In early 2019, a handful of progressive Democrats galvanized their

party around a set of ideas that—even if only partially

implemented—would restructure vast areas of the American economy and

radically refashion the American household with large and ongoing

costs.

This set of proposals, called the Green New Deal (GND)—introduced in the 116

th

Congress as H. R. 109 and S. 59—has earned attention, depending on the

source of commentary, either as an instrument of effective leadership

for the 21

st century or as an unserious ideological signaling

exercise. In either case, it is difficult to read as a set of genuine

policy proposals; it is perhaps better described as a far-reaching,

aspirational set of guideposts for a resurgent progressive force in

American politics.

[1]

The GND actually has a long progressive pedigree. It was championed

by statewide and national Green Party candidates for governor and

president as early as 2006. Presidential candidate Jill Stein gave it

prominence in 2012. The GND attracted early attention from scores of

Democrats including nine presidential candidates and 12 United States

Senators. In response, Republicans pushed for a vote on the GND in the

Senate that failed to attract a single vote from Democrats, including

the resolution’s 12 cosponsors.

[2]

While this paper focuses on the energy components of the GND, among

other features, the GND would guarantee “a job with a family-sustaining

wage, adequate family and medical leave, paid vacations, and retirement

security” as well as high-quality health care, affordable and safe

housing, affordable food, and access to nature. In a word, it promises a

utopia.

At its root, the Green New Deal is a radical blueprint to

de-carbonize the American economy. Carbon—whether contained in wood,

coal, gas, or oil—is a byproduct of burning fuel. Eliminating these

energy sources would have massive ramifications for the economy.

Regardless of its authors’ intentions, our aim here is to examine the

relative trade-offs associated with taking significant portions of the

GND seriously. What would it actually mean to implement significant

portions of proposal? Can we understand the effects at a household level

in different regions of the country?

To that end, the following analysis examines the transformation of

electricity production, transportation and elements of shipping, as well

as construction in five representative states that implementation of

the GND would necessitate. It requires a considerable number of

assumptions that we share in order to allow the reader to come to his or

her own conclusions about the merits of the GND compared to alternative

uses of scarce societal resources.

The sum of our analysis is not favorable for the GND’s advocates. At

best, it can be described as an overwhelmingly expensive proposal

reliant on technologies that have not yet been invented. More likely,

the GND would drive the American economy into a steep economic

depression, while putting off-limits affordable energy necessary for

basic social institutions like hospitals, schools, clean water and

sanitation, cargo shipments, and the inputs needed for the production

and transport of the majority of America’s food supply.

We do not include in this analysis estimates of the cost of the

non-energy components of the GND. Those costs might dwarf the

energy-related costs by an order of magnitude.

For each of five states, we provide a range of estimated costs as well as a best estimate.

Findings

At a minimum, the GND would impose large and recurring costs on American households.

[3]

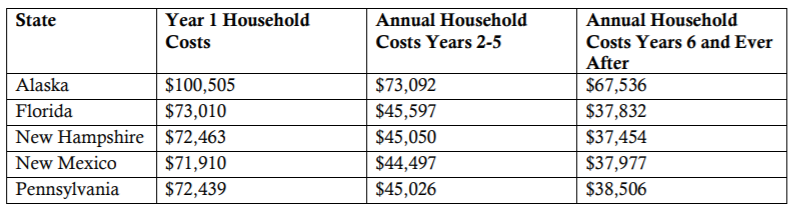

We conclude that in four of the five states analyzed—Florida, New

Hampshire, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania—the GND would cost a typical

household more than $70,000 in the first year of implementation,

approximately $45,000 for each of the next four years, and more than

$37,000 each year thereafter. In Alaska, estimated costs are much

higher: more than $100,000 in year one, $73,000 in the subsequent four

years, and more than $67,000 each year thereafter.

Sum of Household Costs

Methodology

While the Green New Deal is a wide-ranging proposal, it ultimately

amounts to an imposition of a significant set of constraints on the

energy sector. At present, Americans consume energy from many different

resources. In general, fossil fuels and some renewable fuels directly

power most transportation, and much of the equipment in the industrial,

commercial, and household sectors. The GND would likely reduce the net

energy consumption by these sectors while shifting all energy demand

either to the electric grid or toward self-contained renewable sources

like solar panel arrays designed to power particular units.

Implementation of the GND would shift energy consumption entirely to

electric current from today’s primary sources, including fossil fuels.

