Extreme Shipping: When Express Delivery to California Meant 100 Grueling Days at Sea

—

June 2nd, 2016

At the frenzied height of our current technological

gold rush, the denizens of America’s West Coast cities can have almost

anything delivered within 24 hours—food, toilet paper, shoes, marijuana,

and so on. But during California’s first boom, it typically took more

than 100 days for goods or people to reach San Francisco from the East

Coast. Getting there at all was a death-defying feat.

“It sounds romantic, but I think it was a rather miserable existence for everyone.”These harrowing oceanic journeys around South America’s Cape Horn were made by the famous clipper ships, named because they moved at such a fast clip, at a time when there was no quick route over land. Today, in modern San Francisco, the land of disjointed public-transit systems, riders are encouraged to purchase a Clipper Card (emblazoned with an abstracted ship in full sail), which offers holders a slightly speedier ride via smoother transfers and lower fares. It’s anyone’s guess how long these plastic cards will remain in use, but the original clipper ship era was short-lived, lasting roughly from the late 1840s through the 1860s. Still, the ships became legendary because their dangerous voyages thrust the West Coast into the future: Clipper ships delivered essential goods needed to build the region’s new cities and railroads, while their advertising campaigns were fortuitously timed to take advantage of new developments in full-color printing.

Author and researcher Bruce Roberts explores the evolution of advertising for clipper ship journeys in his 2007 book, Clipper Ship Sailing Cards. Using these advertising cards as his entry point—think of them as postcard-sized fliers, the popup ads of their day—Roberts opens a window into a fascinating period in the history of transportation, printing technology, and graphic design.

In his book, Roberts explains that the clipper ships’ forebears date to the War of 1812, when the U.S. government hired privateers, or privately owned ships, to assist their attacks on the British navy. These vessels were mostly schooners and brigantines, which were small, speedy, and easy to maneuver, making them very effective against England’s fleet of well-armed but larger and slower ships.

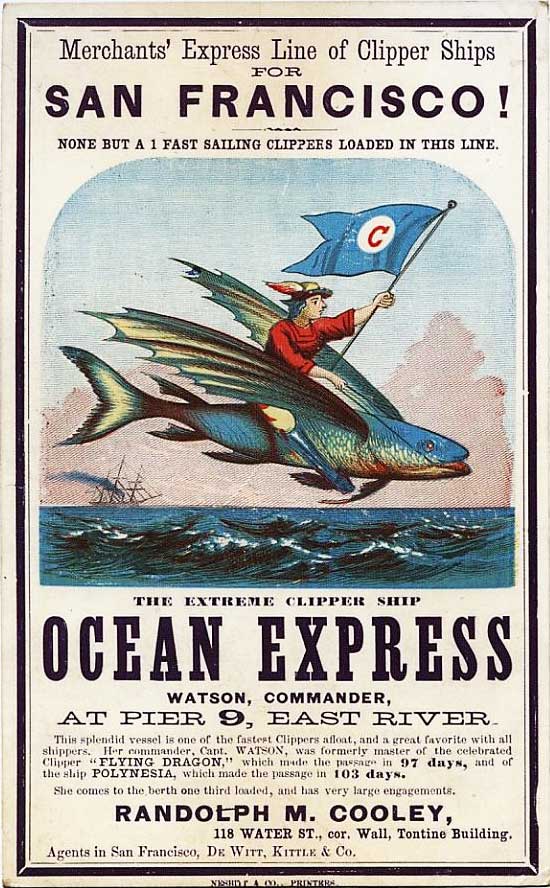

Top:

A flying fish conveys the skillful skippering of the Ocean Express,

circa 1862. Above: Two cards for the Witchcraft rely on similar imagery,

at left, 1855, and right, late 1858. Courtesy Wikimedia and the MIT

Libraries.

Because designs continued to evolve, Roberts says there’s no agreement on which was the very first clipper ship. Upon its completion in 1845, the Rainbow became the first ship built with a concave or inward-curving bow, which would soon become essential to the clipper design. The following year, a ship called the Sea Witch upped the ante with its additional sparring (the horizontal yards attached a ship’s mast and used to hold rigging), as the extra sails increased its potential speeds. Roberts points to the Sea Witch’s voyage to China in December of 1846 as the launch of the clipper ship era, as it heralded a period of booming trade and decreasing transit times.

This

card for the Franklin linked the ship with various technological

achievements, including the iconic Benjamin Franklin and his kite, circa

1860s. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

These vessels were often bedecked with six or seven sails per mast. “Shipbuilders were like, ‘You know what? People would spend their last dollar to get there, so we’ll build ships with less storage capacity, but boy, these little things will get there pretty quickly,’” Roberts explains. “Of course, ‘pretty quickly’ was still close to four months of travel. It sounds romantic, braving the waves and forging ahead on these sailing ships, but I think it was a rather miserable existence for everyone.”

In the United States, the most common clipper route was from New York or Boston to San Francisco, all the way around Cape Horn at the southernmost tip of South America. Once a clipper had unloaded its cargo in California, the crew might turn around and head back to the East Coast empty, or maybe on to a major Chinese port like Shanghai. “You can see how the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 made life easier for everyone,” Roberts says. “Even before that, you had an alternate route, which was miserable in its own special way: You could cross the isthmus by land, and then hopefully catch a steamer that was going up from there to San Francisco. But the crossing wasn’t great—there were mosquitoes, malaria, and cholera—so you might be crazy when you were done with that route, too.”

