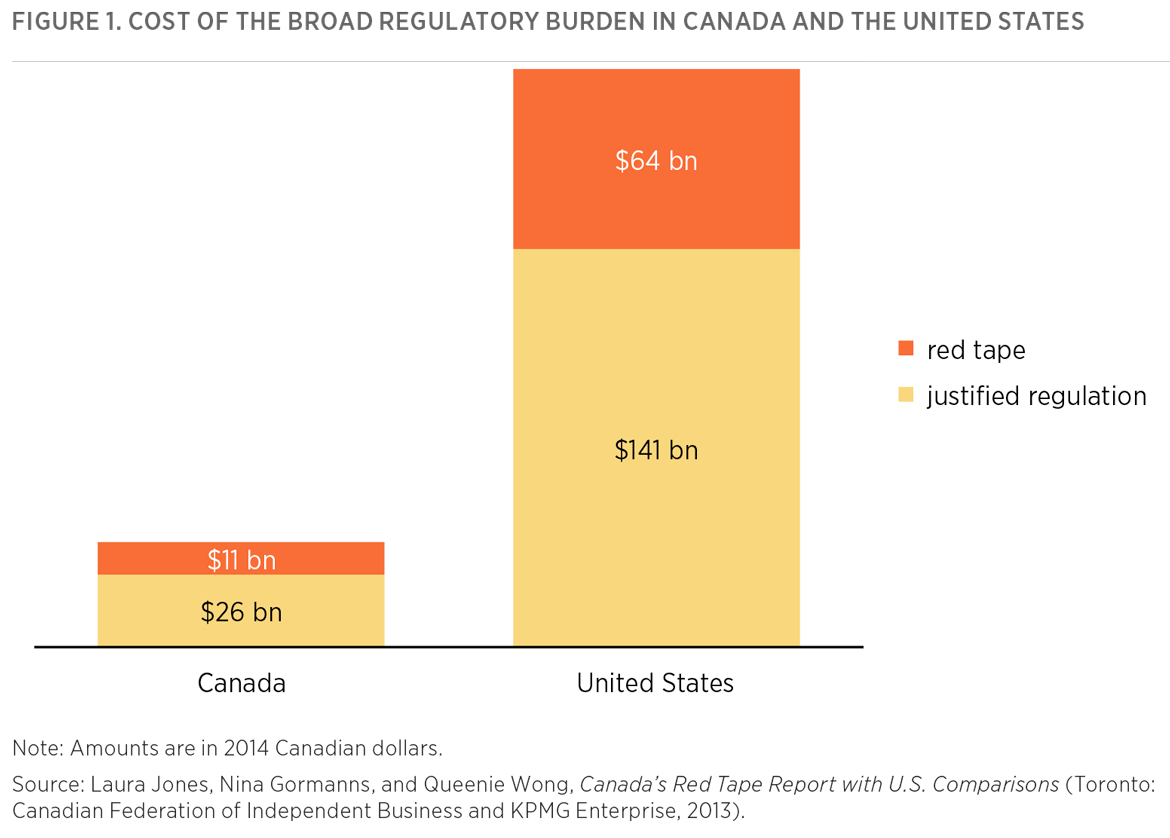

Using

survey results from both Canada and the United States, CFIB estimates

that broad regulatory costs for US businesses are around C$205 billion

while Canadian businesses, far fewer in number, pay C$37 billion a year.

What fraction of these broad costs might constitute red tape? When US

small businesses were asked how much of the burden of regulation could

be reduced without sacrificing the public interest for these

regulations, the average response was a 31 percent reduction (or C$64

billion a year) with Canadian respondents sharing a similar view on the

fraction of the broad regulatory burden that is red tape (see figure 1).

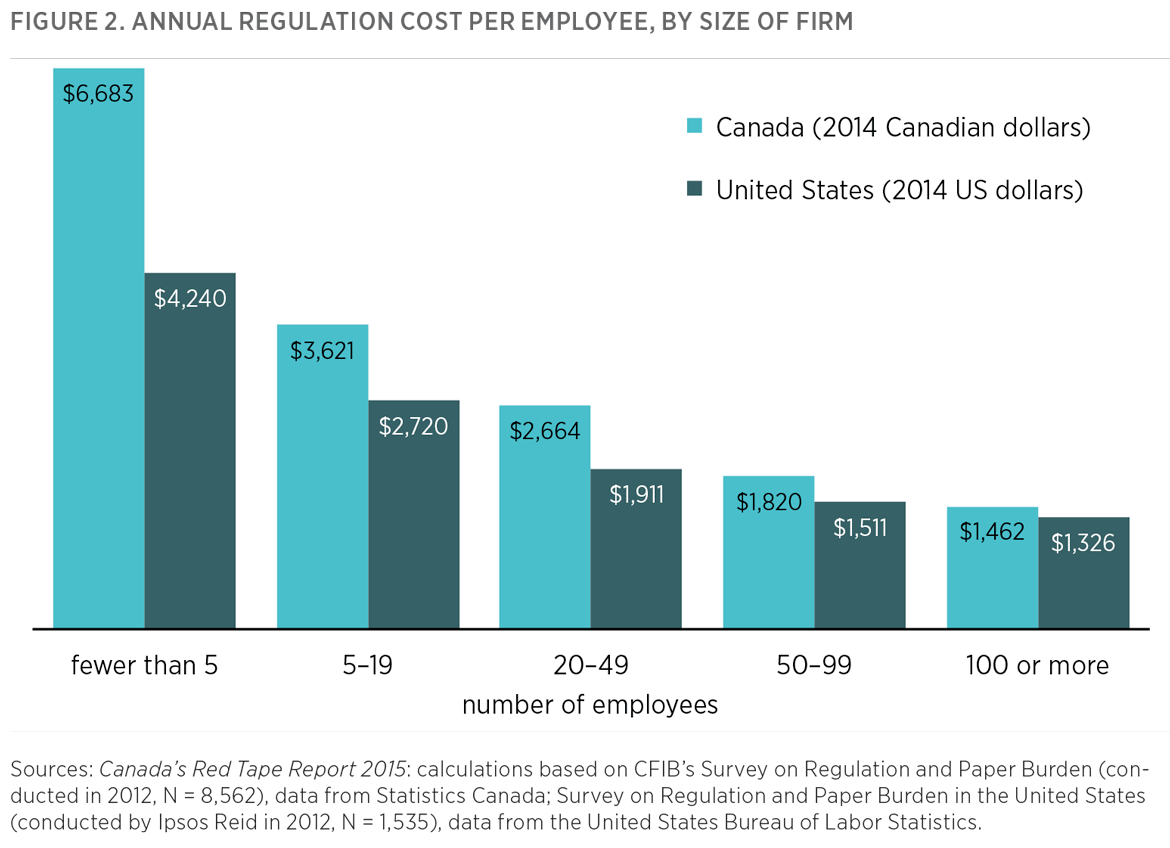

The survey results are consistent with the findings of other studies,

showing that the smallest businesses in both countries pay considerably

higher per-employee regulatory costs than larger businesses do (see

figure 2).