Benjamin Zycher of the American Enterprise Institute has analyzed the cost of electricity under the GND.

[4]

His study looks at current electricity generation and estimates what it

would cost to replace all non-GND compliant electricity generation—such

as coal, natural gas, petroleum, and nuclear—with wind and solar power.

Zycher also looks at the cost of emissions, transmission, backup power,

and land for the replacement capacity.

Zycher’s analysis is understated because it does not calculate

additional demand for electricity—the dynamic effects of policy

changes—that would obtain as a result of GND implementation. Zycher’s

low-end estimate addresses the transformation of current power

generation to GND power. Of course, other provisions of the GND would

generate significant demand increases. In addition, Zycher’s cost

estimates extend indefinitely and would affect American households far

into the future.

Energy research firm Wood Mackenzie estimates that the greening of

the U.S. power sector would cost approximately $35,000 per household and

take 20 years.

[5]

Wood Mackenzie estimate a total price tag of some $4.7 trillion,

including around $1.5 trillion to add 1,600 gigawatts of wind and solar

capacity and $2.5 trillion of investments in 900 gigawatts of storage.

Another $700 billion is estimated for new high transmission power lines

to move that electricity from sun-drenched deserts and windswept plains

to the urban areas where it would be used.

Most provisions of the GND are so broad and open-ended that the list

of potential programs necessary to implement the program is limited by

the capacity of legislators to imagine a new government program.

Therefore, it is impossible to calculate the whole or maximum cost of

the GND. However, other parts of the GND are more precise, sufficiently

so that an approximate minimum cost estimate is available.

In addition to increased costs due to electric generation compliant with the GND renewable mandate, the GND calls for:

- The elimination of “pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from

the transportation sector as much as is technologically feasible;”

- “[U]pgrading all existing buildings in the United States and

building new buildings to achieve maximal energy efficiency, water

efficiency, safety, affordability, comfort, and durability, including

through electrification;”[6]

- Where technologically feasible, the elimination of the use of

fossil fuels and other combustible, greenhouse gas-emitting energy

sources.

This study evaluates the estimated cost of the GND in four specific categories across five model states. The categories are:

- Additional electricity demand;

- Costs associated with shipping and the logistics industry;

- New vehicles; and

- Building retrofits.

These cost estimates were made with the available data and

analysis. However, they are only low-end approximations given the

unprecedented scope of the GND. A key source, in addition to Zycher’s

analysis, was produced in early 2019 by Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Dan

Bosch of the American Action Forum.

[7]

Of interest for our analysis, Holtz-Eakin and Bosch estimate the costs

of a “low-carbon electricity grid” (at $5.4 trillion versus Zycher’s

$8.95 trillion annual expenditures) as well as the costs of a

zero-emission transportation system, and a national policy for “green

housing.”

Taken together and married to our own analysis, these estimates

develop a floor of expectations for the costs associated with the

implementation of the GND in the near and intermediate term.

The five selected states demonstrate diverse climates, geography, economies, and populations.

- Alaska is a remote, sparsely populated, and cold state.

- Florida is one of the largest states in terms of population and

economy, undoubtedly the economic powerhouse of the Southeast, in a warm

climate.

- New Hampshire is a small state that is well connected with larger economies in the region in a cold climate.

- New Mexico is a small state in terms of population, but large

geographically, is generally warmer, and is situated between significant

large states by all metrics.

- Pennsylvania is a large state in terms of geography, economy, and

population in a mild-colder climate and is well integrated with the

largest regional economy in the United States.

Previous Analysis

Evaluating the impact of the GND in these states will provide a

glimpse into the proposal’s broader national impact and information

similar states can use to infer their own cost estimates.