Clipper voyages were initially advertised via newspapers, but due to printing conventions, these ads weren’t very visually enticing. “Newspapers of the time had very narrow columns and the text was tiny,” Roberts says. “There were lots of oddball listings, and nothing really jumped out. Yesterday, I was looking at some newspapers from 1865 announcing the assassination of President Lincoln, and even then, you had maybe six or eight columns of itsy-bitsy text, and in about column 4 or 5, there’s the headline: ‘Great calamity—President assassinated.’ It’s like, ‘Whoa!’ If you weren’t looking closely, you might’ve missed it.”

A

card for the Dreadnought, named after a series of famous warships,

printed by George Nesbitt & Co. in 1865. Courtesy Bruce Roberts.

By the late 1850s, clipper voyages were increasingly marketed with specialized advertising cards—sometimes called clipper ship cards, sailing cards, shipping cards, or clipper cards—urging customers to contact a specific ship’s agent if they needed goods sent west. “Advertising cards go back to at least the 1700s, but the earliest were very plain,” Roberts says. “Printing technology made amazing strides in the 1840s and ’50s, and clipper ship cards were a kind of prelude to more widely distributed trade cards, popular in the 1870s and ’80s.”

Barely larger than modern postcards, clipper ship cards were generally printed a few weeks before a ship’s planned departure date, then sent to local merchants and posted publicly to entice potential customers. “Just about anything you could think of was being shipped—food products, tools, building materials,” Roberts says. “Clippers were also carrying lots of components to build railroads in California.” Ultimately, once these rails stretched clear across the western United States, their freight capacity would contribute to the clipper industry’s downfall.

Left,

a card advertising the Pharos printed by Watson’s Press in Boston

around 1869, with its chromolithography layers seen at right. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society. (Click to enlarge)

“For the most part, when clipper cards were issued, it meant there was still some space on a particular ship its owners hoped to fill,” he continues. “You’ll see cards that say, ‘This ship is rapidly loading at Pier 16,’ but that clipper probably wasn’t filling up at all, which was why they were advertising.”

Although many publishers made cards for clipper companies, the market was dominated by two printers, George Watson in Boston and George Nesbitt in New York City. By contrast, clipper cards printed in San Francisco to advertise the return trip to Boston or New York, of which very few survive, were turned out by a wide variety of single-job printers. “Nesbitt wound up controlling around 98 percent of the clipper card market in New York,” Roberts says. “He was a well-established printer who made all sorts of things—in fact, his firm produced the first postage-stamped envelopes. I’ve documented many printers, and none had a clipper-card output anywhere near the quantity of Nesbitt—and nowhere near the quality, either.”

Left,

a Nesbitt card from 1865 advertising the Seminole. Right, a Watson

design for the Robin Hood, also from 1865. Courtesy Bruce Roberts.

Clipper ship cards sometimes included evocative imagery to help potential customers remember the name of a particular ship, like the witch-on-a-broom advertising of a “well-known and favorite” ship called the Witchcraft. “More often than not,” Roberts says, “a clipper card for a ship bearing a woman’s name will picture a woman, although not necessarily a likeness of its namesake. But the imagery was all over the place. The same image might be used to advertise different voyages of the same ship, or different ships altogether. I think it was more a matter of what the printer could come up with, or had on hand. ”

This

1859 Great Republic card is a rare double-sided design with patriotic

imagery, including the seals of 33 states, on the front (left) and

textual information on the back (right). Courtesy Bruce Roberts.

For cards that lacked eye-catching illustrations, a ship’s name was one of its few selling points. Heavy-handed references to strength, bravery, and speed were conveyed with ship names like the William Tell, Florence Nightingale, Robin Hood, Pocahontas, Andrew Jackson, Ocean Express, Hornet, Sea Serpent, Comet, Good Hope, Defender, Invincible, Conquest, Shooting Star, Cyclone, and Eagle Wing. (Car manufacturers still rely on this type of associative branding, with models like Jeep’s Cherokee or Ford’s Explorer, or entire companies named after luminaries like Tesla.)

“There was one ship called the Flying Cloud that twice made the trip from New York to San Francisco in the record time of 89 days plus a few hours,” Roberts says. “But if you look at enough clipper cards, you’ll see the vessels are often advertised as the ‘fastest ship in the world.’ Not true.”

Along with an economic depression known as the Panic of 1857, the American Civil War hastened the clipper industry’s undoing, as Confederates destroyed hundreds of vessels headed from northeastern ports to the West Coast. Eventually, after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, oceanic transport would be supplanted by trains as they cut coast-to-coast travel times to less than a week. But Roberts believes the real culprit was steamship technology, as these larger-capacity ships offered a cheaper way to send freight by sea. “Steamships could always hold more cargo than a clipper could,” Roberts says, “and over time, their engines became stronger and more reliable.”

Indeed, the clipper ship’s main weakness had always been its dependence on the weather, which meant that even the best-designed ships were stuck if the wind died down. “They’d just have to bob around for awhile,” Roberts says. “That wasn’t a problem for steamships. There were plenty of times when a clipper was making great time, but then they’d get near Cape Horn, storms would come up, and they’d get thrown onto the shore, or worse. Many never made it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment