Eli E. Hertz

“When it is asked what is meant by the development of the Jewish

National Home in Palestine, it may be answered that it is not the

imposition of a Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants of Palestine as a

whole, but the further development of the existing Jewish community,

with the assistance of Jews in other parts of the world, in order that

it may become a centre in which the Jewish people as a whole may take,

on grounds of religion and race, an interest and a pride. But in order

that this community should have the best prospect of free development

and provide a full opportunity for the Jewish people to display its

capacities, it is essential that it should know that it is in Palestine

as of right and not on sufferance.”

Winston Churchill

British Secretary of State for the Colonies

June 1922

Ever ask yourself why during the 30 year period - between 1917 to

1947 - thousands of Jews throughout the world woke up one morning and

decided to leave their homes and go to Palestine? The majority did this

because they heard that a future national home for the Jewish people was

being established in Palestine, on the basis of the League of Nations

obligation under the “Mandate for Palestine” document. The “Mandate for

Palestine,” an historical League of Nations document, laid down the

Jewish legal right to settle anywhere in western Palestine, between the

Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, an entitlement unaltered in

international law. The “Mandate for Palestine” was not a naive vision

briefly embraced by the international community. Fifty-one member

countries – the entire League of Nations – unanimously declared on July

24, 1922:

“Whereas recognition has been given to the historical

connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for

reconstituting their national home in that country.”

It is important to point out that political rights to

self-determination as a polity for Arabs were guaranteed by the same

League of Nations in four other mandates – in Lebanon and Syria (The

French Mandate), Iraq, and later Trans-Jordan [The British Mandate].

Any attempt to negate the Jewish people’s right to

Palestine - Eretz-Israel, and to deny them access and control in the

area designated for the Jewish people by the League of Nations is a

serious infringement of international law.

The “Road Map” vision, as

well as continuous pressure from the “Quartet” (U.S., the European

Union, the UN and Russia) to surrender parts of Eretz-Israel are

contrary to international law that firmly call to “encourage … close

settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands

not required for public purposes.” It also requires the Mandatory for

“seeing that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in

any way placed under the control of the government of any foreign

power.”

In their attempt to establish peace between the

Jewish state and its Arab neighbors, the nations of the world should

remember who the lawful sovereign is with its rights anchored in

international law, valid to this day: The Jewish Nation. And in support

of the Jewish people, I sat down and wrote this pamphlet.

Eli E. Hertz

I. The Founding of Modern Zionism

Benjamin Ze’ev (Theodor) Herzl

(May 2, 1860 – July 3, 1904)

After witnessing the spread of antisemitism around the world, Herzl

felt compelled to create a political movement with the goal of

establishing a Jewish National Home in Palestine. To this end, he

assembled the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897.

Herzl’s insights and vision can be learned from his writings:

“Oppression and persecution

cannot exterminate us. No nation on earth has survived such struggles

and sufferings as we have gone through.

“Palestine is our ever-memorable

historic home. The very name of Palestine would attract our people with

a force of marvelous potency.

“The idea which I have developed in this pamphlet is a very old one: it is the restoration of the Jewish State.

“The world resounds with

outcries against the Jews, and these outcries have awakened the

slumbering idea. ... We are a people - one people.”

1

The British Foreign Office, November 2nd, 1917

Dear Lord Rothschild, I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on

behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of

sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to,

and approved by, the Cabinet.

“His Majesty’s Government

view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for

the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the

achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing

shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of

existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and

political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.

2

Signed,

Arthur James Balfour

[Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs]

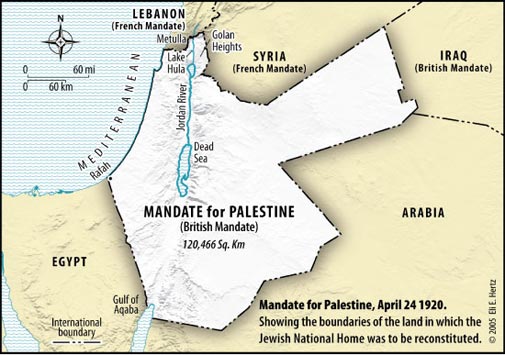

The “Mandate for Palestine,” an historical

League of Nations document, laid down the Jewish legal right to settle

anywhere in western Palestine, a 10,000-square-miles

3 area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

The legally binding document was conferred on

April 24, 1920 at the San Remo Conference, and its terms outlined in the

Treaty of Sèvres on August 10, 1920. The Mandate’s terms were finalized

and unanimously approved on July 24, 1922, by the Council of the League

of Nations, which was comprised at that time of 51 countries,

4 and became operational on September 29, 1923.

5

The “Mandate for Palestine” was not a naive

vision briefly embraced by the international community in blissful

unawareness of Arab opposition to the very notion of Jewish historical

rights in Palestine. The Mandate weathered the test of time: On April

18, 1946, when the League of Nations was dissolved and its assets and

duties transferred to the United Nations, the international community,

in essence, reaffirmed the validity of this international accord and

reconfirmed that the terms for a Jewish National Home were the will of

the international community, a “sacred trust” – despite the fact that by

then it was patently clear that the Arabs opposed a Jewish National

Home, no matter what the form.

Many seem to confuse the

“Mandate for Palestine” [The Trust], with the British Mandate [The

Trustee]. The “Mandate for Palestine” is a League of Nations document

that laid down the Jewish legal rights in Palestine. The British

Mandate, on the other hand, was entrusted by the League of Nations with

the responsibility to administrate the area delineated by the “Mandate

for Palestine.”

Great Britain [i.e., the Mandatory or

Trustee] did turn over its responsibility to the United Nations as of

May 14, 1948. However, the legal force of the League of Nations’

“Mandate for Palestine” [i.e., The Trust] was not terminated with the

end of the British Mandate. Rather, the Trust was transferred over to

the United Nations.

Fifty-one member countries – the entire League of Nations – unanimously declared on July 24, 1922:

“Whereas recognition has been

given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine

and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that

country.”

6

Unlike nation-states in Europe, modern

Lebanese, Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi nationalities did not evolve.

They were arbitrarily created by colonial powers.

In 1919, in the wake of World War I, England

and France as Mandatory (e.g., official administrators and mentors)

carved up the former Ottoman Empire, which had collapsed a year earlier,

into geographic spheres of influence. This divided the Mideast into new

political entities with new names and frontiers.

7

Territory was divided along map meridians

without regard for traditional frontiers (i.e., geographic logic and

sustainability) or the ethnic composition of indigenous populations.

8

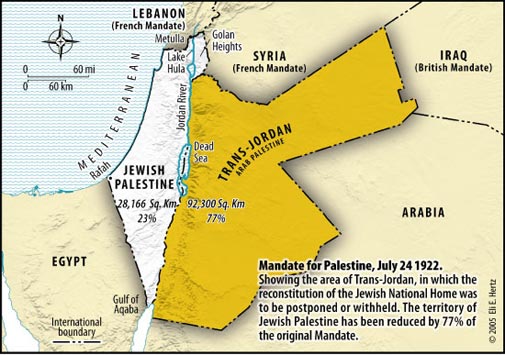

The prevailing rationale behind these

artificially created states was how they served the imperial and

commercial needs of their colonial masters. Iraq and Jordan, for

instance, were created as emirates to reward the noble Hashemite family

from Saudi Arabia for its loyalty to the British against the Ottoman

Turks during World War I, under the leadership of Lawrence of Arabia.