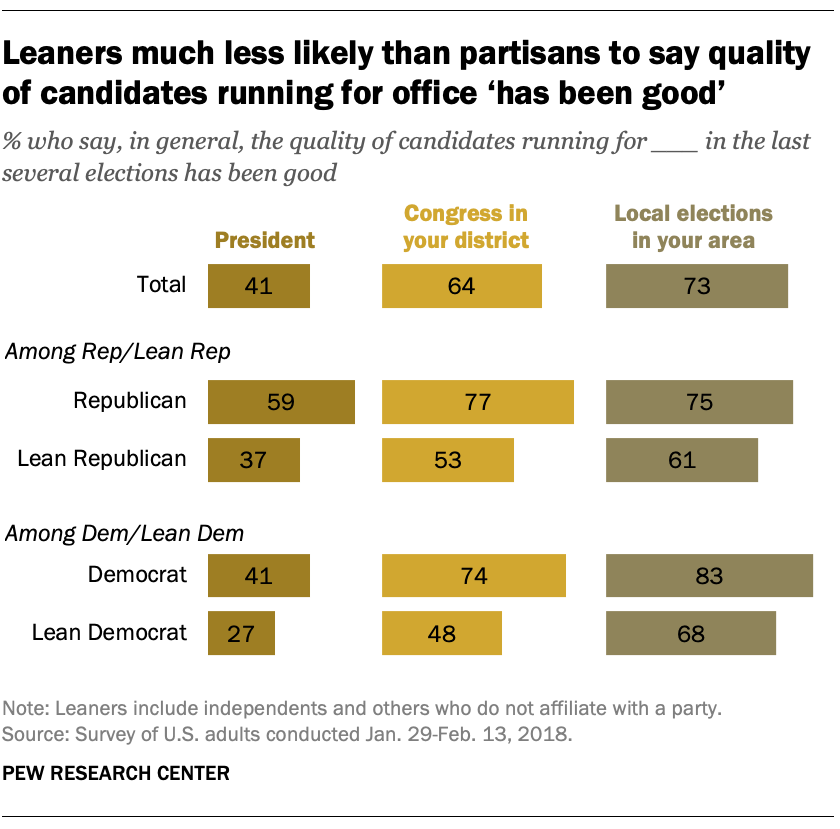

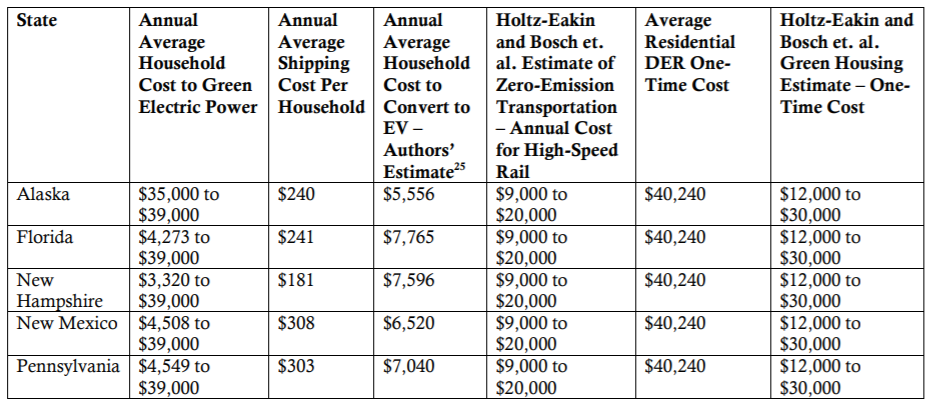

As shown in Figure 1, earlier analyses provide a range of new, annual

costs expected for each household in each of our states from a low-end

$24,820 in New Hampshire to upward of $89,000 in all our states. These

estimates cover only three aspects of the GND proposals and do not

include the dynamic effects of increased demand on the power grid, for

example, from a fleet of electric cars or the transformation of all

automobiles to zero-emission vehicles.

The cost estimates for the power grid and transportation system do

not include the costs necessary to replace or retrofit machinery

currently dependent on fossil fuels or other combustibles. Such an

estimate would require an inventory of every machine of this type in the

country, from propane-powered forklifts to natural gas stoves to

diesel-powered tugboats, as well as cost estimates of all replacement

technology capable of being indirectly powered by wind and solar and

necessary to achieve parity in terms of their ability to perform the

same work. Therefore, not counted in this analysis are road-building and

maintenance equipment, tractors and other farm equipment, or the

standard tools of heavy construction for, among other things, new

buildings, windmills, solar and other alternative energy facilities.

Figure 1. Previous Estimates Produce Range of New Annual Household Costs –

Electric Power, Transportation, Housing [8][9]

Shipping and Logistics

Shipping and Logistics

Modern America is reliant upon global, hemispheric, and regional

trade. Local economies (beyond a handful of experimental communities)

exchange goods and services. We build, dig, grow, and ultimately ship

things and it requires a great deal of energy to do so.

An estimate for the cost of the GND proposals on shipping and

logistics starts with data on goods shipped to each of the model states

by transportation methods for which we have data. However, basic

economic theory suggests that due to increased costs for GND-compliant

shipping, an elasticity of demand would reduce the use of these

technologies, as higher prices drive away consumers. While this could

inflate our estimates, we are confident that the costs for development

and deployment of substitute shipping technologies far outweigh reduced

demand for traditional shipping even after the expense of retrofitting

it to the GND.

Our estimates exclude air cargo and relies exclusively on trucking,

rail, and barge traffic for which data are available. The exclusion of

air cargo would effectively eliminate the availability of off-season

produce, the timely delivery of FedEx and Amazon packages and a great

deal of U.S. mail delivery. Relative comparisons are made between

current costs and estimated GND compliant costs by evaluating energy

intensity of the total shipping in terms of BTUs.

[10]

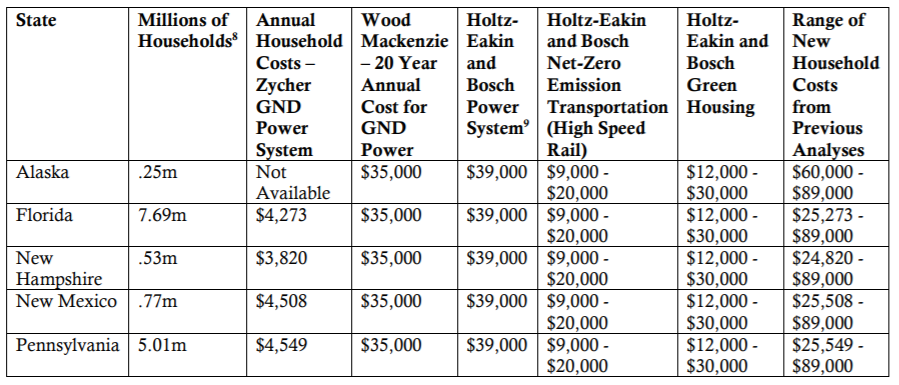

The Center for Transportation Analysis’s Freight Analysis Framework

database provides information on total ton-miles of freight by shipping

mode by destination state.

[11] These ton-miles also exclude any freight that is not GND-compliant, such as shipments of oil or coal.

Figure 2. Mode-Exclusive Million Ton-Miles by Destination State by Mode, Excluding Non-GND Compliant Freight (2017)

The BTU intensity per ton-mile for trucking, rail, and barge traffic is drawn from an analysis by the U.S. Department of Energy.

[12]

Trucking is approximately four to five times as energy intensive as

rail or barge (1,390 BTU per ton-mile for trucking versus 320 and 225

for rail or barge.)We assume that nearly all freight delivered to these

states is through a combination of these modes or via air cargo.

However, air cargo is not specified in the available data and therefore

we assume no costs for bringing air cargo shipments into compliance with

the GND. As a result, the cost estimates presented here are

significantly lower than the likely costs.

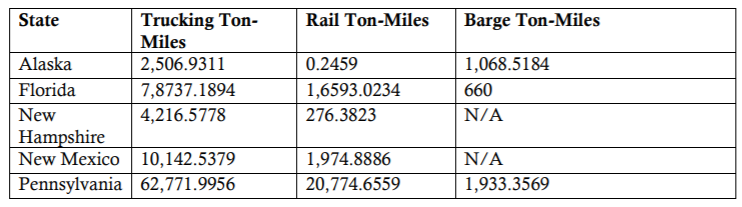

The combination of ton-miles in Figure 2 with BTU intensity by mode

gives us an estimate for the total annual energy consumption, in BTUs,

for freight delivered to each model state for each mode of shipping.

Figure 3, relying upon an estimate from the University of Pennsylvania

for $32.24 for the production of a million BTUs from renewable sources,

provides an estimate for increased shipping fuel costs due to GND

implementation.

[13]

For purposes of illustration, we assume an extraordinary technological

improvement in the development of renewable energy and have halved the

cost estimate of a million BTUs to $16.12.