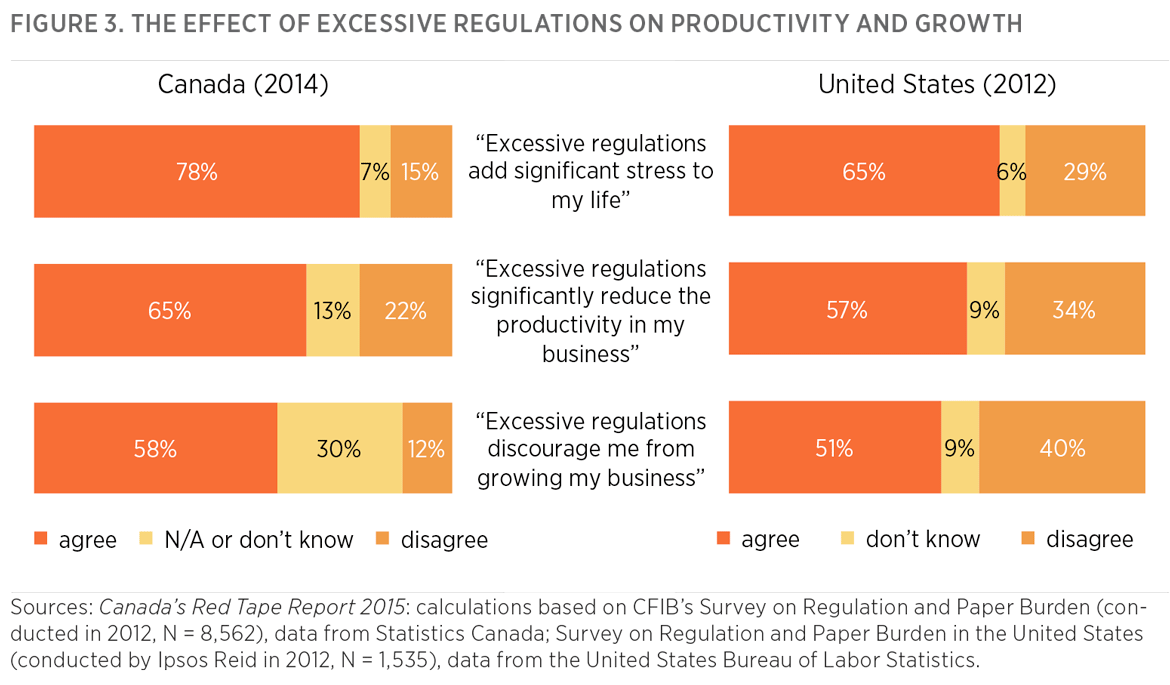

The

same CFIB survey found that more than half of US small businesses (57

percent) agree that excessive regulations (or red tape) significantly

reduce business productivity while 65 percent of Canadian businesses

agree with the same statement. A significant portion of respondents in

both countries indicate excessive regulations discourage businesses

growth. Beyond the economic costs, small business owners find regulatory

compliance very stressful, with 78 percent of Canadian respondents

agreeing that excessive regulations add significant stress to their

lives and 65 percent of US respondents agreeing (see figure 3).

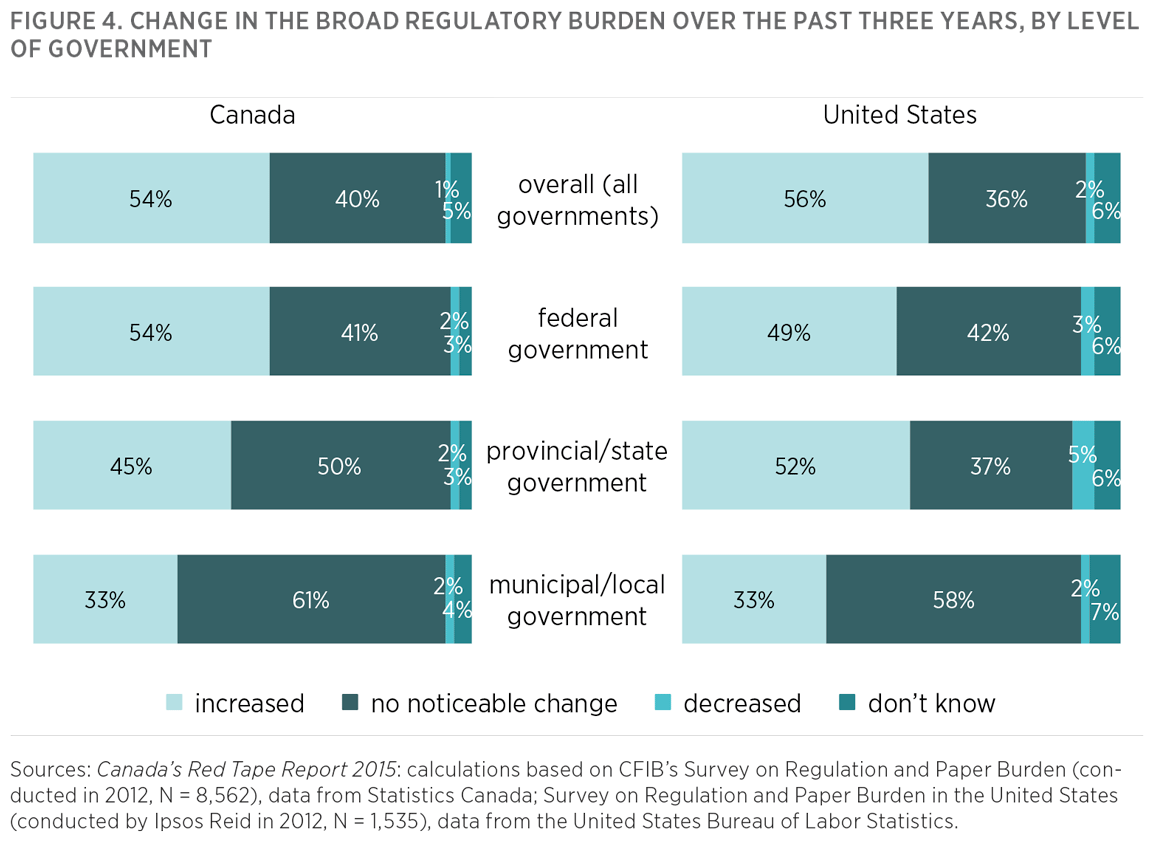

In

both Canada and the United States, far more businesses believe the

burden of regulation is growing or staying the same than those that

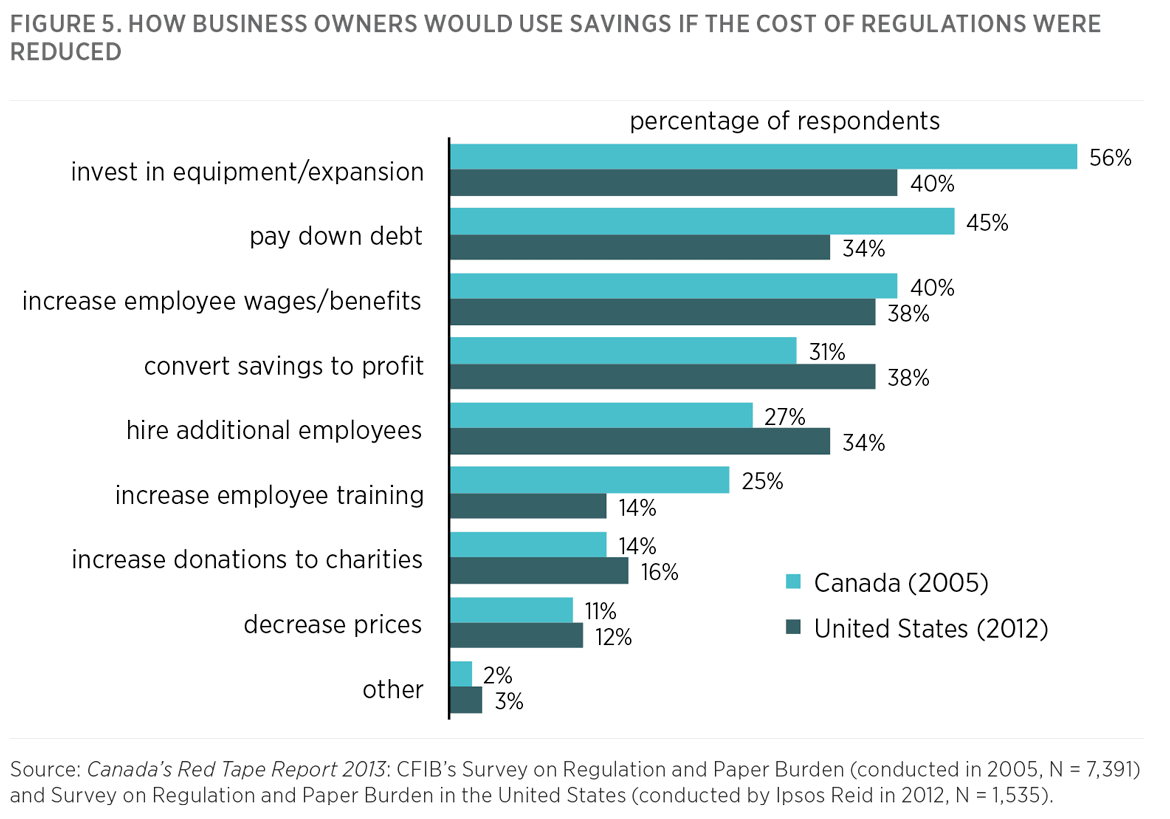

believe it is decreasing (see figure 4). Figure 5 shows how business

owners say they would use savings if the cost of regulation was reduced.

Investing in equipment and expanding the business is the most commonly

cited use for the savings, another indication that reduced regulatory

costs could enhance productivity.

A

very different way to quantify the broad regulatory burden is to track

it by volume—by counting the number of regulations, the number of

requirements associated with regulations, or the number of pages of

regulations. An example of the approach of counting the number of

regulatory restrictions is the Mercatus Center’s database called

RegData, which counts the number of regulatory restrictions in the Code of Federal Regulations

(using a count of restrictive terms such as “shall not” and “must”).

According to its data, as of 2012, there were 1,040,940 restrictions in

the Code of Federal Regulations, an increase of 28 percent since

1997. RegData also quantifies how many additional restrictions are in

place as a result of new laws such as the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform

and Consumer Protection Act, which has added over 27,000 new federal

restrictions since 2010, compared to all other laws passed by the Obama

administration (roughly 25,500). RegData considers only federal

regulations (as mentioned previously, government rules also can exist in

legislation and other government policies), and it does not attempt to

differentiate red tape from justified regulation. The Mercatus database

has the advantage of being more objective than survey-based approaches,

as it does not rely on perceptions and estimates of time and money spent

on regulation.

Using yet another approach with a more

complex methodology, Nicole Crain and Mark Crain wrote a report for the

Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy, in which they

estimate that the cost of federal regulations in the United States in

2008 was $1.75 trillion (14 percent of US GDP), up from $1.1 trillion in

2005 and $843 billion in 2001. The cost of US regulation in this study

is significantly larger than the estimate from the survey-based approach

of the CFIB, underscoring how challenging it is to estimate regulatory

costs.