Iraq was given to Faisal bin Hussein, son of the sheriff of Mecca, in

1918. To reward his younger brother Abdullah with an emirate, Britain

cut away 77 percent of its mandate over Palestine earmarked for the Jews

and gave it to Abdullah in 1922, creating the new country of

Trans-Jordan or Jordan, as it was later named.

The Arabs’ hatred of the Jewish State has

never been strong enough to prevent the bloody rivalries that repeatedly

rock the Middle East. These conflicts were evident in the civil wars in

Yemen and Lebanon, as well as in the war between Iraq and Iran, in the

gassing of countless Kurds in Iraq, and in the killing of Iraqis by

Iraqis.

The manner in which European colonial powers

carved out political entities with little regard to their ethnic

composition not only led to this inter-ethnic violence, but it also

encouraged dictatorial rule as the only force capable of holding such

entities together.

9

The exception was Palestine, or Eretz-Israel – the territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, where:

“The Mandatory shall be

responsible for placing the country [ Palestine] under such political,

administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment

of the Jewish National Home, as laid down in the preamble, and the

development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding

the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine,

irrespective of race and religion.”

10

Delineating the final geographical area of

Palestine designated for the Jewish National Home on September 16, 1922,

as described by the Mandatory:

11

PALESTINE

INTRODUCTORY.

POSITION, ETC.

Palestine lies on the

western edge of the continent of Asia between Latitude 30º N. and 33º

N., Longitude 34º 30’ E. and 35º 30’ E.

On the North it is bounded

by the French Mandated Territories of Syria and Lebanon, on the East by

Syria and Trans-Jordan, on the South-west by the Egyptian province of

Sinai, on the South-east by the Gulf of Aqaba and on the West by the

Mediterranean. The frontier with Syria was laid down by the Anglo-French

Convention of the 23rd December, 1920, and its delimitation was

ratified in 1923. Briefly stated, the boundaries are as follows: -

North. – From Ras en

Naqura on the Mediterranean eastwards to a point west of Qadas, thence

in a northerly direction to Metulla, thence east to a point west of

Banias.

East. – From Banias

in a southerly direction east of Lake Hula to Jisr Banat Ya’pub, thence

along a line east of the Jordan and the Lake of Tiberias and on to El

Hamme station on the Samakh-Deraa railway line, thence along the centre

of the river Yarmuq to its confluence with the Jordan, thence along the

centres of the Jordan, the Dead Sea and the Wadi Araba to a point on the

Gulf of Aqaba two miles west of the town of Aqaba, thence along the

shore of the Gulf of Aqaba to Ras Jaba.

South. – From Ras

Jaba in a generally north-westerly direction to the junction of the

Neki-Aqaba and Gaza-Aqaba Roads, thence to a point west-north-west of

Ain Maghara and thence to a point on the Mediterranean coast north-west

of Rafa.

West. – The Mediterranean Sea.

Arabs, the UN and its organs, and lately the

International Court of Justice (ICJ) as well, have repeatedly claimed

that the Palestinians are a native people – so much so that almost

everyone takes it for granted. The problem is that a stateless

Palestinian people is a fabrication. The word Palestine is not even

Arabic.

12

In a report by His Majesty’s Government in the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Council of

the League of Nations on the administration of Palestine and

Trans-Jordan for the year 1938, the British made it clear: Palestine is

not a State, it is the name of a geographical area.

13

Palestine is a name coined by the Romans

around 135 CE from the name of a seagoing Aegean people who settled on

the coast of Canaan in antiquity – the Philistines. The name was chosen

to replace Judea, as a sign that Jewish sovereignty had been eradicated

following the Jewish Revolts against Rome.

In the course of time, the Latin name Philistia was further bastardized into Palistina or Palestine.

14

During the next 2,000 years Palestine was never an independent state

belonging to any people, nor did a Palestinian people distinct from

other Arabs appear during 1,300 years of Muslim hegemony in Palestine

under Arab and Ottoman rule. During that rule, local Arabs were actually

considered part of, and subject to, the authority of Greater Syria (

Suriyya al-Kubra).

15

Historically, before the Arabs fabricated the

concept of Palestinian peoplehood as an exclusively Arab phenomenon, no

such group existed. This is substantiated in countless official British

Mandate-vintage documents that speak of the Jews and the Arabs of

Palestine – not Jews and Palestinians.

16

In fact, before local Jews began calling

themselves Israelis in 1948 (when the name “Israel” was chosen for the

newly-established Jewish State), the term “Palestine” applied almost

exclusively to Jews and the institutions founded by new Jewish

immigrants in the first half of the 20th century, before the state’s

independence.

Some examples include:

The Jerusalem Post, founded in 1932, was called

The Palestine Post until 1948.

Bank Leumi L’Israel, incorporated in 1902, was called the “Anglo-Palestine Company” until 1948.

The Jewish Agency – an arm of the Zionist

movement engaged in Jewish settlement since 1929 – was initially called

the Jewish Agency for Palestine.

Today’s Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, founded

in 1936 by German Jewish refugees who fled Nazi Germany, was originally

called the “Palestine Symphony Orchestra,” composed of some 70

Palestinian Jews.

17

The United Jewish Appeal (UJA) was established

in 1939 as a merger of the United Palestine Appeal and the fund-raising

arm of the Joint Distribution Committee.

Encouraged by their success at historical

revisionism and brainwashing the world with the “Big Lie” of a

Palestinian people, Palestinian Arabs have more recently begun to claim

they are the descendants of the Philistines and even the Stone Age

Canaanites.

18

Based on that myth, they can claim to have been “victimized” twice by

the Jews: in the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites and again by the

Israelis in modern times – a total fabrication.

19

Archeologists explain that the Philistines were a Mediterranean people

who settled along the coast of Canaan in 1100 BCE. They have no

connection to the Arab nation, a desert people who emerged from the

Arabian Peninsula.

As if that myth were not enough, former PLO

Chairman Yasir Arafat also claimed, “Palestinian Arabs are descendants

of the Jebusites,” who were displaced when King David conquered

Jerusalem.

Arafat also argued that “Abraham was an

Iraqi.” One Christmas Eve, Arafat declared that “Jesus was a

Palestinian,” a preposterous claim that echoes the words of Hanan

Ashrawi, a Christian Arab who, in an interview during the 1991 Madrid

Conference, said: “Jesus Christ was born in my country, in my land,” and

claimed that she was “the descendant of the first Christians,”

disciples who spread the gospel around Bethlehem some 600 years before

the Arab conquest. If her claims were true, it would be tantamount to

confessing that she is a Jew!

Contradictions abound; Palestinian leaders

claim to be descended from the Canaanites, the Philistines, the

Jebusites and the first Christians. They also “hijacked” Jesus and

ignored his Jewishness, at the same time claiming the Jews never were a

people and never built the Holy Temples in Jerusalem.

The artificiality of a Palestinian identity is

reflected in the attitudes and actions of neighboring Arab nations who

never established a Palestinian state themselves.

