Pilgrim fathers: harsh truths amid the Mayflower myths of nationhood

As Plymouth marks 400 years since the colonists set sail, the high price paid by Native American tribes is now revealed in an exhibition

For a ship that would sail into the pages of history, the Mayflower was not important enough to be registered in the port book of Plymouth in 1620. Pages from September of that year bear no trace of the vessel, because it was only only 102 passengers and not cargo, making it of no official interest.

The port book is one of the many surprising objects at Mayflower 400: Legend & Legacy, the inaugural exhibition of the Box in Plymouth, Devon, which will open to the public later this month, and which is part of the city’s efforts to mark the 400th anniversary of the ship’s Atlantic crossing.

“This wasn’t a huge historic voyage in 1620. If anything, it was an act of madness because they were going at the wrong time of year into an incredibly dangerous Atlantic,” said the exhibition’s curator, Jo Loosemore.

The omission in the port book is one of many gaps surrounding the voyage of the Mayflower that the exhibition tries to fill. The general story is well known: the Mayflower took its 102 men, women, and children – the majority of whom were Puritan religious dissenters known as Separatists, but also called Pilgrims – from Plymouth to what they hoped would be the Hudson river. They endured a treacherous 66-day voyage and were blown off course, landing on the tip of what is now Massachusetts, before crossing the bay to set up a colony on land belonging to the Wampanoag, whose name means “people of the first light” and who had inhabited the area for some 12,000 years.

They had an estimated population of at least 15,000 in the early 1600s, and lived in villages on the Massachusetts coast and inland. Their help enabled the English to survive, and also became the basis for the much-mythologised first Thanksgiving feast, still celebrated in the US as a national holiday, though not without controversy. The reality, as this exhibition shows, was far more complicated – and violent.

Although the Pilgrims are often used as an origin myth for the US, the English were late arrivals to North America. Juan Ponce de León explored Florida as early as 1513, and the Spanish had a settlement in St Augustine by 1565, while French Huguenots tried and failed to establish a colony on the coast of what is now South Carolina in 1562.

Some 35 years before the Mayflower, two ships set sail from Plymouth to explore the North Carolina coast, and the following year the colony of Roanoke was established, but by 1590 all the settlers had disappeared. Eventually, in 1607, the English had success with the colony of Jamestown, Virginia, which managed to survive. As well as these early settlers, Europeans came to trade – and often to kidnap and enslave Native Americans – well before the arrival of the Pilgrims.

Part of the exhibition looks at these failed attempts at colonisation. “People living and working in Plymouth might be surprised about the importance that the city has played in that part of history,” said Nicola Moyle, head of heritage, art and film for the Box. “There were the Mayflower passengers, but more importantly the institutions that have roots in Plymouth that were playing a part in encouraging settlements taking place on the eastern part of the US.”

This was also the case for the Separatists. Although the mythology presents them as fierce critics of the Church of England seeking religious freedom, they had already found that in the Dutch city of Leiden, where they lived for a decade before crossing the Atlantic. What drove them onwards was the lack of economic opportunity.

“It’s just not the story we think it is,” said Loosemore. Economic factors fuelled the Separatists’ decision to obtain permission from the London Company of Virginia to establish a colony, and for funding from the Company of Merchant Adventurers.

But religious freedom and economic opportunity for the English would come at a heavy price for the Wampanoag. By the time the English arrived, the Wampanoag would have been familiar with Europeans, including the terrible diseases they brought. A few years before the Mayflower’s passengers landed, a plague wiped out an estimated 70% of their population. When the Pilgrims stepped ashore, the Wampanoag had been significantly weakened and were willing to make alliances with the English in order to keep their rivals, the Narragansett, at bay.

Although there were periods of good relations between the English and Wampanoag, there were also violent conflicts, culminating in King Philip’s War of 1675, which ended with the head of Metacom, the Wampanoag leader, being put on a spike and the survivors sold into slavery. It was a far cry from the scenes of a harvest celebration.