The US Congress requires the Office of

Management and Budget to submit a report each year estimating the annual

benefits and costs of federal regulation to the extent feasible. The

report for 2014 estimates the benefits of federal regulation to be

between $217 billion and $863 billion from October 1, 2003, to September

30, 2013, while the costs over the same period are estimated at

somewhere between $57 billion and $84 billion (in 2001 dollars).

However, the estimates only cover a small fraction of the total rules.

Richard Williams and James Broughel find that for fiscal years

2003–2012, OMB reported both cost and benefit numbers for only 0.3

percent of the regulations. Both the wide range of the estimates and the

limited scope of what they cover once again underscore the challenge of

quantifying the costs and benefits of regulation.

The

standard cost model, initially used in the Netherlands, is a way of

measuring part of the overall regulatory burden. Popular with European

governments, this model estimates the amount businesses spend

administering regulations, but it makes no attempt to divide the

regulations into those that are legitimate and those that would be

considered red tape. Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway have used the

model to track progress toward their respective reduction targets of 25

percent. Although some European countries have embraced the model as a

credible way to measure, it does have drawbacks. The methodology is

complex (the user’s guide is 63 pages long) and it is much more

difficult to implement than the BC measure discussed in the next

section.

This brief discussion of some of the

available measures of the regulatory burden leads to two important

conclusions. First, measuring the broad regulatory burden, and

determining what portion of that burden may constitute red tape, is a

challenging and imperfect undertaking. However, measurement is also an

essential part of effective red tape reduction. One of the difficulties

that governments interested in effective red tape reduction face is

finding a clear, credible measure they can be comfortable using in spite

of its inevitable imperfections. Second, available evidence suggests

that the broad regulatory burden, including red tape, is large and

growing, and that reducing red tape is a worthy policy objective. Both

of these observations make the BC model of red tape reduction discussed

below very relevant.

British Columbia’s Experience with Red Tape Reduction

British

Columbia is Canada’s westernmost province, with a population of 4.6

million people (roughly the same population as Louisiana) and a GDP of

approximately C$220 billion. BC’s small open economy is reasonably well

diversified, with important sectors including forestry, mining, oil and

gas, agriculture, tourism, financial services, real estate, technology,

and film products.

The context for BC’s experience

with regulatory reform was set in the 1990s, a time widely known as BC’s

“dismal decade,” when economic growth and employment lagged behind the

rest of the country. The New Democratic Party government came to power

in 1991 and raised taxes and increased regulation. The attitude of the

government toward the economy in the 1990s is captured well by the

comments of former premier Glen Clark, who was in power for most of that

period. Shortly after leaving office, he told a reporter, “We were an

old-fashioned activist government, with no more money. So you’re

naturally driven to look at ways you can be an activist without costing

anything. And that leads to regulation.”

It is no

surprise that, during this period, too much regulation or red tape was

often cited as a significant contributor to BC’s economic

underperformance, and the province had a reputation within Canada for

regulatory excess. Forest companies were told what size nails to use

when building bridges over streams. Restaurants were told what size

televisions they could have. Golf clubs had to have a certain number of

par-four holes, and the maximum patron capacity for ski hill lounges was

based on the number of vertical feet it took to get to the top of the

mountain.

The forest industry, one of the province’s

main economic drivers, was burdened with a prescriptive Forest Practices

Code that was widely cited as a deterrent to investment. According to

one estimate, forestry regulations had added over $1 billion to the

industry’s costs with no public benefit. The mining industry, another

economic driver, was also suffering. In a 1998 survey of mining

companies, British Columbia’s overall investment policies scored last

out of 31 jurisdictions on an investment attractiveness index, receiving

a score of 5 points out of a possible 100. BC was the worst

jurisdiction on several red tape indicators contributing to the index,

such as “uncertainty concerning the administration, interpretation and

enforcement of existing regulations” (76 percent indicated this was a

strong deterrent to investment), and “regulatory duplication and

inconsistencies” (62 percent indicated this was a strong deterrent to

investment).

Elections in British Columbia tend to be

quite close, but in 2001 concern over the economy—including

uncompetitive tax and regulatory policies, deficits, and costs of

infrastructure projects—contributed to a landslide victory of the

Liberal Party (a center-right coalition) over the incumbent New

Democratic Party (a left-of-center party) that had been in power since

1991; 77 of 79 seats in the election were won by Liberal candidates.

The Early Years of Red Tape Reduction in British Columbia: 2001–2005

During

the 2001 election campaign, the soon-to-be-elected Liberal government

made the commitment to reduce the regulatory burden by one-third in

three years. Once elected, Premier Gordon Campbell wasted no time in

taking steps to accomplish his government’s goal. In his first cabinet,

the premier appointed Kevin Falcon to the newly created position of

minister of state for deregulation. Falcon’s only responsibility was

regulatory reform, and he reported regularly at cabinet meetings.

The

choice of the strong word “deregulation” reflected the context in which

the reforms were undertaken—a province emerging from a “dismal decade”

needed big policy changes. The minister of deregulation’s first

challenge was to develop a new regulatory policy and to figure out what

measure the government would use to determine the success of its

commitment to reduce the regulatory burden by one-third. Over time, the

language changed from “deregulation” to “regulatory reform” and “red

tape reduction.”

Falcon rejected several crude

regulation measures used by think tanks and academics in the past. For

example, he decided not to count pages of regulations or to simply count

regulations, as each individual regulation can have literally thousands

of requirements associated with it. To understand the difference

between counting “regulations” and counting “regulatory requirements,”

consider that the Workers Compensation Act (legislation governing

workplace safety) has nine regulations associated with it, but these

nine regulations contain 35,308 regulatory requirements.

The

minister chose to use regulatory requirements as his counting tool. The

regulatory requirement measure was unique to BC at the time. It is

similar to the measure that the Mercatus Center is now using for its

RegData project. One important difference between the RegData measure

and the BC measure is that BC’s measure included requirements found in

policies and legislation as well as in regulations, so it is quite

comprehensive. A “regulatory requirement” is defined in BC’s Regulatory

Reform Policy (see attachment) as “an action or step that must be taken,

or piece of information that must be provided in accordance with

government legislation, regulation, policy or forms, in order to access

services, carry out business or pursue legislated privileges.” For

example, writing your name on a form or being required to have a safety

committee meeting would each count as one regulatory requirement. To

develop a baseline count of regulatory requirements, each ministry

conducted its own count of all the regulatory requirements contained in

the statutes, regulations, and policies that ministry oversaw. A central

regulatory requirement database, administered by the newly created

Deregulation Office, was established to track progress against the

baseline and issue regular reports. The first government-wide count

revealed 382,139 regulatory requirements (the regulation count, which

was not used, would have been a much less compelling 2,200).