The rhetoric by Arab leaders on behalf of the

Palestinians rings hollow. Arabs in neighboring states, who control 99.9

percent of the Middle East land, have never recognized a Palestinian

entity. They have always considered Palestine and its inhabitants part

of the great “Arab nation,” historically and politically as an integral

part of Greater Syria – Suriyya al-Kubra – a designation that extended

to both sides of the Jordan River.

20

In the 1950s, Jordan simply annexed the West Bank since the population

there was viewed as the brethren of the Jordanians. Jordan’s official

narrative of “Jordanian state-building” attests to this fact:

“Jordanian identity underlies the signific ant

and fundamental common denominator that makes it inclusive of

Palestinian identity, particularly in view of the shared historic social

and political development of the people on both sides of the Jordan.

... The Jordan government, in view of the historical and political

relationship with the West Bank ... granted all Palestinian refugees on

its territory full citizenship rights while protecting and upholding

their political rights as Palestinians (Right of Return or

compensation).”

21

The Arabs never established a Palestinian

state when the UN in 1947 recommended to partition Palestine, and to

establish “an Arab and a Jewish state” (not a Palestinian state, it

should be noted). Nor did the Arabs recognize or establish a Palestinian

state during the two decades prior to the Six-Day War when the West

Bank was under Jordanian control and the Gaza Strip was under Egyptian

control; nor did the Palestinian Arabs clamor for autonomy or

independence during those years under Jordanian and Egyptian rule.

Only twice in Jerusalem’s history has the city

served as a national capital. First as the capital of the two Jewish

Commonwealths during the First and Second Temple periods, as described

in the Bible, reinforced by archaeological evidence and numerous ancient

documents. And again in modern times as the capital of the State of

Israel. It has never served as an Arab capital for the simple reason

that there has never been a Palestinian Arab state.

Well before the 1967 decision to create a new

Arab people called “Palestinians,” when the word “Palestinian” was

associated with Jewish endeavors, Auni Bey Abdul-Hadi, a local Arab

leader, testified in 1937 before the Peel Commission, a British

investigative body:

“There is no such country [as

Palestine]! Palestine is a term the Zionists invented! There is no

Palestine in the Bible. Our country was for centuries, part of Syria.”

22

In a 1946 appearance before the Anglo-American

Committee of Inquiry, also acting as an investigative body, the

Arab-American historian Philip Hitti stated:

“There is no such thing as

Palestine in [Arab] history, absolutely not.” According to investigative

journalist Joan Peters, who spent seven years researching the origins

of the Arab-Jewish conflict over Palestine (From Time Immemorial, 2001),

the one identity that was never considered by local inhabitants prior

to the 1967 war was “Arab Palestinian.”

23

The “Mandate for Palestine” document did not

set final borders. It left this for the Mandatory to stipulate in a

binding appendix to the final document in the form of a memorandum.

However, Article 6 of the “Mandate” clearly states:

“The Administration of

Palestine, while ensuring that the rights and position of other sections

of the population are not prejudiced, shall facilitate Jewish

immigration under suitable conditions and shall encourage, in

co-operation with the Jewish agency referred to in Article 4, close

settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands

not required for public purposes.”

Article 25 of the “Mandate for Palestine”

entitled the Mandatory to change the terms of the Mandate in the

territory east of the Jordan River:

“In the territories lying

between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately

determined, the Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the

Council of the League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of

such provision of this Mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the

existing local conditions ...”

Great Britain activated this option in the

above-mentioned memorandum of September 16, 1922, which the Mandatory

sent to the League of Nations and which the League subsequently approved

– making it a legally binding integral part of the “Mandate.”

Thus the “Mandate for Palestine” brought to

fruition a fourth Arab state east of the Jordan River, realized in 1946

when the Hashemite Kingdom of Trans-Jordan was granted independence from

Great Britain.

All the clauses concerning a Jewish National

Home would not apply to this territory [Trans-Jordan] of the original

Mandate, as is clearly stated:

“The following provisions of the

Mandate for Palestine are not applicable to the territory known as

Trans-Jordan, which comprises all territory lying to the east of a line

drawn from ... up the centre of the Wady Araba, Dead Sea and River

Jordan. ... His Majesty’s Government accept[s] full responsibility as

Mandatory for Trans-Jordan.”

The creation of an Arab state in eastern

Palestine (today Jordan) on 77 percent of the landmass of the original

Mandate intended for a Jewish National Home in no way changed the status

of Jews west of the Jordan River, nor did it inhibit their right to

settle anywhere in western Palestine, the area between the Jordan River

and the Mediterranean Sea.

These documents are the last legally binding

documents regarding the status of what is commonly called “the West Bank

and Gaza.”

The September 16, 1922 memorandum is also the

last modification of the official terms of the Mandate on record by the

League of Nations or by its legal successor – the United Nations – in

accordance with Article 27 of the Mandate that states unequivocally:

“The consent of the Council of the League of Nations is required for any modification of the terms of this mandate.”

24

United Nations Charter recognizes the UN’s obligation to uphold the commitments of its predecessor – the League of Nations.

25

The “Mandate for Palestine” clearly

differentiates between political rights – referring to Jewish

self-determination as an emerging polity – and civil and religious

rights, referring to guarantees of equal personal freedoms to non-Jewish

residents as individuals and within select communities. Not once are

Arabs as a people mentioned in the “Mandate for Palestine.” At no point

in the entire document is there any granting of political rights to

non-Jewish entities (i.e., Arabs). Article 2 of the “Mandate for

Palestine” explicitly states that the Mandatory should:

“... be responsible for placing

the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions

as will secure the establishment of the Jewish National Home, as laid

down in the preamble, and the development of self-governing

institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights

of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.”

Political rights to self-determination as a

polity for Arabs were guaranteed by the League of Nations in four other

mandates – in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and later Trans-Jordan [today

Jordan].

International law expert Professor Eugene V.

Rostow, examining the claim for Arab Palestinian self-determination on

the basis of law, concluded:

“… the mandate implicitly

denies Arab claims to national political rights in the area

in favor of the Jews;

the mandated territory was in effect reserved to the Jewish people for

their self-determination and political development, in acknowledgment of

the historic connection of the Jewish people to the land. Lord Curzon,

who was then the British Foreign Minister, made this reading of the

mandate explicit. There remains simply the theory that the Arab

inhabitants of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip have an inherent

‘natural law’ claim to the area. Neither customary international law nor

the United Nations Charter acknowledges that every group of people

claiming to be a nation has the right to a state of its own.”

26 [italics by author]

It is remarkable to note the April 22, 1925

Report of the first High Commissioner on the Administration of

Palestine, Sir Herbert Louis Samuel, to the Right Honourable L. S.

Amery, M.P., Secretary of State for the Colonies’ Government Offices,

describing Jewish Peoplehood:

“During the last two or three

generations the Jews have recreated in Palestine a community, now

numbering 80,000, of whom about one-fourth are farmers or workers upon

the land. This community has its own political organs, an elected

assembly for the direction of its domestic concerns, elected councils in

the towns, and an organisation for the control of its schools. It has

its elected Chief Rabbinate and Rabbinical Council for the direction of

its religious affairs. Its business is conducted in Hebrew as a

vernacular language, and a Hebrew press serves its needs. It has its

distinctive intellectual life and displays considerable economic

activity. This community, then, with its town and country population,

its political, religious and social organisations, its own language, its

own customs, its own life, has in fact national characteristics.” [italics by author]

Two distinct issues exist: the issue of Jerusalem and the issue of the Holy Places.