Figure 3. Mode-Exclusive Shipping Energy Consumed in Million BTUs (2017) and Annual Household Costs

New Vehicles

New Vehicles

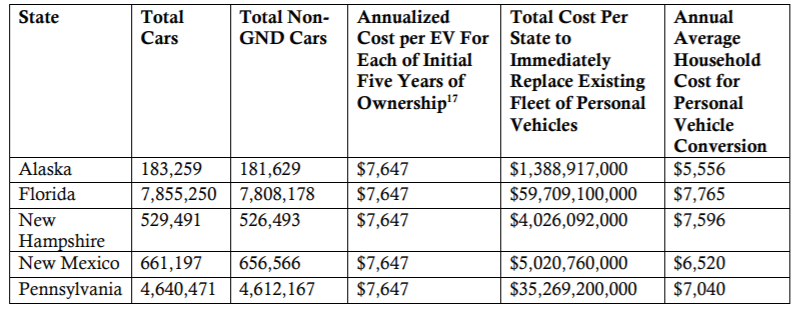

A key pillar of the GND is replacing all existing combustible-powered

vehicles with electric vehicles (EVs). Current projections are for EVs

to be, on average, more costly than conventional vehicles. EV prices,

like conventional gas vehicle prices, will also vary based on size and

features. Perhaps the most critical differentiating feature for the near

term is the type of battery available for the vehicle. EVs that charge

faster and have a longer range will undoubtedly fetch higher market

prices. However, for the purposes of our analysis, a conservative

estimate for EV costs to consumers is used. The price of $39,500 is in

line with the base MSRPs of the most popular EVs sold today.

[14] To control for existing EVs, a ratio of 2.21 EVs per 1,000 residents is used to calculate total EVs in each state.

[15]

Commercial cargo trucks are a different matter. There has not yet

been similar adoption of EV technology in trucking. Further, prices of

EV trucks are largely speculative at this time. For illustrative

purposes (though not included in our analysis or conclusions), the

prospective list price of an electric semi-tractor from Tesla is

$180,000.

[16]

Needless to say, this price is speculative and in these five states

there are more than 15 million commercial trucks on the road today.

While the economic effects of the GND must account for commercial

vehicles, our analysis does not include them, and is therefore a

conservative estimate of new vehicle costs. However, a partial

accounting is made for truck freight in the shipping analysis above.

These costs are just upfront purchase price seen by consumers. EVs

will also impose costs through the necessary infrastructure retrofits to

have sufficient charging capacity for these vehicles at homes,

businesses, and other public places, each of which will cost many

thousands of dollars.

Figure 4. Annual Cost of Replacing Existing non-GND Compliant Vehicles with Electric Vehicles [17]

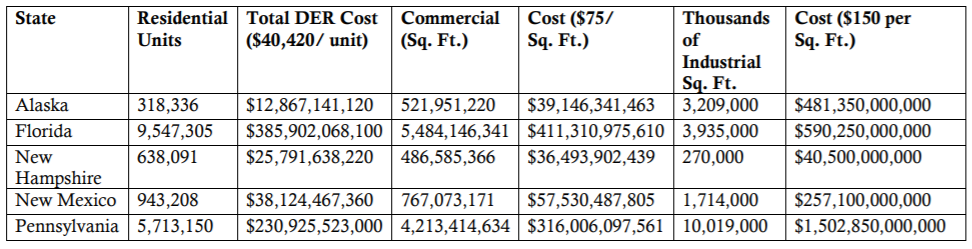

The GND calls for maximum building efficiency. It explicitly

envisions the retrofit of the current stock of structures in America. In

the construction industry, retrofits of this kind are known as deep

energy retrofits (DERs). The cost of a DER can vary considerably, given

varying climates, building ages, uses, sizes, and other factors. A 2014

meta-analysis relied upon by the Department of Energy is the basis for

our assumptions about residential construction. The average cost per a

unit of housing for a DER is estimated at $40,420.

[18] The maximum average cost of a DER for commercial buildings is estimated at $75 per square foot.

[19]

Building Retrofits

Almost no data are readily available regarding industrial DERs, so we

rely upon assumptions made in the underlying analyses. Therefore, we

use an average maximum cost for large commercial buildings, $150 per

square foot, as an estimated cost for industrial DERs.

[20]

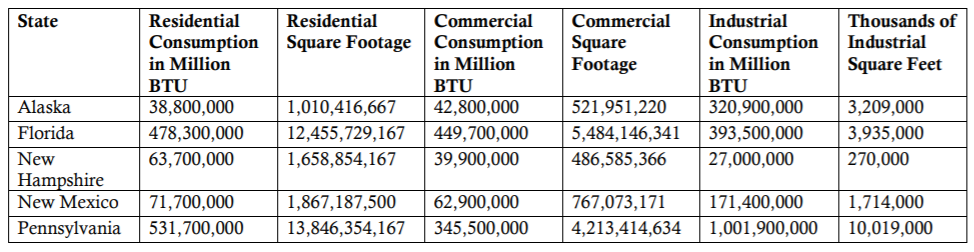

State-by-state data for total building square footage is also scarce.