The

regulatory requirement measure has several advantages, including its

simplicity and granularity relative to the much cruder regulation

measure. However, like other measures, it has its flaws. For example, a

regulatory requirement could be something that only a few people have to

do once a year or it could be something that many people have to do

multiple times a year. The impact of these requirements is vastly

different, yet each would count as one regulatory requirement. The

measure could evolve to include frequency of reporting.

Setting

a clear target for regulatory reduction and establishing a clear and

compelling measure for evaluating success are two things that

differentiate BC’s regulatory reform initiative from other initiatives.

In contrast, many regulatory reform initiatives focus on identifying

specific irritants. These initiatives have a track record of failing to

make much difference because, as the specific irritants are dealt with,

others proliferate—the equivalent of pulling a few weeds in an overgrown

garden.

One example of this is the prior BC

government’s announcement in the 1998 budget that cutting red tape would

be a priority. The government set up the Small Business Task Force,

which focused on specific initiatives such as streamlining filing and

registration requirements and simplifying approval processes. These are

worthy objectives, but it is hard to see how they contribute to an

overall reduction without the discipline of an aggregate measure in

place.

Another common approach to regulatory reform is

to institute some form of regulatory impact analysis (RIA) that is

essentially an internal checklist for regulators who must go through the

exercise of evaluating the costs and benefits of new regulations. The

United States and Canada, as well as many other developed countries, use

a form of RIA process at the federal and state or provincial level (not

all US states have a RIA process). While RIAs may improve the

regulatory process, they have not proved an effective approach for

reducing red tape for at least three reasons: they are not subject to

much public scrutiny, they do not cover a broad enough scope, and they

set no overall limit on the total volume of regulatory activity.

Of

course having a measure is not enough, it also must be monitored. In

BC’s case, the measure was monitored closely. During the initial years

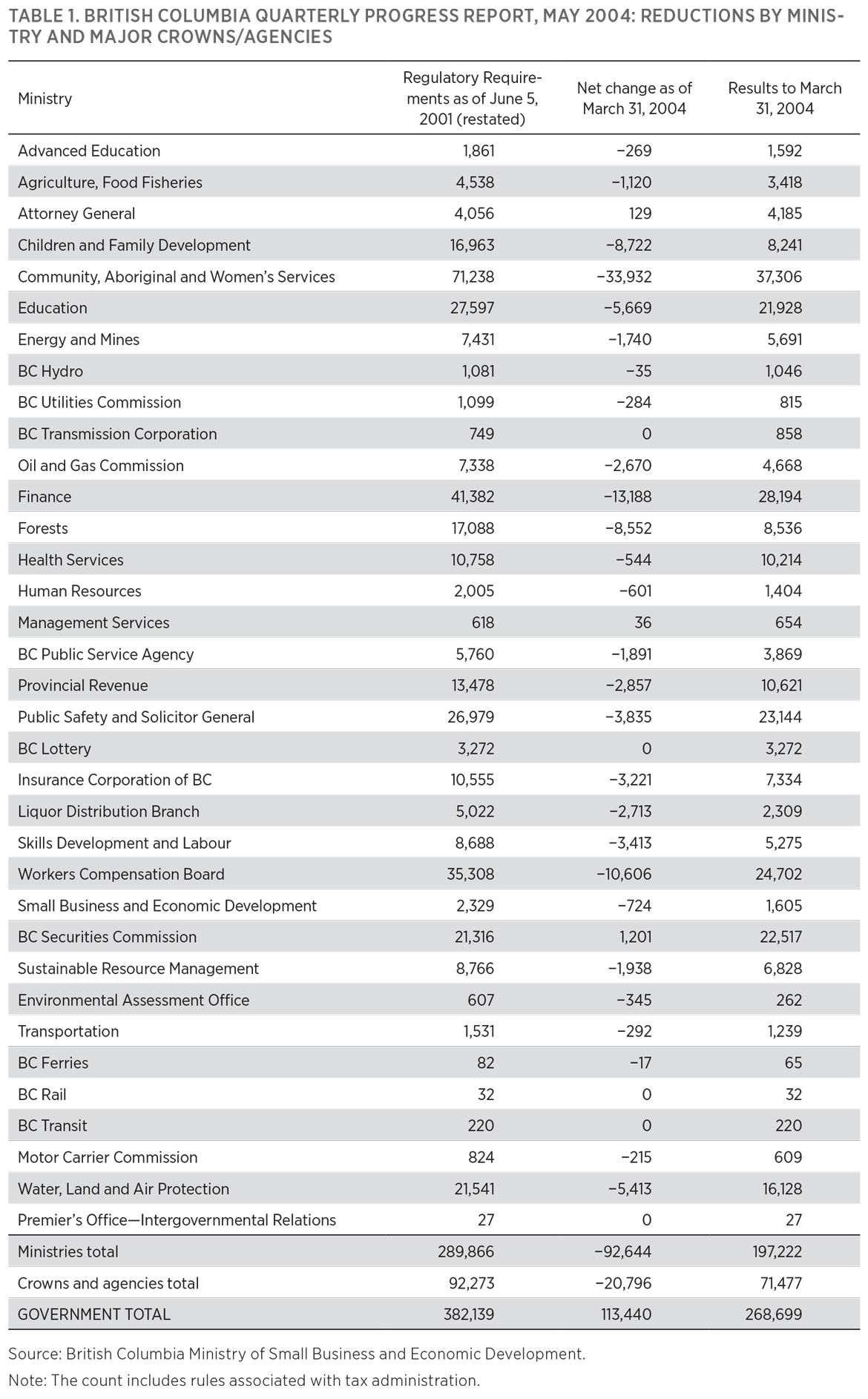

of the reform, the BC government publicly issued quarterly reports

showing how many regulatory requirements each ministry had reduced.