Cambridge Professor Sir Elihu Lauterpacht,

Judge ad hoc of the International Court of Justice and a renowned editor

of one of the ‘bibles’ of international law, International Law Reports

has said:

“Not only are the two problems

separate; they are also quite distinct in nature from one another. So

far as the Holy Places are concerned, the question is for the most part

one of assuring respect for the existing interests of the three

religions and of providing the necessary guarantees of freedom of

access, worship, and religious administration [E.H., as mandated in

Article 13 and 14 of the “Mandate for Palestine”] … As far as the City

of Jerusalem itself is concerned, the question is one of establishing an

effective administration of the City which can protect the rights of

the various elements of its permanent population - Christian, Arab and

Jewish - and ensure the governmental stability and physical security

which are essential requirements for the city of the Holy Places.”

27

The notion of internationalizing Jerusalem was never part of the “Mandate”:

“Nothing was said in the Mandate

about the internationalization of Jerusalem. Indeed Jerusalem as such

is not mentioned – though the Holy Places are. And this in itself is a

fact of relevance now. For it shows that in 1922 there was no

inclination to identify the question of the Holy Places with that of the

internationalization of Jerusalem.”

28

Jerusalem the spiritual, political, and

historical capital of the Jewish people has served, and still serves, as

the political capital of only one nation – the one belonging to the

Jewish people.

Jerusalem, a city in Palestine, was and is an undisputed part of the Jewish National Home.

In the first Report of the High Commissioner

on the Administration of Palestine (1920-1925) presented to the British

Secretary of State for the Colonies, published in April 1925, the most

senior official of the Mandate, the High Commissioner for Palestine,

underscored how international guarantees for the existence of a Jewish

National Home in Palestine were achieved:

“The [Balfour] Declaration was

endorsed at the time by several of the Allied Governments; it was

reaffirmed by the Conference of the Principal Allied Powers at San Remo

in 1920; it was subsequently endorsed by unanimous resolutions of both

Houses of the Congress of the United States; it was embodied in the

Mandate for Palestine approved by the League of Nations in 1922; it was

declared, in a formal statement of policy issued by the Colonial

Secretary in the same year, ‘not to be susceptible of change.’ ”

29

Far from the whim of this or that politician

or party, eleven successive British governments, Labor and Conservative,

from David Lloyd George (1916-1922) through Clement Attlee (1945-1952)

viewed themselves as duty-bound to fulfill the “Mandate for Palestine”

placed in the hands of Great Britain by the League of Nations.

United States President Woodrow Wilson (the

twenty-eighth President, 1913-1921) was the founder of the League of

Nations for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919.

Wilson 's efforts to join the Unites States

as a member of the League of Nations were unsuccessful due to

oppositions in the U.S. Senate. Despite not being a member of the

League, the U.S. Government claimed on November 20, 1920 that the

participation of the United States in WWI entitled it to be consulted as

to the terms of the Mandate. The British Government agreed, and the

outcome was an agreement calling to safeguard the American interests in

Palestine. It concluded with a convention between the United Kingdom and

the United States of America, signed on December 3, 1924. It is

imperative to note that the convention incorporated the complete text of

the “Mandate for Palestine,” including the preamble!

30

President Wilson was the first American

president to support modern Zionism and Britain’s efforts for the

creation of a National Home for Jews in Palestine (the text of the

Balfour Declaration had been submitted to President Wilson and had been

approved by him before its publication).

President Wilson expressed his deep belief in the eventuality of the creation of a Jewish State:

“I am persuaded,” said President

Wilson on March 3rd, 1919, “that the Allied nations, with the fullest

concurrence of our own Government and people, are agreed that in

Palestine shall be laid the foundation of a Jewish Commonwealth.”

31

On June 30, 1922, a joint resolution of both

Houses of Congress of the United States unanimously endorsed the

“Mandate for Palestine,” confirming the irrevocable right of Jews to

settle in the area of Palestine – anywhere between the Jordan River and

the Mediterranean Sea:

“Favoring the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.

“Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled.

That the United States of America favors the establishment in Palestine

of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood

that nothing shall be done which should prejudice the civil and

religious rights of Christian and all other non-Jewish communities in

Palestine, and that the holy places and religious buildings and sites in

Palestine shall be adequately protected.”

32 [italics in the original]

On September 21, 1922, President Warren G.

Harding (the twenty-ninth President, 1921-1923) signed the joint

resolution of approval to establish a Jewish National Home in Palestine.

The Mandate survived the demise of the League

of Nations. Article 80 of the UN Charter implicitly recognizes the

“Mandate for Palestine” of the League of Nations.

This Mandate granted Jews the irrevocable

right to settle anywhere in Palestine, the area between the Jordan River

and the Mediterranean Sea, a right unaltered in international law and

valid to this day. Jewish settlements in Judea and Samaria (i.e. the

West Bank), Gaza and the whole of Jerusalem are legal.

The International Court of Justice reaffirmed the meaning and validity of Article 80 in three separate cases:

- ICJ Advisory Opinion of July 11, 1950: in the “question concerning the International States of South West Africa.”33

- ICJ Advisory Opinion of June 21, 1971: “When the League of Nations was dissolved, the raison d’etre

[French: “reason for being”] and original object of these obligations

remained. Since their fulfillment did not depend on the existence of the

League, they could not be brought to an end merely because the

supervisory organ had ceased to exist. ... The International Court of

Justice has consistently recognized that the Mandate survived the demise

of the League [of Nations].”

- ICJ Advisory Opinion of July 9, 2004:

regarding the “legal consequences of the construction of a wall in the

occupied Palestinian territory.”35

In other words, neither the ICJ nor the UN

General Assembly can arbitrarily change the status of Jewish settlement

as set forth in the “Mandate for Palestine,” an international accord

that has never been amended.

All of western Palestine, from the Jordan

River to the Mediterranean Sea, including the West Bank and Gaza,

remains open to Jewish settlement under international law.

Professor Eugene Rostow concurred with the ICJ’s opinion as to the “sacredness” of trusts such as the “Mandate for Palestine”:

“‘A trust’ – as in Article 80 of

the UN Charter – does not end because the trustee dies ... the Jewish

right of settlement in the whole of western Palestine – the area west of

the Jordan – survived the British withdrawal in 1948. ... They are

parts of the mandate territory, now legally occupied by Israel with the

consent of the Security Council.”

36

The British Mandate left intact the Jewish right to settle in Judea, Samaria and the Gaza Strip. Explains Professor Rostow:

“This right is protected by

Article 80 of the United Nations Charter, which provides that unless a

trusteeship agreement is agreed upon (which was not done for the

Palestine Mandate), nothing in the chapter shall be construed in and of

itself to alter in any manner the rights whatsoever of any states or any

peoples or the terms of existing international instruments to which

members of the United Nations may respectively be parties.

“The Mandates of the League of

Nations have a special status in international law. They are considered

to be trusts, indeed ‘sacred trusts.’

“Under international law,

neither Jordan nor the Palestinian Arab ‘people’ of the West Bank and

the Gaza Strip have a substantial claim to the sovereign possession of

the occupied territories.”