“These were people who came here for their religious freedom because they couldn’t worship as they pleased in their own country, and yet when they came to this country they did not seem to have that same tolerance for the people that they met here, despite all that the Wampanoag did to help them,” said Paula Peters, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Nation and of the advisory council to the exhibition. “You can’t have a colony without someone being colonised.”

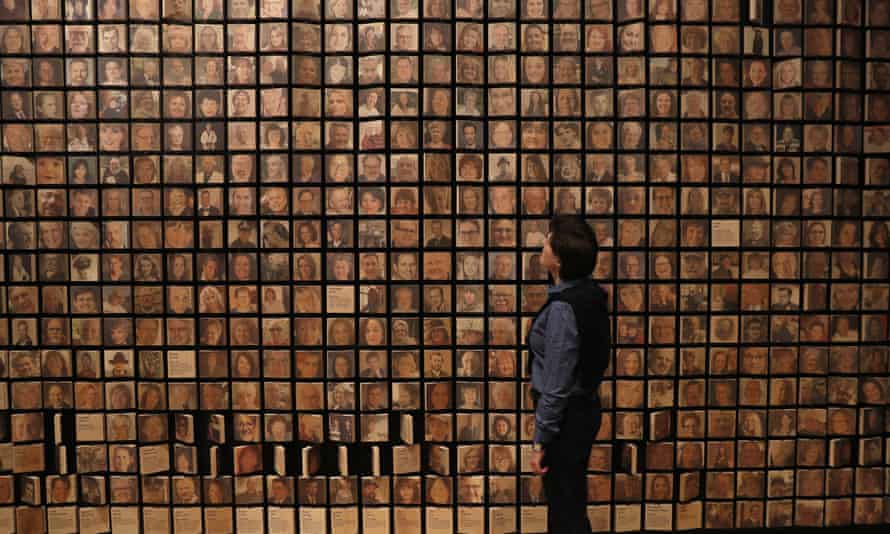

The Wampanoag objects included in the show – some of which have never been seen outside the US – give a sense of both how they lived before the English arrived and after. One key piece is a commissioned pot by Wampanoag artist Ramona Peters, also known as Nosapocket, that draws from the group’s tradition. There is also a national touring exhibition of a new Wampum belt made of shell beads that will stop at the Box later this year.

Elsewhere in the exhibition is what is considered to be the first Bible printed in North America. Published in 1661, it is in the version of the Algonquian language that the Wampanoag spoke. It is known as the Eliot Indian Bible, named after chief evangelist John Eliot, who set up a series of “praying towns” to promote the conversion of the Native Americans to Christianity.

Yet the myth of Native American and English in Thanksgiving harmony remains, and these cheerful commemorations are the focus of the final part of the exhibition. There are display cases with Mayflower-related goods: plates and mugs, biscuit tins, stamps and tea towels. This mythology persists, despite the fact that the Pilgrims were not the first Europeans to arrive in North America, and their relationship with the Wampanoag was far from peaceful.

To Loosemore, the key to understanding this larger story lies in the rediscovery of a manuscript describing the Pilgrims’ experiences in the Netherlands and new world. Of Plymouth Plantation was written by the colony’s leader, William Bradford, 20 years after his arrival, but the manuscript was lost until 1855, when it surfaced in the collection of the bishop of London. “Its rediscovery has a lot to answer for in the sense that it inspired this Victorian interest in the Mayflower,” said Loosemore.

Around the same time, in the US, President Abraham Lincoln declared a Thanksgiving holiday in 1863 in an attempt at national unity while the civil war was under way. In the decades that followed, these strands merged together into a narrative, which was fostered by a New England elite that including many prominent US leaders who were Mayflower descendants, such as the second president, John Adams, whose letters are on display in the show.

Jamestown, with its slavery, and St Augustine, with its Spanish Catholics, were ignored, and the national story became that of the hard-working, freedom-seeking Protestant “Pilgrim fathers”, aided by kind Native Americans. Now, says Peters, there is a chance for the public to learn a different story.

“For me, it’s an opportunity to say, yes, we are still here, and what happened to us mattered.”

No comments:

Post a Comment