Table 1 is a quarterly report from May 2004. The reports were discussed

regularly at cabinet meetings and created a strong culture of

accountability across government.

Measurement

was critical to assessing whether the political commitment of reducing

the regulatory burden by one-third had been met, and it was the

cornerstone of the government’s overall Regulatory Reform Policy

(attached), which was approved by Executive Council in August 2001, just

three months after the election. The Reform Policy applies to all

proposed legislation, regulations, and related policies. This broad

application is another important feature of BC’s reforms because much of

what the private sector experiences as regulatory burden is in the form

of policies and forms rather than in legislation or regulations.

Another virtue of the Regulatory Reform Policy is that it is very

simple. The entire policy, including definitions, a checklist, an

exemption form, and an example is only seven pages long and written in

very straightforward language (BC’s Regulatory Reform Policy and

Regulatory Criteria Checklist are attached).

Complying

with the Reform Policy involves two important steps. First, the

Regulatory Criteria Checklist must be completed. The checklist has

evolved a bit over time, but it essentially requires ministers to

confirm that any new rules are needed and that they are outcome based,

transparently developed, cost effective, evidence based, and support

BC’s economy and small business. Where these criteria are not considered

or met an explanation must be provided. At the end of the form, there

is a box that asks how many regulatory requirements will be added and

how many will be eliminated, as well as what the net change will be. The

responsible minister or head of the regulatory authority must sign the

form and submit it to the Regulatory Reform Office. In addition, he or

she must make the Regulatory Criteria Checklist available to the public,

at no charge, on request.

When the BC government

first introduced the Reform Policy in 2001, two regulatory requirements

had to be eliminated for every one introduced. At one point, the ratio

was five to one, but today the policy calls for eliminating one

requirement for every new one introduced. That policy expires in 2019.

In

2001, requiring regulators to consider the checklist and eliminate two

regulatory requirements for every new one introduced represented a

dramatic change in thinking about regulation in BC: It put the onus on

the government to make the case that additional regulation was

necessary, to ensure adequate consultation, to keep compliance flexible,

and to reduce the total amount of regulation. One public official

commented that it changed her role from regulation “maker” to regulation

“manager.”

While the new Reform Policy did change the

attitude of those in government over time, there was a lot of initial

internal resistance. However, the decentralized approach to achieving

progress likely helped create buy-in. Not only were ministries tasked

with conducting their own regulatory counts, but each minister was asked

to identify how his or her three-year business plan would meet the

one-third reduction target. When ministry staff realized that they were

in charge of determining changes within their own ministries, the

reforms became easier to embrace. The Deregulation Office was not going

to tell them specifically what to do, but it was there to offer

guidance, support, and feedback from industry about what regulations and

policies were considered especially problematic. In addition, the House

Leader—the person in the legislature responsible for ensuring

government bills become law—had guaranteed that any legislation needed

to reduce regulatory requirements would get on the agenda. This

guarantee proved a powerful incentive for ministry staff who could

sometimes toil away for years on projects that would never see the light

of day.

The three-year timeline proved to be a smart

choice. It created enough urgency around eliminating regulatory

requirements while being enough time to inculcate new habits and

acceptance to the new way of doing things.

Another

feature of the first phase of the reform was an extensive set of

consultations with the private sector. The Red Tape Task Force, largely

made up of industry representatives, was established and tasked with

reviewing and prioritizing 150 different submissions with 600 proposals

for reform from the business community. Each minister was asked to

prepare a three-year deregulation plan outlining how targets would be

met. The minister of deregulation gave the priorities and

recommendations of the Red Tape Reduction Task Force to other ministers

to consider as they prepared these plans.

Some of the

major changes during this period included making significant amendments

to the Workers’ Compensation and Employment Standards Acts in order to

increase flexibility; reviewing more than 3,000 fees and licenses across

government and eliminating, consolidating, or devolving 43 percent of

them; streamlining the Forest Practices Code; and amending mining, oil,

and gas regulations in order to increase flexibility and reduce

administration.

By 2004, BC’s premier and minister of

deregulation had been successful at achieving their stated regulatory

reduction objective. The number of regulatory requirements eliminated at

the end of three years was 37 percent, exceeding the one-third target.

There is no question that political leadership and disciplined

measurement and reporting were critical to achieving this success.

Maintaining Red Tape Reduction: The Middle Years 2004–2013

Between

2004 and 2013, regulatory reform was a lower priority for the

government. Around the time when the one-third reduction target was met,

the minister of deregulation position was eliminated. The Regulatory

Reform Office became part of the Ministry of Small Business and Economic

Development. The minister responsible was enthusiastic about regulatory

reform, but in contrast to the minister of deregulation, he had a long

list of other priorities.

As the deadline for meeting

the one-third reduction target approached, it became clear that the

government had no plans to continue tracking regulatory requirements

beyond 2004. Small businesses were concerned that regulatory creep would

set in unless the regulatory counting continued. Armed with survey

results showing that small businesses wanted government to keep

measuring, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business lobbied the

minister and his colleagues to establish a new target to maintain the

regulatory reduction.

The lobbying effort was

successful and the minister agreed to a target for no net increase in

regulatory requirements through 2008 (a one-in, one-out rule). The

policy of no net increase has subsequently been extended three times—to

2012, to 2015, and, earlier this year, to 2019. Pressure from small

business to keep a target in place has been critical to preserving the

reforms. The target provided a hard-cap constraint on regulators and

meant that measurement had to continue. However, there was not much

political appetite to build on the reforms and go beyond what had

already been achieved.

This period was also

characterized by high turnover of staff in the Regulatory Reform Office,

with none of the original staff remaining. This situation did not prove

difficult in terms of understanding or overseeing regulatory reform, as

the policy is concise and clearly written. However, there were many

small indications that momentum was fading at the bureaucratic level.

For example, the Regulatory Reform Office stopped holding annual

conferences to share best practices, and it did not stay up to date in

publishing its quarterly reports online.