For this study, energy consumption totals per sector divided by average

energy consumption per square foot, both in BTUs, determined total

square footage in each model state. Consumption per square foot was not

readily available for industrial buildings, so a modest increase in

consumption per square foot was assumed over commercial buildings in

order to derive total industrial square footage.

Data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) show that

energy consumption per square foot in 2015 was 38,400 BTUs for

residences and 82,000 BTUs for commercial buildings.

[21]

Industrial consumption per square foot was assumed at 100,000 BTUs,

given the increase in BTU consumption per square foot from residential

to commercial.

Combining these figures with total 2016 energy consumption in BTUs per sector, obtained from EIA’s state-by-state database,

[22] produced estimates of total active square footage of buildings across all sectors.

Figure 5. Residential, Commercial, and Industrial Square Footage[23]

Figure 6. DER Investments under GND

Figure 6. DER Investments under GNDThe

total cost of implementing a DER for all existing buildings in the

United States is estimated via two methods. For residential, total DER

cost is calculated by obtaining census data on total housing units in

each state in 2018 and multiplying this figure by the average

residential unit DER cost of $40,420.

[24]

For commercial and industrial buildings, the average DER cost is

obtained by multiplying estimated and assumed DER costs for commercial

and industrial buildings, respectively, by total estimated square

footage.

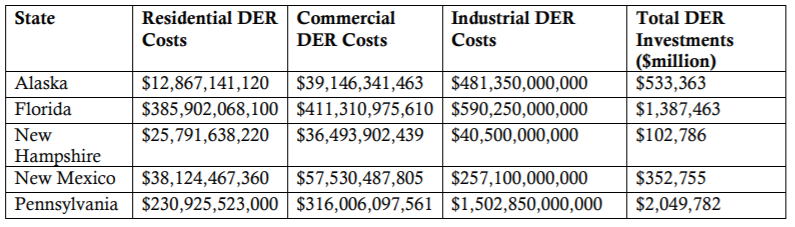

Taken together, the estimated costs for retrofitting current

residential, commercial, and industrial buildings is astronomical. Of

our representative states, Alaska has the fewest residential structures

and other square footage by orders of magnitude.Critically, the

discussion of this paper is about the cost of transition to GND

structures. Clearly, any benefits realized from more energy efficient

buildings would reduce future operating costs and emissions.

Yet, the combined investments to upgrade residential, commercial, and

industrial building stock is a mind-boggling $533.4 billion. (See

Figure 7.) Therefore, for the purposes of public education, the key

figure is the average cost of a DER for residential homes, $40,420.

Figure 7. Total DER Investments by Household

Summary and Synthetic Estimates for Robustness

Summary and Synthetic Estimates for Robustness

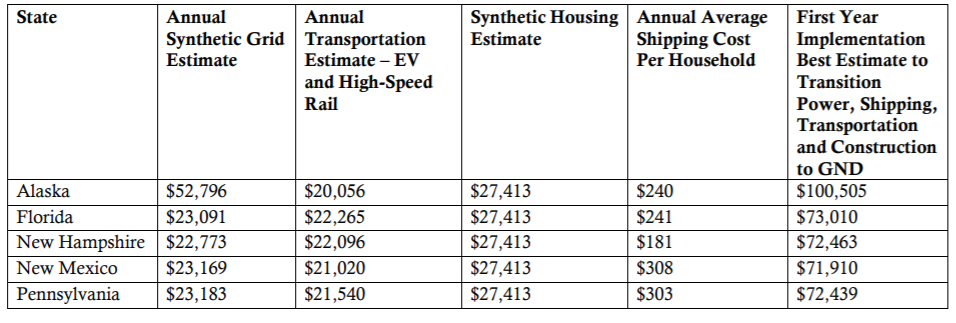

Figures 8, 9, and 10 summarize the findings of this study in order to

put in context the tremendous costs of the GND. As a final set of

calculations, we created synthetic estimates for the variables where

multiple analyses exist: the household costs for the electric grid,

electric vehicles, and retrofitting the nation’s housing stock to comply

with the GND.

Zycher’s analysis varies by state for the electric grid, while

Holtz-Eakin and Bosch offer a national average of $39,000 and Wood

Mackenzie finds a national average of $35,000. The first synthetic

variable, Synthetic Grid Estimate, takes the average of these three

figures. For Alaska, only the latter two estimates are averaged; Zycher

did not offer an estimate. For example, in Florida, Zycher estimates

$4,273, Wood Mackenzie estimates $35,000, and Holtz-Eakin and Bosch

estimate $39,000. The average or combined estimate is the sum of the

figures divided by three, $23,091.