It is interesting to learn how Article 80 made its way into the UN Charter. Professor Rostow recalls:

“I am indebted to my learned

friend Dr. Paul Riebenfeld, who has for many years been my mentor on the

history of Zionism, for reminding me of some of the circumstances which

led to the adoption of Article 80 of the Charter. Strong Jewish

delegations representing differing political tendencies within Jewry

attended the San Francisco Conference in 1945. Rabbi Stephen S. Wise,

Peter Bergson, Eliahu Elath, Professors Ben-Zion Netanayu and A. S.

Yehuda, and Harry Selden were among the Jewish representatives. Their

mission was to protect the Jewish right of settlement in Palestine under

the mandate against erosion in a world of ambitious states. Article 80

was the result of their efforts.”

37

There is much to be gained by attributing

Class “A” status to the “Mandate for Palestine.” If the inhabitants of

Palestine were ready for independence under a Class “A” mandate, then

the Palestinian Arabs that made up the majority of the inhabitants of

Palestine in 1922

38

(589,177 Arabs vs. 83,790 Jews) could then logically claim that they

were the intended beneficiaries of the “Mandate for Palestine” –

provided one never reads the actual wording of the document:

1. The “Mandate for Palestine” never mentions Class “A” status at any time for Palestinian Arabs.

2. Article 2 of the document clearly speaks of the Mandatory as being:

“... responsible for placing the

country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as

will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home.”

The “Mandate” calls for steps to encourage

Jewish immigration and settlement throughout Palestine except east of

the Jordan River. Historically, therefore, Palestine was an anomaly

within the Mandate system, in a class of its own – initially referred to

by the British as a “special regime.”

39

Many assume that the “Mandate for Palestine”

is a Class “A” mandate, a common but inaccurate assertion that can be

found in many dictionaries and encyclopedias, and is frequently used by

the pro-Palestinian media and lately by the ICJ. In the Court Advisory

Opinion of July 9, 2004, in the matter of the construction of a wall in

the “ Occupied Palestinian Territory,” the Bench erroneously stated:

“ Palestine was part of the

Ottoman Empire. At the end of the First World War, a class [type] ‘A’

Mandate for Palestine was entrusted to Great Britain by the League of

Nations, pursuant to paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant. ...”

40

Indeed, Class “A” status was granted to a

number of Arab peoples who were ready for independence in the former

Ottoman Empire, and only to Arab entities.

41 Palestinian Arabs were not one of these Arab peoples. The Palestine Royal Report clarifies this point:

“(2) The Mandate [for Palestine]

is of a different type from the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon and

the draft Mandate for Iraq. These latter, which were called for

convenience “A” Mandates, accorded with the fourth paragraph of Article

22. Thus the Syrian Mandate provided that the government should be based

on an organic law which should take into account the rights, interests

and wishes of all the inhabitants, and that measures should be enacted

‘to facilitate the progressive development of Syria and the Lebanon as

independent States.’ The corresponding sentences of the draft Mandate

for Iraq were the same. In compliance with them National Legislatures

were established in due course on an elective basis.

Article 1 of the Palestine

Mandate, on the other hand, vests ‘full powers of legislation and of

administration,’ within the limits of the Mandate, in the Mandatory.”

42

The Palestine Royal Report highlights additional differences between the Mandates:

“Unquestionably, however, the

primary purpose of the Mandate, as expressed in its preamble and its

articles, is to promote the establishment of the Jewish National Home.

“... Articles 4, 6 and 11

provide for the recognition of a Jewish Agency ‘as a public body for the

purpose of advising and co-operating with the Administration’ on

matters affecting Jewish interests. No such body is envisaged for

dealing with Arab interests.

43

“... But Palestine was different

from the other ex-Turkish provinces. It was, indeed, unique both as the

Holy Land of three world-religions and as the old historic national

home of the Jews. The Arabs had lived in it for centuries, but they had

long ceased to rule it, and in view of its peculiar character they could

not now claim to possess it in the same way as they could claim

possession of Syria or Iraq.”

44

The Palestinian [British] Royal Commission

Report of July 1937 addressed Arab claims that the creation of the

Jewish National Home as directed by the “Mandate for Palestine” violated

Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations,

45 arguing that they are the communities mentioned in paragraph 4:

“ As to the claim, argued before

us by Arab witnesses, that the Palestine Mandate violates Article 22 of

the Covenant because it is not in accordance with paragraph 4 thereof,

we would point out (a) that the provisional recognition of ‘certain

communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire’ as independent

nations is permissive; the words are ‘can be provisionally recognised,’

not ‘will’ or ‘shall’: (b) that the penultimate paragraph of Article 22

prescribes that the degree of authority to be exercised by the Mandatory

shall be defined, at need, by the Council of the League: (c) that the

acceptance by the Allied Powers and the United States of the policy of

the Balfour Declaration made it clear from the beginning that Palestine

would have to be treated differently from Syria and Iraq, and that this

difference of treatment was confirmed by the Supreme Council in the

Treaty of Sèvres and by the Council of the League in sanctioning the

Mandate.

“This particular question is of

less practical importance than it might seem to be. For Article 2 of the

Mandate requires ‘the development of self-governing institutions’; and,

read in the light of the general intention of the Mandate System (of

which something will be said presently), this requirement implies, in

our judgment, the ultimate establishment of independence.

“(3) The field [Territory] in

which the Jewish National Home was to be established was understood, at

the time of the Balfour Declaration, to be the whole of historic

Palestine, and the Zionists were seriously disappointed when

Trans-Jordan was cut away from that field [Territory] under Article 25.”

[E.H., That excluded 77 percent of historic Palestine – the territory

east of the Jordan River, what became later Trans-Jordan]

45

The Treaty of Sèvres, in Section VII, Articles

94 and 95, makes it clear in each case who are the inhabitants referred

to in Paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of

Nations.

Article 94 distinctly indicates that Paragraph

4 of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations applies to the

Arab inhabitants living within the areas covered by the Mandates for

Syria and Mesopotamia. The Article reads:

“The High Contracting Parties agree that Syria and Mesopotamia shall, in accordance with the fourth paragraph of Article 22.

“Part I (Covenant of the League

of Nations), be provisionally recognised as independent States subject

to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory

until such time as they are able to stand alone...”

Article 95 of the Treaty of Sèvres, however,

makes it clear that paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant of the

League of Nations was not to be applied to the Arab inhabitants living

within the area to be delineated by the “Mandate for Palestine,” but

only to the Jews. The Article reads:

“The High Contracting Parties

agree to entrust, by application of the provisions of Article 22, the

administration of Palestine, within such boundaries as may be determined

by the Principal Allied Powers, to a Mandatory to be selected by the

said Powers. The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect

the declaration originally made on November 2, 1917, by the British

Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the

establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it

being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice

the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in

Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any

other country…”

47

The second and third paragraphs of the preamble of the “Mandate for Palestine” therefore follow and read:

“Whereas the Principal Allied

Powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for

putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2, 1917,

by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said

Powers, in favor of the establishment in Palestine of a national home

for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should

be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing

non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status

enjoyed by the Jews in any other country; and

“Whereas recognition has thereby

been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with

Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in

that

country. ”

48 [italics by author]

Articles 94 and 95 of the Treaty of Sèvres and the “Mandate for Palestine” make it clear:

The “inhabitants” of the

territory for whom the “Mandate for Palestine” was created, who

according to the Mandate were “not yet able” to govern themselves and

for whom self-determination was a “sacred trust,” were not Palestinians,

or even Arabs. The “Mandate for Palestine” was created by the

predecessor of the United Nations, the League of Nations , for the

Jewish People.

