Mayflower 400: how the pilgrims coped with separation

Those who emigrated on the Mayflower in 1620 seeking religious liberty might not have realised the challenges that lay ahead of them. Roaring summer heat and bitter winters were only part of their test. Economic instability, disease and troubling encounters with the native population meant that the early years of the Plymouth colony were tarnished by hardship.

However, it was not only material and environmental adversity that faced the colonists or their friends and families back home. The distance stretching between those who stayed and those who sailed was felt painfully and persistently.

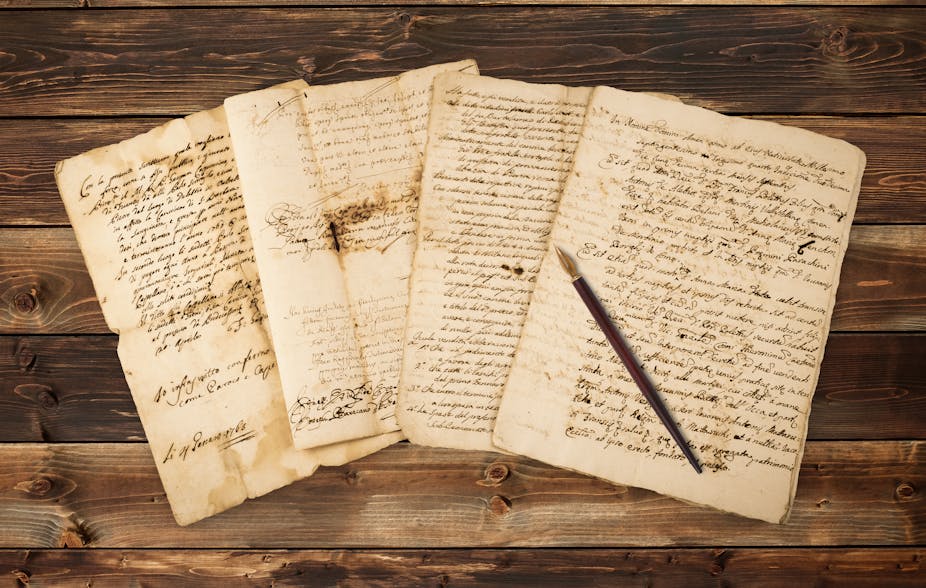

As such, correspondence played a central role in the pilgrims’ lives. It sustained friendships and kinship over immense distances. Letters extended social habits of communal worship, sharing spiritual knowledge and advice, and collective prayer that had once been practised in person.

Communal worship

Many of the Mayflower pilgrims had left England long before they set sail for the New World. They had radical religious beliefs and did not agree with the way the Church of England was run.

Do experts have something to add to public debate?

Looking for religious freedom, they fled to Leiden, the Netherlands. There, many worshipped at the Pieterskerk with their pastor, John Robinson. This group of refugees stayed in Leiden for 12 years. However, Holland was not as tolerant of their religious practices as they liked, and they began to fear the spread of the Thirty Years War that was overwhelming much of Europe.

In 1620, many of the group set sail again, this time for the New World. By then, they were a close community, and in 1625 those that had stayed behind expressed their grief that, “[they were] constrained to live disunited each from other, especially considering our affections each unto other”.

Puritans were intensely sociable in their worship. They believed that they belonged to a society of God’s saints. These were radical Protestants.

They had come together as minority groups in the face of criticism and ridicule from those around them. The name “puritan” was originally an insult, made by mocking neighbours poking fun at their intensely pious nature. With the sailing of the Mayflower, the separation of their close communities meant the disruption of the religious practices that defined them, particularly their emphasis on collective worship.

The Bible was a vital text for puritans and they felt strongly that they should study it together as often as they did privately. They did so constantly searching to learn more of God’s intentions for them.

In a practice called “gadding”, many puritans would travel to hear sermons given by ministers who believed the same things as themselves, since not everyone had access to a puritan preacher in their home parish or town. When unable to travel, they counselled each other. This happened in person where possible, but also in correspondence due to networks spread across Great Britain and the Netherlands.

Getting word across oceans

Puritan friendships were spiritual and social, and communion between friends provided emotional and material support. Their dispersal across England and the Netherlands made letter writing essential, even before emigration to the New World.

But these distances proved little in comparison to the Atlantic Ocean. With the prospect of a long term or permanent separation, puritans relied on their letters with increased urgency. Writing to her brother in law John Winthrop in 1629, Priscilla Fones expressed her fear at his impending departure:

… for though the bond of love still continues, the distance of the place will not let us be so useful one to another as now we are.

Correspondence provided the Leiden pastor John Robinson with a space to reassert his ties with his former congregants. In 1621, he wrote that “neither the distance of place nor distinction of body, can at all either dissolve or weaken that bond” between them. He vowed to maintain their spiritual connection with prayer and passed on well wishes from the wives and children of the emigrants, and others of the congregation who had stayed behind in Leiden.

Transatlantic correspondence came with many problems. Ships had to be available to carry these letters, while the journey was slow and the passage unreliable. Roger White, a citizen of Leiden, wrote to the pilgrims in 1625, lamenting that “I know not whether ever this will come to your hands, or miscarry, as other of my letters have done”.

Exercising caution, in 1630 John Winthrop, a leading figure among the Puritan founders of New England, sent news to his wife across two letters and sent it on different ships. These fears were not misplaced. News came to Massachusetts in 1633 that some other letters recently received in England had been washed “white and clean with saltwater” after the ship carrying them was wrecked.

The Mayflower pilgrims and those that later settled in other parts of New England were supported by their letters. They relied on them for the endurance of their friendships, and the lifting of their spirits. Words set in ink provided emotional support; letters were kept, stored, read and reread to bring absent loved ones to heart and mind.

Waiting aboard the Arbella at Southampton, on the eve of his departure for the new world, John Winthrop wrote to his wife. He told her that he often re-read her letters with “much delight”, although he found that he could not “read them without tears”. More than just words on a page, letters were an emotional and spiritual lifeline. Correspondence brought people together in familiar patterns of worship, despite their great distances.

No comments:

Post a Comment