There Is No ‘Epidemic of Mass School Shootings’

It’s

been two weeks since a heavily armed psychopath turned Marjory Stoneman

Douglas High School into a war zone — and the survivors of that

massacre have already changed gun politics in the United States for the better.

With

their acts of witness and advocacy, the teenage protesters of Parkland,

Florida, shook many voters out of their complacency about pervasive gun

violence. Upwards of 30,000 people lose their lives to firearms in our

nation each year, a level of carnage unparalleled anywhere in the

developed world. And yet, last October — just days after the worst mass

shooting in American history — only 52 percent of Americans told CNN’s pollsters that they supported “stricter gun laws.”

Today, that figure is 70 percent — the highest it’s been at any time since 1993. Recent polls from Quinnipiac University and Politico/Morning Consult

have produced nearly identical results. In Florida, long a bastion of

NRA support, the leftward turn in public opinion has been especially

sharp.

Moderate Democrats have had their “come to an assault weapons ban” moment. Moderate Republicans (such as they are) are imploring their party to move left on the gun issue. Major gun sellers are cutting ties with the NRA and imposing their own restrictions on firearm sales. Even Donald Trump has called for strengthening America’s background check system.

By

keeping the national spotlight on the mass murder at their high school —

and calling on their peers across the country to walk out of their

schools, so as to “no longer risk their lives waiting for someone else to take action to stop the epidemic of mass school shootings” in

the United States — the theater kids of Marjory Stoneman Douglas have

built the broadest public consensus for gun-safety measures that

America has seen in a quarter-century.

But

they’ve also (inadvertently) triggered a moral panic about the safety

of America’s schools that has little basis in empirical reality — and

which is already lending momentum to policies that would increase juvenile incarceration, waste precious educational resources on security theater, and bring more guns into our nation’s classrooms.

On Tuesday in Tallahassee, Republicans in Florida’s state legislature advanced a law

that aims to put one police officer — and ten gun-wielding teachers —

into every public school in the state. The $67 million “school marshal”

program would provide teachers who volunteer to be emergency gunslingers

with a $500 stipend, a background check, drug test, psychological exam,

and 132 hours of training. In total, the bill’s school safety measures

come at a price tag of $400 million. One piece of that package — an

increase in funding for mental health counselors — is laudable. The rest

are either unnecessary or actively dangerous. The average salary for a

teacher in Florida is nearly $10,000 less than the national mean; its

public school system consistently ranks among the bottom half of U.S.

states. This is not a place that can afford to misallocate hundreds of

millions of dollars in educational funds.

The

bill moving through Florida’s House of Representatives does pair that

$400 million appropriation with a few gun reforms — a three-day waiting

period for firearm purchases, an increase in the legal age for

gun-buying from 18 to 21, and measures expanding the authority of police

officers to confiscate guns from people who threaten to commit

violence.

By

themselves, those reforms are better than nothing. And the fact that

Republican state legislators are pushing them forward — over the

objections of the NRA — is a testament to the power of the Parkland

protesters. But the impact of such modest regulations of the gun market,

in a nation where firearms outnumber people, is likely to be marginal

at best. And if the bill’s gun reforms cannot be separated from its

“school marshal” program and expansion of classroom cops, then Florida’s

young people might end up worse off than they’d be if their elected

leaders had simply ignored the Parkland massacre, like so many mass

shootings before it.

After

the atrocity at Columbine High School in 1999, America tested the

hypothesis that a massive increase in school policing would lead to

lower rates of violence on campus — in 1997, 10 percent of public

schools employed at least one police officer; by 2014, 30 percent did. The results of this experiment have been worse than disappointing. The best available research

suggests that putting police officers in schools does not significantly

deter crime — but does increase the number of students who end up

incarcerated for minor youthful indiscretions (and/or, who get electrocuted with stun guns in their classrooms for the same).

Arming

teachers, meanwhile, is a proposal so mind-bogglingly dumb and

dangerous, even Florida’s GOP governor Rick Scott rejects it. There is

no evidence whatsoever that adding a not-so-well regulated militia of

amateur marksmen to every school faculty will prevent mass shootings,

when armed guards have consistently failed to do so — but there is good

reason to believe that such a program would radically worsen our

nation’s preexisting crisis of racially discriminatory,

teacher-on-student violence. As Patrick Blanchfield argues for the Intercept:

In 2017, researchers estimated that, in a given school year, 589 children are corporally punished (most often struck with paddles) every day. Unsurprisingly, this violent discipline is disproportionately inflicted on students of color. Black students are twice as likely as whites to be struck in Georgia, North Carolina, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. In Maine, black children are eight times more likely to be hit than white children are. Children with disabilities also suffer a disproportionate share of this disciplinary violence. In a representative year, school authorities pinned down, tied up, or otherwise restrained 267,000 American schoolchildren, three-quarters of whom had some kind of disability; such practices have resulted in multiple fatalities.

… America already has abundant and grim evidence about the outcomes of interactions between youth and armed authority figures. The lethality of our police has no real analog in the developed world: One-third of all Americans killed by strangers are killed by police. Here, too, the landscape of violence betrays stark disparities, particularly when it comes to children: Black teens are 21 times more likely to be shot dead than their white peers, and people with disabilities and mental illnesses are acutely vulnerable as well…Why would we expect different outcomes from arming teachers?

If

the policy response to the Parkland shooting ends up hurting more

American students than it helps, the lion’s share of responsibility will

lie with the Republican Party. The Parkland survivors have been as

emphatic in their rejection of arming teachers as they’ve been in their

support for gun restrictions — and they’ve won the general public to

their side of both issues.