In November

of 2010, a new premier, Christy Clark, was sworn in. Controlling red

tape did not seem to be high on her list of priorities. Regulatory

reform went into maintenance mode with one important exception:

Responsibility for the Regulatory Reform Office went back to the

original architect of the reforms, Kevin Falcon. He helped make the

reforms more permanent by promoting legislation (which passed in 2011)

requiring the government to produce an annual report on regulation that

included measurement. CFIB had been lobbying for this change for a

number of years based on the concern that a future government might undo

the reforms. Legislation requiring annual reporting would make this

harder.

Surviving a Change in Leadership, 2013–present

Premier

Clark’s Liberal Party won the 2013 election with a solid majority. Her

campaign had focused on the importance of balancing the budget, paying

off debt, and developing a liquefied natural gas industry in the

province.

In her first mandate letters to her

ministers, Premier Clark emphasized the importance of minimizing red

tape. She also announced a core review of government services and made

regulatory improvement an important part of the review. This energized

the Regulatory Reform Office, and it has been seriously looking at ideas

for building on, rather than just maintaining, the existing red tape

reforms. As reported above, during the 2015 Red Tape Awareness Week, the

small business minister announced the one-in, one-out policy would be

extended through 2019. More recently, the government passed a law

creating a Red Tape Reduction Day to be held every year on the first

Wednesday in March. The language in the release suggests the government

itself has embraced the importance of an ongoing commitment to reform:

“The new legislation institutionalizes the accountability and

transparency in British Columbia.” The minister responsible also

launched a consultation with British Columbians to solicit new ideas for

cutting red tape, including encouraging people to use the Twitter

hashtag #helpcutredtape to communicate their suggestions.

It

is worth noting that, while BC’s Regulatory Reform Policy is very

broad, it does not cover a few arm’s-length-from-government groups in BC

that have the ability to impose rules on businesses. In some cases,

these groups are clearly creating red tape, and their exemption from

BC’s policy is problematic.

Did Regulatory Reform Make a Difference to British Columbia’s Economic Performance?

There

is no question that BC’s economic performance improved markedly after

2001 in contrast to the “dismal decade” of the 1990s. The province went

from being one of the worst performing in the country to being among the

best. How big a contribution did regulatory reform make to BC’s

economic turnaround? It is hard to answer that question definitively

because regulatory reform was part of a broader package of economic

reforms happening at the same time. For example, when the Liberals came

into office, one of the first things they did was reduce personal income

tax rates across the board by 25 percent, eliminate the provincial

sales tax on production machinery and equipment, and eliminate the

corporate capital tax on nonfinancial institutions.

Despite

the challenge of not being able to quantify the extent to which

regulatory reform contributed to BC’s economic turnaround, it is worth a

brief overview of some of the economic changes. The BC government set

up the British Columbia Progress Board in 2001 to produce benchmark

reports describing the province’s standard of living, job performance,

environmental quality, health outcomes, and social condition relative to

other provinces. Economic indicators from Progress Board reports show

how BC’s position relative to other provinces improved. For example,

economic growth in BC was 1.9 percentage points below the Canadian

average between 1994 and 2001 but 1.1 percentage points above the

Canadian average between 2002 and 2006. BC’s real GDP growth was lower

than Canada’s as a whole in six of the nine years between 1992 and 2000,

but BC’s GDP grew faster than Canada’s every year between 2002 and

2008. Per capita disposable income in BC was C$498 below the national

average in 2000, but by 2006, it was C$60 above the national average,

third behind Alberta and Ontario.

Business creation

also improved. The number of incorporations in BC jumped from 20,759 in

1998 to a high of 34,036 in 2007. The number of incorporations between

2008 and 2013 were a bit lower, ranging from 26,431 to 32,225, but even

the lowest year was higher than any time in the 1990s. The number of

business bankruptcies in BC also decreased considerably over the same

time period, from 1,031 in 1998 to 454 in 2008. The number of business

bankruptcies per year has been falling since 2003 and was only 189 a

year by 2013.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that red

tape reduction was an important contributor to British Columbia’s

recovery. For example, mining is a historically important industry in BC

that was in decline in the 1990s, but it rebounded after 2000.

According to a task force on mining established by the government in

2008, “The provincial government has taken many important

steps—improving its tax competitiveness, streamlining regulatory

requirements and investing in the province’s geosciences mineral data

collection and analysis—to enhance BC’s reputation as an important

mining jurisdiction and industry has responded with record exploration

levels and the opening of new mines in the recent period of economic

growth.” This statement is typical of the kinds of statements coming

from industry at a time when tax and regulatory competitiveness are

highlighted as key to the provincial economic turnaround.

Lessons from the BC Model for US Governments Interested in Red Tape Reduction

The

United States and Canada share more similarities than differences in

overall economic conditions and general cultural attitudes, which makes

Canada’s experience with red tape reduction and control relevant to the

United States. US governments at the state and federal level will find

much to borrow from and some things to improve upon in the lessons from

British Columbia.

Lesson #1: Language Matters

BC’s

reforms were born in the context of “hitting the wall” with

uncompetitive taxes and excessive regulation. This situation created a

climate where the general public supported making cutting regulation a

clear priority. A poorly performing economy initially allowed for the

more aggressive “deregulation.” Once the economy improved, the context

changed and “regulatory reform” was more acceptable to the public. More

recently, a senior minister commented how helpful it was to make a

distinction between red tape and necessary regulation. Indeed, it is

much harder to argue against cutting red tape, a problem most can relate

to in some way, than it is to argue against regulatory reform, which

can be confused with cutting justified regulations. The language used in

BC today is better at maintaining public support for cutting red tape,

and it would likely have been as effective, if not more effective, than

the “deregulation” language used at the beginning of the reforms. Indeed

much of the “regulation” that was cut (such as restaurants being told

what size televisions they could have in their establishments) was

clearly red tape.

Lesson #2: Political Leadership Matters

Regulatory

reform in BC has been successful because it has had strong political

champions. Leadership from the top was critical to the success of the

reforms. However, it was also important in the early years to have other

strong political leaders who could lead the execution of the reforms.

In BC’s case this initially came from the minister of deregulation,

whose sole responsibility was to focus on effectively implementing the

reforms.