We present our own estimate to transform the auto fleet to EVs and

include a range of likely expenses from Holtz-Eakin and Bosch for

shifting the nation to high-speed rail. The synthetic transportation

estimate is the mid-point of the range for high-speed rail combined with

the household EV costs.

We also created a synthetic estimate for housing using the average

DER cost of $40,240 and the range of likely outcomes found by

Holtz-Eakin and Bosch of $12,000 to $30,000. Because there is no state

variability in the data, the synthetic housing estimate is $27,413.

Figure 8. Average Household Costs [25]

The synthetic estimates, when combined with the estimate for

increased shipping expenses, produce a single figure for households in

each state for the initial year of implementation. For each of the next

four years, the household costs would fall by $27,413, the amount to

implement a DER for every home. After five years, the expense associated

with converting each household to EVs would fall away.

While it is not possible to express absolute confidence in the

estimated costs for these provisions of the GND, the use of synthetic

estimates reduces the risk of any one type of analysis skewing the

results. Critics will undoubtedly highlight the variance in the data.

However, variance is not a detriment when analyzing such a sweeping set

of proposals. Rather, it is a mark of humility. Further, we contend that

the conclusions drawn here are extremely modest, representing only the

energy-related costs. The GND calls for universal health care and

guaranteed employment among other social policies that would have

tremendous transition costs.

Figure 9. Synthetic Estimates and Best Estimate of Household Costs

Figure 10. Sum of Average Household Costs

Figure 10. Sum of Average Household Costs

Conclusion

Conclusion

The Green New Deal is a plan to radically reshape the American

economy and the landscape of a household economy. Every aspect of how we

live and work would be affected by the proposal. The preponderance of

goods essential for agriculture, transportation, and construction would

be replaced. In short, it is not realistic. However, national political

figures and perhaps even a growing movement of fellow citizens would

like to implement it as a policy agenda.

All of the potential benefits, and social costs—such as massive

increases in land use for the production of energy and food without

fossil fuel inputs—are beyond the scope of this analysis. Yet we can

conclude that the Green New Deal is an unserious proposal that is at

best negligent in its anticipation of transition costs and at worst is a

politically motivated policy whose creativity is outweighed by its

enormous potential for economic destruction.

Notes

[1] Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal, H.R. 109/S. 59, 116

th

Congress,

https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/109/text,

https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-resolution/59?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22green+new+deal%22%5D%7D&s=2&r=3.

[2] Vote summary, “On the Cloture Motion (Motion to Invoke Cloture on the Motion to Proceed to S.J. Res. 8 ,

Vote Number 52, 3/5 Vote Result: Cloture Motion Rejected March 26, 2019, 04:18 PM,

https://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=116&session=1&vote=00052#top.

[3]

Benefit-cost estimates rely on net present value (NPV) to provide

analysts a tool to see how various benefits or costs change over time.

Similarly, robust cost estimates utilize NPV analysis and costs are

calculated as negative, future cash-flows. The various elements of the

GND – from changes in housing stock, to vehicles, to the electric grid –

would all require specialized and differing discount rates to find the

NPV. This analysis is a composite of others’ work as well as our own

estimates and there is no single discount rate available that is

sensible for either the component parts of the GND or the other cost

estimates. As a result, we did not discount future costs. Admittedly,

this may overestimate the effects of the GND in the out years but we are

confident that the magnitude of the estimated costs are not affected by

minor variances in discount rates or the NPV for the GND.

[4] Benjamin Zycher,

The Green New Deal: Economics and Policy Analytics, American Enterprise Institute, 2019, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/RPT-The-Green-New-Deal-5.5x8.5-FINAL.pdf.

[5]

Nichola Groom, “Weaning U.S. power sector off fossil fuels would cost

$4.7 trillion: study,” Reuters, June 27, 2019,

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-carbon-report/weaning-u-s-power-sector-off-fossil-fuels-would-cost-4-7-trillion-study-idUSKCN1TS0GX.

[6] H.R.109.

[7]

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, Dan Bosch, Ben Gitis, Dan Goldbeck, and Philip

Rossetti, The Green New Deal: Scope, Scale, and Implications, American

Action Forum, February 25, 2019,

https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-green-new-deal-scope-scale-and-implications/.