Addressing the Arab claim that Palestine was

part of the territories promised to the Arabs in 1915 by Sir Henry

McMahon, the British Government stated:

“We think it sufficient for the

purposes of this Report to state that the British Government have never

accepted the Arab case. When it was first formally presented by the Arab

Delegation in London in 1922, the Secretary of State for the Colonies

(Mr. Churchill) replied as follows: – ‘That letter [Sir H. McMahon’s

letter of the 24th October, 1915] is quoted as conveying the promise to

the Sherif of Mecca to recognize and support the independence of the

Arabs within the territories proposed by him. But this promise was given

subject to a reservation made in the same letter, which excluded from

its scope, among other territories, the portions of Syria lying to the

west of the district of Damascus. This reservation has always been

regarded by His Majesty’s Government as covering the vilayet of Beirut

and the independent Sanjak of Jerusalem. The whole of Palestine west of

the Jordan was thus excluded from Sir H. McMahon’s pledge.’

“It was in the highest degree

unfortunate that, in the exigencies of war, the British Government was

unable to make their intention clear to the Sherif. Palestine, it will

have been noticed, was not expressly mentioned in Sir Henry McMahon’s

letter of the 24th October, 1915. Nor was any later reference made to

it. In the further correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and the

Sherif the only areas relevant to the present discussion which were

mentioned were the Vilayets of Aleppo and Beirut. The Sherif asserted

that these Vilayets were purely Arab; and, when Sir Henry McMahon

pointed out that French interests were involved, he replied that, while

he did not recede from his full claims in the north, he did not wish to

injure the alliance between Britain and France and would not ask ‘for

what we now leave to France in Beirut and its coasts’ till after the

War.”

49

McMahon wrote a letter to The Times [of

London] on July 23, 1937, confirming that Palestine was excluded from

the area in which Arab independence was promised and that this was well

understood by King Hussein.

50

Israel’s pre-1967 borders reflected the

deployment of Israeli and Arab forces on the ground after Israel’s War

of Independence in 1948. Professor Judge Stephen M. Schwebel, the former

President of the International Court of Justice clarified in his

writings “Justice in International Law” that the 1949 armistice

demarcation lines are not permanent borders:

“... The armistice agreements of

1949 expressly preserved the territorial claims of all parties and did

not purport to establish definitive boundaries between them.”

51

United Nations Security Resolution 54 (July 15, 1948) called upon the Arabs to accept a truce and stop their aggression:

“

Taking into consideration

that the Provisional Government of Israel has indicated its acceptance

in principle of a prolongation of the truce in Palestine; that the

States members of the Arab League have rejected successive appeals of

the United Nations Mediator, and of the Security Council in its

resolution 53 (1948) of 7 July 1948, for the prolongation of the truce

in Palestine; and that there has consequently developed a renewal of

hostilities in Palestine.”

52

The demarcation line that emerged in the

aftermath of the war was drawn up under the auspices of United Nations

mediator Dr. Ralph Johnson Bunche. That new boundary largely reflected

the ceasefire lines of 1949 and was labeled the “Green Line” merely

because a green pencil was used to draw the map of the armistice

borders.

The PLO Charter, also known as “the

Palestinian National Charter” or “the Palestinian Covenant,” was adopted

by the Palestine National Council (PNC) on July 1-17, 1968. It reads:

“Article 2: Palestine, with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit.

“Article 9: Armed struggle is the only

way to liberate Palestine. Thus it is the overall strategy, not merely a

tactical phase. The Palestinian Arab people assert their absolute

determination and firm resolution to continue their armed struggle and

to work for an armed popular revolution for the liberation of their

country and their return to it. They also assert their right to normal

life in Palestine and to exercise their right to self-determination and

sovereignty over it.

“Article 19: The partition of

Palestine in 1947 and the establishment of the state of Israel are

entirely illegal, regardless of the passage of time, because they were

contrary to the will of the Palestinian people and to their natural

right in their homeland, and inconsistent with the principles embodied

in the Charter of the United Nations, particularly the right to

self-determination.

“Article 20: The Balfour Declaration,

the Mandate for Palestine, and everything that has been based upon them,

are deemed null and void. Claims of historical or religious ties of

Jews with Palestine are incompatible with the facts of history and the

true conception of what constitutes statehood. Judaism, being a

religion, is not an independent nationality. Nor do Jews constitute a

single nation with an identity of its own; they are citizens of the

states to which they belong.” 53

The FATEH Constitution (referred to, at time, as Fatah) calls under Article 12 for the:

“Complete liberation of Palestine, and obliteration of Zionist economic, political, military and cultural existence.”

As for how it will achieve its goal to wipe Israel off the map, Fateh’s constitution, Article 19, minces no words:

“Armed struggle is a strategy

and not a tactic, and the Palestinian Arab People’s armed revolution is a

decisive factor in the liberation fight and in uprooting the Zionist

existence, and this struggle will not cease unless the Zionist state is

demolished and Palestine is completely liberated.”

54 (acronym for “Islamic Resistance Movement” and at time referred to as the Hamas Covenant) states in its second paragraph:

55

“ Israel will rise and will

remain erect until Islam eliminates it as it had eliminated its

predecessors. The Martyr, Imam Hassan al-Banna, May Allah Pity his

Soul.”

LEAGUE OF NATIONS MANDATE FOR PALESTINE (Eretz-Israel) 56

TOGETHER WITH A

NOTE BY THE SECRETARY-GENERAL

RELATING TO ITS APPLICATION

TO THE

TERRITORY KNOWN AS TRANS-JORDAN,

under the provisions of Article 25

Presented to Parliament by Command of His Majesty,

December, 1922.

LONDON:

PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE

The Council of the League of Nations:

Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have

agreed, for the purpose of giving effect to the provisions of Article 22

of the Covenant of the League of Nations, to entrust to a Mandatory

selected by the said Powers the administration of the territory of

Palestine, which formerly belonged to the Turkish Empire, within such

boundaries as may be fixed by them; and

Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have also

agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect

the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government

of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said Powers, in favor of

the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,

it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might

prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish

communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by

Jews in any other country; and

Whereas recognition has thereby been given to

the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the

grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country; and

Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have selected His Britannic Majesty as the Mandatory for Palestine; and

Whereas the mandate in respect of Palestine

has been formulated in the following terms and submitted to the Council

of the League for approval; and

Whereas His Britannic Majesty has accepted the

mandate in respect of Palestine and undertaken to exercise it on behalf

of the League of Nations in conformity with the following provisions;

and

Whereas by the afore-mentioned Article 22

(paragraph 8), it is provided that the degree of authority, control or

administration to be exercised by the Mandatory, not having been

previously agreed upon by the Members of the League, shall be explicitly

defined by the Council of the League of Nations;

Confirming the said Mandate, defines its terms as follows:

Article 1.

The Mandatory shall have full powers of

legislation and of administration, save as they may be limited by the

terms of this mandate.

Article 2.