For regulatory reform to be successful, it

must have broad buy-in from politicians and from civil servants. The

buy-in in BC was the result of strong political leadership from the top,

a decentralized approach to reform where ministries could chose the

regulatory requirements to cut, and a three-year timeline, which created

urgency while still allowing time to adapt to the change.

Lesson #3: A Clear, Credible, Simple Measure Matters

One

thing that distinguishes BC’s regulation reforms is the clear metric

that was used to establish whether the reforms were successful. BC’s

measure has several virtues: it is clear, fairly comprehensive, and easy

to update. There is no perfect way to measure the broad burden of

regulation, and there are certainly alternative approaches to the

regulatory requirement metric used in BC that would be just as good, if

not better. However, too often, regulatory measures become so complex

that they are too expensive for governments to consider adapting, and it

is not at all clear that the additional complexity delivers more

accuracy or better results. A simple measure has the added advantage of

being easy to communicate to the public.

Lesson #4: A Hard-Cap Constraint on Regulators Matters

At

the federal and state levels in both Canada and the United States,

regulatory impact analysis has been used as a “check” on regulators.

RIAs may slow down the growth of regulatory activity, but available

evidence suggests that they do not stop it. BC’s target of reducing

regulation requirements by one-third in three years and then maintaining

the reduction has set a hard cap on the total amount of regulatory

requirements. This has forced a discipline that did not previously

exist, a discipline that has helped change the culture within government

to one where regulators see their job as focusing on the most important

rules.

One of the challenges for governments

interested in reducing, rather than just controlling, red tape is

picking a reduction target. BC’s choice of a one-third reduction target

was not scientific. However, the political “gut feeling” was that a

one-third target would be achievable without compromising justified

regulation. The choice seems to have been reasonable, as there is little

evidence that the regulatory reduction in the province compromised

health, safety, or environmental outcomes. Interestingly, on the CFIB

survey, small business owners in both Canada and the United States also

suggest that about a one-third reduction in rules is possible without

compromising the legitimate objectives of regulation (see figure 1).

As

was mentioned at the beginning of this paper, the Canadian government

recently adapted BC’s one-in, one-out policy, becoming the first country

in the world to legislate a hard cap on regulations. The legislation is

new, but it has been the policy of the government for the past several

years. As of December 2013, the rule had achieved a net reduction of 19

regulations, saving business 98,000 hours and $20 million. While this

reduction is small in the grand scheme of the costs of the overall

regulatory burden, it is nonetheless a quantifiable reduction and

another indication that hard caps matter.

Lesson #5: Institutionalizing Red Tape Control Matters

Perhaps

one of the most remarkable things about the BC model is its longevity.

An important transition happened once the initial one-third reduction

target was met: a new target for zero net increase in regulatory

requirements was set. The government has extended this commitment

several times and ensured that measuring red tape requirements has

continued. While it is impossible to say with certainty that there would

have been more red tape without the controls, it is clear that there

would have been less transparency and less ability to evaluate the broad

regulatory burden without the ongoing measure, which provides a

benchmark.

In contrast, Nova Scotia’s government

implemented its own red tape initiative, which had some initial success,

but it was not followed by institutional commitment. Several years

after BC launched its reforms, the Nova Scotia government was convinced

of the merits of setting and measuring targets. In 2005, Nova Scotia set

a target for a 20 percent reduction by 2010 in the time business owners

spend on regulation. The starting benchmark was 613,000 hours, and the

government successfully achieved its goal. It then stopped measuring and

there is currently no way to know whether the time spent by businesses

complying with rules has increased, decreased, or stayed the same. A

recent report commissioned by the Nova Scotia government strongly

recommends that the government find effective ways to eliminate red

tape, including reestablishing measurement and “creating mechanisms,

including legislation, to sustain the regulatory modernization agenda

over the long term.”

Final Lesson: Outside Advocacy Can Make All the Difference

Regulation

is largely a hidden tax that most directly affects business owners, in

particular small business owners. Having the support of organizations

that represent small businesses has been very important in keeping the

BC government committed to its reforms and in encouraging other

governments in Canada, including the federal government, to follow the

example set by BC. In fact, without the advocacy coming from small

business, it is doubtful that BC’s reforms would still be in place

today. Several effective steps that the CFIB took in pushing to continue

reforms include the following:

- Regularly meeting with politicians from the governing party and opposition parties to present survey results from small businesses that showed why it was important to continue the reforms. These meetings helped make red tape reduction a nonpartisan issue that all parties could support. This strategy worked at the federal level too.

- Issuing an annual report card on governments across Canada. BC was the only jurisdiction to get an A and wanted to keep it.

- Holding an annual “Red Tape Awareness Week,” which keeps a spotlight on the issue and gives politicians credit and publicity for making announcements about cutting red tape.

- Publishing research reports estimating the costs of the broad regulatory burden and red tape.

- Connecting business owners with media during Red Tape Awareness Week so that the public could get a better understanding of the costs and frustration of red tape.

- Issuing an annual “Golden Scissors” award for cutting red tape. Kevin Falcon, the BC minister responsible for the initial reforms, was the first to receive the award.

Conclusion

As

average incomes in countries like Canada and the United States have

increased, the demands for better health, safety, and environmental

provisions have also increased. Available evidence, while limited,

suggests that at least some of these demands have been expressed in an

increase in the number of mandatory rules our governments issue. It

seems reasonable to assume that some of the increase in the broad

regulatory burden is justified regulation and some is red tape.

The

challenge for modern governments is to control the growth of red tape

in the messy real world, where measures are imperfect and the line

between justified regulation and red tape can be difficult to establish.

The BC model of red tape reduction stands out for its simplicity,

effectiveness, and longevity. Not only did the BC government accomplish

its goal of reducing the number of regulatory requirements by more than

one-third in three years, it has maintained the reduction for over a

decade. Its approach, which is very different from what other

governments have tried, uses essential ingredients that are really just

common sense: measurement, a cap on the total burden of regulation, and

political leadership. A blueprint for common sense regulatory reform is

long overdue, and I hope it proves useful to US governments interested

in improving the welfare of their citizens. Reducing red tape has the

power to unleash entrepreneurship and make us all better off.

No comments:

Post a Comment