[8]

With 126.22 million households in the United States in 2017. “Number of

households in the United States in 2017, by state (in millions),”

Statista,

https://www.statista.com/statistics/242258/number-of-us-households-by-state/.

[9] Holtz-Eakin and Bosch provide national estimate and an average household estimate. Presented here is the household estimate.

[10] A British thermal unit is a unit of measure for energy. One million BTUs is enough to dry about 50 loads of laundry.

[11]

Freight Analysis Framework Data Tabulation Tool (FAF4), Center for

Transportation Analysis, accessed July 10, 2019,

https://faf.ornl.gov/faf4/Extraction2.aspx.

[12]

Trucking and Rail BTUs per ton-mile: U.S. Department of Energy, Office

of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, “Freight Transportation

Demand: Energy-Efficient Scenarios for a Low-Carbon Future,”

Transportation Energy Futures Series, March 2013,

https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc844590/m2/1/high_res_d/1072830.pdf.

Barge BTUs per ton-mile: U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of

Transportation Statistics, Table 6-10 Energy Intensities of Domestic

Freight Transportation Modes: 2007-2013,

https://www.bts.gov/archive/data_and_statistics/by_subject/freight/freight_facts_2015/chapter6/table6_10.

[13]

Energy Cost Calculator, College of Agricultural Sciences, Cooperative

Extension, Pennsylvania State University, accessed July 10, 2019,

https://buffalo.extension.wisc.edu/files/2011/01/Energy-Cost-Calculator-for-Various-Fuels-PSU.pdf.

[14]

Jeffrery Rissman, “The Future of Electric Vehicles in the U.S.,” Energy

Innovation Policy & Technology LLC, September 2017,

https://energyinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017-09-13-Future-of-EVs-Research-Note_FINAL.pdf.

[15]

Mark Kane, “State-By-State Look at Plug-In Electric Cars per 1,000

Residents,” InsideEVs, December 1, 2018,

https://insideevs.com/news/341522/state-by-state-look-at-plug-in-electric-cars-per-1000-residents/.

[16] Tesla Semi, Tesla website, accessed July 10, 2019, https://www.tesla.com/semi.

[17]

The cost of an EV purchased for $39,500 can be amortized across five

years with a typical low interest auto loan. We assume that each auto is

purchased with ten percent down ($3,950) and $35,550 on credit at 2.9

percent. This generous formula creates an annual burden, in addition to

the down payment, of $637.21 a month or nearly $7,647 a year. To

simplify the analysis, we assume that the down payment is provided

through a combination of new federal and state subsidies, and thus

consumers are responsible for 90 percent of the purchase price.

[18]

Brennan Less and Iain Walker, “A Meta-Analysis of Single-Family Deep

Energy Retrofit Performance in the U.S.”, Environmental Energy

Technologies Division, Berkeley Lab, prepared for the U.S. Department of

Energy

Office of Scientific and Technical Information, 2014, https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1129577.

[19]

Daniel S.Bertoldi, “Deep Energy Retrofits Using the Integrative Design

Process: Are they Worth the Cost,” Master’s Projects and Capstones,

University of San Francisco, spring 2014,

https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/22.

[20] Ibid.

[21]

Energy Information Administration, Table CE1.1 Summary annual household

site consumption and expenditures in the U.S.—totals and intensities,

2015,” May 2018,

https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2015/cande/pdf/ce1.1.pdf.

Energy Information Administration, Table E2. Major fuel consumption

intensities (Btu) by end use, 2012, May 2016

https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/data/2012/cande/pdf/e2.pdf.

[22]

Energy Information Administration, Alaska End-use energy consumption

2017, estimates, accessed July 10, 2019,

https://www.eia.gov/beta/states/states/ak/overview.

[23]

Figure 5 relies upon 2016 consumption data found at the EIA’s website.

Energy Information Administration, State Energy Consumption Estimates:

1960 through 2017,

https://www.eia.gov/state/seds/sep_use/notes/use_print.pdf.

[24] U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts, Alaska, accessed July 10, 2019, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/AK.

U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts, Florida, accessed July 10, 2019, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/FL/PST045218

U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts, New Hampshire, accessed July 10,

2019, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NH/LND110210.

U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts, New Mexico, accessed July 10, 2019, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM.

U.S. Census Bureau, QuickFacts, Pennsylvania, accessed July 10, 2019, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PA.

[25] These costs are for each of the first five years.