The Mandatory shall be responsible for placing

the country under such political, administrative and economic

conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home,

as laid down in the preamble, and the development of self-governing

institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights

of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.

Article 3.

The Mandatory shall, so far as circumstances permit, encourage local autonomy.

Article 4.

An appropriate Jewish agency shall be

recognised as a public body for the purpose of advising and co-operating

with the Administration of Palestine in such economic, social and other

matters as may affect the establishment of the Jewish national home and

the interests of the Jewish population in Palestine, and, subject

always to the control of the Administration to assist and take part in

the development of the country.

The Zionist organization, so long as its

organization and constitution are in the opinion of the Mandatory

appropriate, shall be recognised as such agency. It shall take steps in

consultation with His Britannic Majesty’s Government to secure the

co-operation of all Jews who are willing to assist in the establishment

of the Jewish national home.

Article 5.

The Mandatory shall be responsible for seeing

that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way

placed under the control of the Government of any foreign Power.

Article 6.

The Administration of Palestine, while

ensuring that the rights and position of other sections of the

population are not prejudiced, shall facilitate Jewish immigration under

suitable conditions and shall encourage, in co-operation with the

Jewish agency referred to in Article 4, close settlement by Jews on the

land, including State lands and waste lands not required for public

purposes.

Article 7.

The Administration of Palestine shall be

responsible for enacting a nationality law. There shall be included in

this law provisions framed so as to facilitate the acquisition of

Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take up their permanent residence in

Palestine.

Article 8.

The privileges and immunities of foreigners,

including the benefits of consular jurisdiction and protection as

formerly enjoyed by Capitulation or usage in the Ottoman Empire, shall

not be applicable in Palestine.

Unless the Powers whose nationals enjoyed the

afore-mentioned privileges and immunities on August 1, 1914, shall have

previously renounced the right to their re-establishment, or shall have

agreed to their non-application for a specified period, these privileges

and immunities shall, at the expiration of the mandate, be immediately

reestablished in their entirety or with such modifications as may have

been agreed upon between the Powers concerned.

Article 9.

The Mandatory shall be responsible for seeing

that the judicial system established in Palestine shall assure to

foreigners, as well as to natives, a complete guarantee of their rights.

Respect for the personal status of the various

peoples and communities and for their religious interests shall be

fully guaranteed. In particular, the control and administration of Wakfs

shall be exercised in accordance with religious law and the

dispositions of the founders.

Article 10.

Pending the making of special extradition

agreements relating to Palestine, the extradition treaties in force

between the Mandatory and other foreign Powers shall apply to Palestine.

Article 11.

The Administration of Palestine shall take all

necessary measures to safeguard the interests of the community in

connection with the development of the country, and, subject to any

international obligations accepted by the Mandatory, shall have full

power to provide for public ownership or control of any of the natural

resources of the country or of the public works, services and utilities

established or to be established therein. It shall introduce a land

system appropriate to the needs of the country, having regard, among

other things, to the desirability of promoting the close settlement and

intensive cultivation of the land.

The Administration may arrange with the Jewish

agency mentioned in Article 4 to construct or operate, upon fair and

equitable terms, any public works, services and utilities, and to

develop any of the natural resources of the country, in so far as these

matters are not directly undertaken by the Administration. Any such

arrangements shall provide that no profits distributed by such agency,

directly or indirectly, shall exceed a reasonable rate of interest on

the capital, and any further profits shall be utilised by it for the

benefit of the country in a manner approved by the Administration.

Article 12.

The Mandatory shall be entrusted with the

control of the foreign relations of Palestine and the right to issue

exequaturs to consuls appointed by foreign Powers. He shall also be

entitled to afford diplomatic and consular protection to citizens of

Palestine when outside its territorial limits.

Article 13.

All responsibility in connection with the Holy

Places and religious buildings or sites in Palestine, including that of

preserving existing rights and of securing free access to the Holy

Places, religious buildings and sites and the free exercise of worship,

while ensuring the requirements of public order and decorum, is assumed

by the Mandatory, who shall be responsible solely to the League of

Nations in all matters connected herewith, provided that nothing in this

article shall prevent the Mandatory from entering into such

arrangements as he may deem reasonable with the Administration for the

purpose of carrying the provisions of this article into effect; and

provided also that nothing in this mandate shall be construed as

conferring upon the Mandatory authority to interfere with the fabric or

the management of purely Moslem sacred shrines, the immunities of which

are guaranteed.

Article 14.

A special commission shall be appointed by the

Mandatory to study, define and determine the rights and claims in

connection with the Holy Places and the rights and claims relating to

the different religious communities in Palestine. The method of

nomination, the composition and the functions of this Commission shall

be submitted to the Council of the League for its approval, and the

Commission shall not be appointed or enter upon its functions without

the approval of the Council.

Article 15.

The Mandatory shall see that complete freedom

of conscience and the free exercise of all forms of worship, subject

only to the maintenance of public order and morals, are ensured to all.

No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of

Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language. No person shall

be excluded from Palestine on the sole ground of his religious belief.

The right of each community to maintain its

own schools for the education of its own members in its own language,

while conforming to such educational requirements of a general nature as

the Administration may impose, shall not be denied or impaired.

Article 16.

The Mandatory shall be responsible for

exercising such supervision over religious or eleemosynary bodies of all

faiths in Palestine as may be required for the maintenance of public

order and good government. Subject to such supervision, no measures

shall be taken in Palestine to obstruct or interfere with the enterprise

of such bodies or to discriminate against any representative or member

of them on the ground of his religion or nationality.

Article 17.

The Administration of Palestine may organise

on a voluntary basis the forces necessary for the preservation of peace

and order, and also for the defence of the country, subject, however, to

the supervision of the Mandatory, but shall not use them for purposes

other than those above specified save with the consent of the Mandatory.

Except for such purposes, no military, naval or air forces shall be

raised or maintained by the Administration of Palestine.

Nothing in this article shall preclude the

Administration of Palestine from contributing to the cost of the

maintenance of the forces of the Mandatory in Palestine.

The Mandatory shall be entitled at all times

to use the roads, railways and ports of Palestine for the movement of

armed forces and the carriage of fuel and supplies.

Article 18.

The Mandatory shall see that there is no

discrimination in Palestine against the nationals of any State Member of

the League of Nations (including companies incorporated under its laws)

as compared with those of the Mandatory or of any foreign State in

matters concerning taxation, commerce or navigation, the exercise of

industries or professions, or in the treatment of merchant vessels or

civil aircraft. Similarly, there shall be no discrimination in Palestine

against goods originating in or destined for any of the said States,

and there shall be freedom of transit under equitable conditions across

the mandated area.

Subject as aforesaid and to the other

provisions of this mandate, the Administration of Palestine may, on the

advice of the Mandatory, impose such taxes and customs duties as it may

consider necessary, and take such steps as it may think best to promote

the development of the natural resources of the country and to safeguard

the interests of the population. It may also, on the advice of the

Mandatory, conclude a special customs agreement with any State the

territory of which in 1914 was wholly included in Asiatic Turkey or

Arabia.

Article 19.

The Mandatory shall adhere on behalf of the

Administration of Palestine to any general international conventions

already existing, or which may be concluded hereafter with the approval

of the League of Nations, respecting the slave traffic, the traffic in

arms and ammunition, or the traffic in drugs, or relating to commercial

equality, freedom of transit and navigation, aerial navigation and

postal, telegraphic and wireless communication or literary, artistic or

industrial property.

