Covid curbs 400th Mayflower anniversary as Americans stay away

Gifts and art mark event but representatives of indigenous Wampanoags who suffered due to colonialism were not present

First published on Wed 16 Sep 2020 11.36 EDT

There was some pomp and ceremony. A military band played, ambassadors and civic leaders made speeches, and the union flag fluttered beside the stars and stripes of the US close to the spot where, exactly 400 years ago, the Mayflower set sail.

But there was also a sense of melancholy around the event on the harbourside at Plymouth on Wednesday. The many thousands of Americans who had been expected to arrive in the Devon city for the 400th anniversary of the pilgrims’ voyage were absent due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Perhaps more importantly, there was no representation of the Wampanoag nation, the indigenous people who suffered disease and war in the decades after the arrival of what is now the US. Some of them have been involved in many of the events and projects that were scheduled to be held to commemorate the anniversary, but none were present at the waterside on Wednesday.

Charles Hackett, the chief executive of Mayflower 400, acknowledged it was sad that Covid-19 had stopped Americans and members of the Wampanoag nation attending. “For obvious reasons they couldn’t be here,” he said. “But the commemoration was never about a single event on a single day. The history is too complex for that.”

The dignitaries, including the US ambassador to the UK, Woody Johnson, were in the city to mark the day and name a new Mayflower, a small, sleek autonomous research ship that will gather information from the oceans.

It was launched from close to the refurbished Mayflower monument (with the help of a bottle of Plymouth gin) and then headed out into Plymouth Sound, following a similar course to the one the pilgrims took four centuries ago.

The ship passed one of the key works of art for Mayflower 400, an installation on Mount Batten Breakwater spelling out the phrase in six-metre high letters: “No New Worlds”.

The sculpture, by the artist collective Still/Moving and called Speedwell (the name of the Mayflower’s companion ship) is seen as both a comment on the voyage of the pilgrims – they weren’t heading for the “New World”, but rather sailing towards one that had been home to people for many millennia – and a reminder that there is no other planet for humans to flee to if Earth is not looked after.

Visitors have been adding their own messages to the artwork about saving the planet, and about racial and sexual equality.

One of the artists, Martin Hampton, said the Mayflower story was “sensitive and raw” for many people in the US. “As English people, we can feel insulated from it. It’s something that happened over in America. But this commemoration in Plymouth should bring home that this process of colonisation is live. Indigenous people of North America are still suffering because their land was stolen or is under threat.”

The day of the sailing – 16 September – was due to be at the heart of a series of commemorative events in Plymouth ranging from community plays to “occupations” of public space in the city led by a Native American artist.

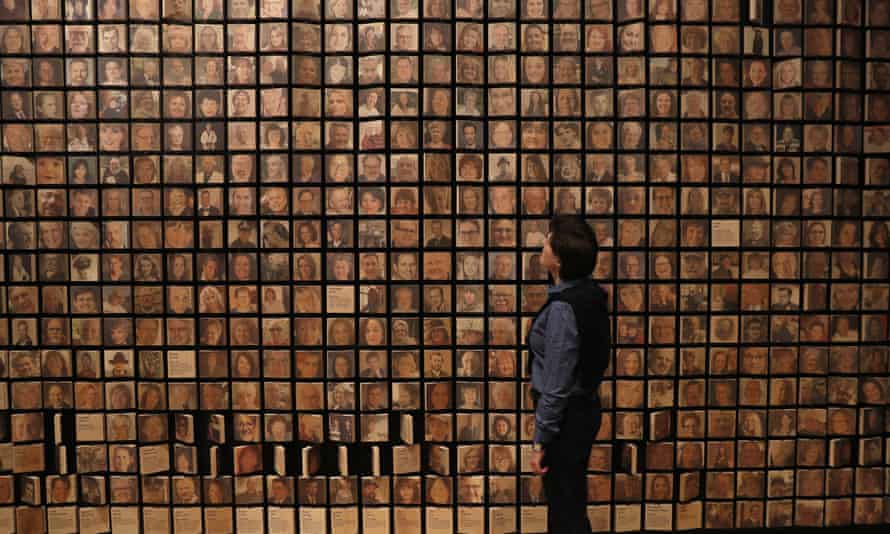

Some events are still ongoing. An exhibition featuring an ornate wampum (shell bead) belt created by more than 100 Wampanoag people is touring the UK.

The story of the Mayflower and its impact is to be told in a major exhibition at the Box, a new art gallery and museum opening at the end of the month. A new Antony Gormley sculpture was to be craned into place on Wednesday and other rescheduled events will run until next summer.

Away from the pomp, Plymouth people expressed sadness that the commemoration had been so affected by Covid. Karen Murphy, who works in the Mayflower 400 souvenir shop, said she was sad to see the streets so empty but, despite Covid, its T-shirts, hoodies, mugs and fridge magnets were selling steadily. “I think a lot are being sent to the US,” she said.

In the Harbourside fish and chip shop, owner Kelvin Horton said he didn’t think many people in Plymouth grasped the trickiness of the Mayflower story. He said: “I hope this sort of day will make people think about it.”

Three thousand miles away in Massachusetts, Paula Peters, a member of the Wampanoag nation who sits on an advisory committee that has helped shape the UK commemorations, said that despite her involvement, she would not be marking 16 September.

“The Wampanoag have been marginalised for centuries, so the acknowledgment at this time is long overdue,” she said. “The Mayflower story is one that honestly cannot be told without the inclusion of the Wampanoag perspective.

“But I have no intention of marking the anniversary – 16 September has no significance to the Wampanoag. It is just another day here.”