Fracking: A Look Back

December 2012

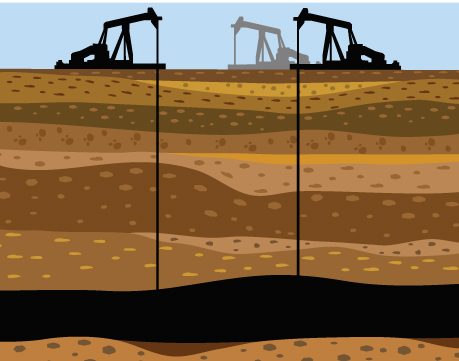

In the midst of a modern boom in U.S. petroleum production, hydraulic fracturing is now done on a massive scale with new methods that put once-inaccessible oil and gas within reach. Those new methods are fueling a fractious public environmental debate.

High-pressure fracking and new methods of horizontal well drilling are making it possible for producers to tap vast new plays of natural gas and oil trapped in tight sand and shale formations. The biggest, North Dakota’s Bakken Play is producing a new generation of oil millionaires in a region long stuck in economic obsolescence.

By some estimates, up to 90% of today’s producing wells were stimulated by fracking. That’s cause for concern among environmentalists who tie recent reports of groundwater contamination in high-fracking areas to the high-pressure injection of toxic fracking chemicals to depths of several thousand feet. So far, official studies have not proven that link but the debate continues.

Explosive Origins

The mechanical principles of fracking have not changed since the first brave shooter dropped an explosive charge down a well in the 1860s. Then as now, the task is to deliver a powerful force to a designated depth underground, rubblizing the hard rock formations around the well to stimulate the release oil or gas trapped within. Modern methods use high-pressure jets of water, chemicals, and sand to break up formations. Acting as a proppant the sand seeps into the resulting cracks and keeps them open. Oil and gas permeate the sand en route to the well casing.

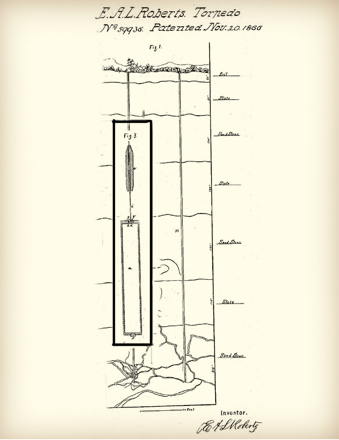

Diagram of Lt. Col. Edward A. Robert’s “exploding torpedo”.

Inspired by the Civil War veteran’s observations of damage from artillery shelling on the battlefield, the torpedo was an iron shell packed with 15 to 20 pounds of gunpowder and topped off with an explosive cap. Shooters lowered it cautiously down the bore hole to the desired depth, and then dropped a weight down the well where it detonated the cap. Roberts pumped large amounts of water down the well to achieve what he called “superincumbent fluid tamping” to concentrate the power of the explosion as it sent cracks through the formations below.

As the contact explosive nitroglycerin began to find favor over powder, fracking grew even more dangerous. Whatever safety advantages nitro might have had over gunpowder in the presence of sparks or flames could be erased with one slip of the hand. “The chap who struck it a hard rap might as well avoid trouble among his heirs by having had his will written and a cigar-box ordered to hold such fragments as his weeping relatives could pick from the surrounding district,” wrote John J. McLauren in an 1869 chronicle of spectacular oilfield accidents.

Risks aside, when reports of 1,200 percent production increases began to circulate, the embryonic petroleum industry took note of the Roberts Torpedo and his company flourished. He was able to command not only a handsome price for his torpedos but also a royalty based on a well’s increased productivity. He reinvested a considerable chunk of his fortune into defending his patents from operators who took to fracking under cover of night to avoid Roberts’ royalties. One explanation for the origins of the term “moonlighting” comes from this rogue practice.

Commercial Fracking Explodes

According to a 2010 fracking history by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), the idea of non-explosive alternatives to nitroglycerin took root in the 1930s. Experiments through the next decade paved the way for the first industrial-scale commercial uses of the modern patented “Hydrafrac” process in1949, with Halliburton holding an exclusive license in the early years. SPE recounts that 332 wells were fracked in the first year alone, with up to 75 percent production increases recorded. By the mid-1950s, fracking hit a pace of about 3,000 wells a month.A typical early fracture took 750 gallons of fluid (water, gelled crude oil, or gelled kerosene) and 400 lbm of sand. By contrast, modern methods can use up to 8 million gallons of water and 75,000 to 320,000 pounds of sand. Fracking fluids can take the form of foams, gels, or slickwater combinations and often include benzene, hydrochloric acid, friction reducers, guar gum, biocides, and diesel fuel. Likewise, the hydraulic horsepower (hhp) needed to pump fracking material has risen from an average of about 75 hhp in the early days to an average of more than 1,500 hhp today, with big jobs requiring more than 10,000 hhp.

Fracking’s new golden age began in 2003, as oil and gas producers began to explore the nation’s massive shale formations in earnest. Today companies are extracting more oil and gas from the Bakken than they can ship.

Fracking Fracas

For those concerned about U.S. dependency on foreign oil or about the still-hobbling economy, the modern-day oil boom is heartening. But not everybody is happy. Environmentalists, local citizen groups and more than a few celebrity supporters are calling for more independent study of potential risks and more regulation. Their concerns are heightened by a lack of state-to-state uniformity in chemical disclosure requirements. Those concerns were aggravated in 2005 when fracking was specifically exempted from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act.As the public works to sort out these issues, engineers will no doubt be part of the team that eventually strikes it rich in the hunt for a technological compromise.

No comments:

Post a Comment