Article 20.

The Mandatory shall co-operate on behalf of

the Administration of Palestine, so far as religious, social and other

conditions may permit, in the execution of any common policy adopted by

the League of Nations for preventing and combating disease, including

diseases of plants and animals.

Article 21.

The Mandatory shall secure the enactment

within twelve months from this date, and shall ensure the execution of a

Law of Antiquities based on the following rules. This law shall ensure

equality of treatment in the matter of excavations and archaeological

research to the nationals of all States Members of the League of

Nations.

(1)

“Antiquity” means any construction or any product of human activity earlier than the year A. D. 1700.

(2)

The law for the protection of antiquities shall proceed by encouragement rather than by threat.

Any person who, having discovered an antiquity

without being furnished with the authorization referred to in paragraph

5, reports the same to an official of the competent Department, shall

be rewarded according to the value of the discovery.

(3)

No antiquity may be disposed of except to the

competent Department, unless this Department renounces the acquisition

of any such antiquity.

No antiquity may leave the country without an export licence from the said Department.

(4)

Any person who maliciously or negligently destroys or damages an antiquity shall be liable to a penalty to be fixed.

(5)

No clearing of ground or digging with the

object of finding antiquities shall be permitted, under penalty of fine,

except to persons authorised by the competent Department.

(6)

Equitable terms shall be fixed for

expropriation, temporary or permanent, of lands which might be of

historical or archaeological interest.

(7)

Authorization to excavate shall only be

granted to persons who show sufficient guarantees of archaeological

experience. The Administration of Palestine shall not, in granting these

authorizations, act in such a way as to exclude scholars of any nation

without good grounds.

(8)

The proceeds of excavations may be divided

between the excavator and the competent Department in a proportion fixed

by that Department. If division seems impossible for scientific

reasons, the excavator shall receive a fair indemnity in lieu of a part

of the find.

Article 22.

English, Arabic and Hebrew shall be the

official languages of Palestine. Any statement or inscription in Arabic

on stamps or money in Palestine shall be repeated in Hebrew and any

statement or inscription in Hebrew shall be repeated in Arabic.

Article 23.

The Administration of Palestine shall

recognise the holy days of the respective communities in Palestine as

legal days of rest for the members of such communities.

Article 24.

The Mandatory shall make to the Council of the

League of Nations an annual report to the satisfaction of the Council

as to the measures taken during the year to carry out the provisions of

the mandate. Copies of all laws and regulations promulgated or issued

during the year shall be communicated with the report.

Article 25.

In the territories lying between the Jordan

and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined, the

Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the Council of the

League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of such

provisions of this mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the

existing local conditions, and to make such provision for the

administration of the territories as he may consider suitable to those

conditions, provided that no action shall be taken which is inconsistent

with the provisions of Articles 15, 16 and 18.

Article 26.

The Mandatory agrees that, if any dispute

whatever should arise between the Mandatory and another member of the

League of Nations relating to the interpretation or the application of

the provisions of the mandate, such dispute, if it cannot be settled by

negotiation, shall be submitted to the Permanent Court of International

Justice provided for by Article 14 of the Covenant of the League of

Nations.

Article 27.

The consent of the Council of the League of Nations is required for any modification of the terms of this mandate.

Article 28.

In the event of the termination of the mandate

hereby conferred upon the Mandatory, the Council of the League of

Nations shall make such arrangements as may be deemed necessary for

safeguarding in perpetuity, under guarantee of the League, the rights

secured by Articles 13 and 14, and shall use its influence for securing,

under the guarantee of the League, that the Government of Palestine

will fully honour the financial obligations legitimately incurred by the

Administration of Palestine during the period of the mandate, including

the rights of public servants to pensions or gratuities.

The present instrument shall be deposited in

original in the archives of the League of Nations and certified copies

shall be forwarded by the Secretary-General of the League of Nations to

all members of the League.

Done at London the twenty-fourth day of July, one thousand nine hundred and twenty-two.

Certified true copy:

For the Secretary-General,

RAPPARD,

Director of the Mandates Section.

Geneva, September 23, 1922

Territory known as Trans-Jordan

Note by the Secretary-General

The Secretary-General has the honour to

communicate for the information of the Members of the League, a

memorandum relating to Article 25 of the Palestine Mandate presented by

the British Government to the Council of the League on September 16th,

1922.

The memorandum was approved by the Council

subject to the decision taken at its meeting in London on July 24th,

1922, with regard to the coming into force of the Palestine and Syrian

mandates.

Memorandum by the British Representative

1. Article 25 of the Mandate for Palestine provides as follows:

“In the territories lying

between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately

determined, the Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the

Council of the League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of

such provision of this Mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the

existing local conditions, and to make such provision for the

administration of the territories as he may consider suitable to those

conditions, provided no action shall be taken which is inconsistent

with the provisions of Articles 15, 16 and 18.”

2. In pursuance of the provisions of this Article, His Majesty’s Government invite the Council to pass the following resolution:

“The following provisions of

the Mandate for Palestine are not applicable to the territory known as

Trans-Jordan, which comprises all territory lying to the east of a line

drawn from a point two miles west of the town of Akaba on the Gulf of

that name up the centre of the Wady Araba, Dead Sea and River Jordan to

its junction with the River Yarmuk; thence up the centre of that river

to the Syrian Frontier.”

Preamble. - Recitals 2 and 3.

Article 2.-The words “placing the country

under such political administration and economic conditions as will

secure the establishment of the Jewish national home, as laid down in

the preamble, and.”

Article 4.

Article 6.

Article 7. - The sentence “The shall be

included in this law provisions framed so as to facilitate the

acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take up their

permanent residence in Palestine.”

Article 11. - The second sentence of the first paragraph and the second paragraph.

Article 13.

Article 14.

Article 22.

Article 23.

----

In the application of the Mandate to

Trans-Jordan, the action which, in Palestine, is taken by the

Administration of the latter country, will be taken by the

Administration of Trans-Jordan under the general supervision of the

Mandatory.

3. His Majesty’s Government accept full

responsibility as Mandatory for Trans-Jordan, and undertake that such

provision as may be made for the administration of that territory in

accordance with Article 25 of the Mandate shall be in no way

inconsistent with those provisions of the Mandate which are not by this

resolution declared inapplicable.

1. To those colonies and territories which as a consequence of the

late war have ceased to be under the sovereignty of the States which

formerly governed them and which are inhabited by peoples not yet able

to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern

world, there should be applied the principle that the well-being and

development of such peoples form a sacred trust of civilization and that

securities for the performance of this trust should be embodied in this

Covenant.

2. The best method of giving practical effect

to this principle is that the tutelage of such peoples should be

entrusted to advanced nations who by reason of their resources, their

experience or their geographical position can best undertake this

responsibility, and who are willing to accept it, and that this tutelage

should be exercised by them as Mandatories on behalf of the League.

3. The character of the mandate must differ

according to the stage of the development of the people, the

geographical situation of the territory, its economic condition and

other similar circumstances.

4. Certain communities formerly belonging to

the Turkish Empire have reached a stage of development where their

existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized,

subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a

Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of