But

some of the hyperbolic rhetoric that progressives have embraced over

the past two weeks has made it easier for the right to push regressive

school safety policies. Such hyperbole pervades the mission statement for the post-Parkland protest movement, March for Our Lives:

Not one more. We cannot allow one more child to be shot at school. We cannot allow one more teacher to make a choice to jump in front of a firing assault rifle to save the lives of students. We cannot allow one more family to wait for a call or text that never comes. Our schools are unsafe. Our children and teachers are dying. We must make it our top priority to save these lives.

March For Our Lives is created by, inspired by, and led by students across the country who will no longer risk their lives waiting for someone else to take action to stop the epidemic of mass school shootings that has become all too familiar.

… School safety is not a political issue. There cannot be two sides to doing everything in our power to ensure the lives and futures of children who are at risk of dying when they should be learning, playing, and growing … Every kid in this country now goes to school wondering if this day might be their last. We live in fear.

American

children do not “risk their lives” when they show up to school each

morning — or at least, not nearly as much as they do whenever they ride

in a car, swim in a pool, or put food in their mouths (an American’s lifetime odds of

dying in a mass shooting committed in any location is 1 in 11,125; of

dying in a car accident is 1 and 491; of drowning is 1 in 1,133; and of

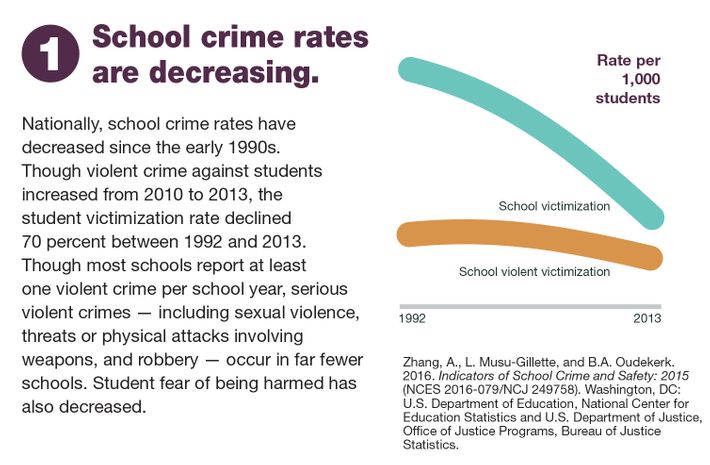

choking on food is 1 in 3,461). Criminal victimization in American

schools has collapsed in tandem with the overall crime rate, leaving U.S. classrooms safer today than at any time in recent memory.

And,

perhaps most critically, there is no epidemic of mass shootings in

American schools — at least, not under the conventional definitions of

those terms.

In

the immediate aftermath of the Parkland shooting, progressive activists

and commentators (including this one) repeatedly claimed that there had

been 18 school shootings since the start of this year. This proved to

be a gross exaggeration. In reality, according to new research from Northeastern University,

there have been a grand total of eight mass shootings (shootings that

kill at least four people) at K-through-12 schools in the United States

since 1996. Meanwhile, over the past 20 years, the number of fatal

shootings in American schools (of any kind) has plummeted.

If

mass school shootings were the only form of gun violence in the United

States, the case for treating the regulation of firearms as a pressing

policy issue would actually be fairly weak. For the past

quarter-century, there has been an average of one mass murder (a killing

of four or more people committed with any weapon, as opposed to just

firearms) in an American school each year. Every one of those atrocities

is a blight on humanity. But it is nearly impossible to design a policy

that can bring the incidence of an already exceptionally rare crime

down to zero — and given the inherently limited nature of legislative

time and resources, it would make little sense to prioritize such a

marginal and difficult issue over public health challenges that kill

exponentially more people.

There

is no “school safety” crisis in the U.S.; only a gun violence epidemic

that consists primarily of suicides, accidents, and single-victim

homicides committed with handguns. In the decades since Columbine,

progressives have often led the public to believe otherwise. And for

understandable reasons. Spectacular acts of mass murder committed

against children (especially upper-middle class children in “good”

public schools) attract a degree of media attention and political

concern that our nation’s (roughly) 20,000 annual firearm suicides — and

daily acts of urban gang violence — simply do not. The most misleading

piece of the Parkland survivors’ message — that their experience is

representative of a widespread social problem that threatens the lives

of all American children — may well be its most politically effective

component.

But

if misrepresenting the nature of America’s gun problem has political

benefits, it also has policy drawbacks. After all, if the March for Our

Lives mission statement were actually true — if “every kid in this

country” went “to school wondering if this day might be their last” —

then there would be a reasonable case for filling American schools with

law enforcement agents and increasing the use of juvenile detention.

And the right is already making that case: In recent days, conservative media outlets have suggested that the Parkland shooting could have been prevented if only Broward County hadn’t implemented the PROMISE program

(Preventing Recidivism through Opportunities, Mentoring, Interventions,

Supports & Education) in 2013 — a policy that aimed to reduce

juvenile arrests by promoting non-carceral approaches to correcting

student misbehavior.

All

of which is to say: The Parkland teenagers, and the movement they have

launched, has made a vital contribution to American politics. They’ve

stiffened the spines of Democratic gun safety advocates; unnerved

Republican NRA stooges; improved the prospects of meaningful gun reform

at the federal level in the medium-term; and provided a model of civic

engagement to a rising generation whose political participation our

country desperately needs.

But

to ensure that those contributions aren’t shadowed by the unintended

consequences of overheated rhetoric, the March for Our Lives and its

supporters must take pains to ensure that their advocacy always affirms

this basic truth: Schools don’t kill people, guns kill people.

No comments:

Post a Comment