What Does the Founding Era Evidence Say About How Presidential Electors Must Vote? – 5th in a Series on the Electoral College

- December 9, 2017

The

previous installment collected founding era evidence on whether

presidential electors were to control their own votes. The evidence

included dictionary definitions, existing practices, and the records of

the Constitutional Convention.

This installment continues the discussion of founding era by

collecting material from the public debates on whether to ratify the

Constitution. These debates occurred between September 17, 1787, when

the Constitution became public, and May 29, 1790, when the 13th state,

Rhode Island, ratified. Comments from those debates generally show that

the ratifiers understood presidential electors were to exercise their

own judgment when voting.

Probably the most-quoted statement from the public debate is from Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist No. 68:

A small number of persons, selected by theirThis is an important statement. However, for a number of reasons, we should not over-rely on The Federalist—or

fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess

the information and discernment requisite to such complicated

investigations. . . . And as the electors, chosen in each State, are to

assemble and vote in the State in which they are chosen, this detached

and divided situation will expose them much less to heats and ferments,

which might be communicated from them to the people, than if they were

all to be convened at one time, in one place.

on Hamilton, for that matter—when reconstructing how the public

understood the Constitution. Fortunately, there is a fair amount of

additional evidence.

Some of this material consists of comments stating merely that the

electors—rather than anyone else—would decide how to vote. In other

words, they assume the electors would remain independent.

For example, Roger Sherman, a delegate at Philadelphia and a

supporter of the Constitution, wrote that the president would be “re

eligible as often as the electors shall think proper.” An essayist

signing his name Civis Rusticus (Latin for “Country Citizen”) wrote that “the president was [chosen] by electors.” The Antifederalist author Centinel

asserted that the state legislatures would “nominate the electors who

choose the President of the United States.” The Antifederalist Candidus feared “the choice of President by a detached body of electors [as] dangerous and tending to bribery.”

In his second Fabius letter, John Dickinson—also described elector conduct in a way consistent only with free choice:

When these electors meet in their respective states,In Federalist No. 64, John Jay likewise implied elector choice and independence:

utterly vain will be the unreasonable suggestions derived for

partiality. The electors may throw away their votes, mark, with public

disappointment, some person improperly favored by them, or justly

revering the duties of their office, dedicate their votes to the best

interests of their country.

The convention . . . have directed the President to beSome participants emphasized that electors would remain independent

chosen by select bodies of electors, to be deputed by the people for

that express purpose; and they have committed the appointment of

senators to the State legislatures . . . As the select assemblies for

choosing the President, as well as the State legislatures who appoint

the senators, will in general be composed of the most enlightened and

respectable citizens, there is reason to presume that their attention

and their votes will be directed to those men only who have become the

most distinguished by their abilities and virtue, and in whom the people

perceive just grounds for confidence.

because the Constitution would protect them from outside influence. At

the North Carolina ratifying convention, James Iredell, later a justice

of the U.S. Supreme Court, spoke to the issue in a slightly different

context:

Nothing is more necessary than to prevent every danger ofAdvocates of the Constitution sometimes promoted the Electoral

influence. Had the time of election been different in different states,

the electors chosen in one state might have gone from state to state,

and conferred with the other electors, and the election might have been

thus carried on under undue influence. But by this provision, the

electors must meet in the different states on the same day, and cannot

confer together. They may not even know who are the electors in the

other states. There can be, therefore, no kind of combination. It is

probable that the man who is the object of the choice of thirteen

different states, the electors in each voting unconnectedly with the

rest, must be a person who possesses, in a high degree, the confidence

and respect of his country.

College as representing a viewpoint all its own rather than as

reflecting the will of others. Hence Hamilton’s observation in

Federalist No. 60:

The House of Representatives being to be electedSome participants discussed how electors might be appointed—whether

immediately by the people, the Senate by the State legislatures, the

President by electors chosen for that purpose by the people, there would

be little probability of a common interest to cement these different

branches in a predilection for any particular class of electors.

by the state legislatures or the people. For example, an essayist styled

A Democratic Federalist wrote, “our federal Representatives

will be chosen by the votes of the people themselves. The Electors of

the President and Vice President of the union may also, by laws of the

separate states, be put on the same footing.”

Yet such discussions of appointment were not accompanied by claims

that those who made the appointments would dictate the electors’ votes.

To be sure, William Davie, another Philadelphia delegate, said at the

North Carolina ratifying convention that “The election of the executive

is in some measure under the control of the legislatures of the states,

the electors being appointed under their direction.” But “in some

measure under the control” does not mean “wholly dictate.”

Possibly the closest anyone came to suggesting the legislatures would

direct electors’ votes was a comment by Increase Sumner at the

Massachusetts ratifying convention: “The President is to be chosen by

electors under the regulation of the state legislature.” However, it is

unclear what Sumner meant by “regulation.” He could be referring merely

to the fact that the legislature would “regulate” how electors were

appointed.

For those most part, moreover, participants worded their statements

in ways that avoided any suggestions that electors’ votes could be

controlled. In arguing for the Constitution, One of the People declared:

By the constitution, the president is to be chosen by ninety-one electors,Note how this is phrased: (1) the electors choose the president, (2)

each having one vote of this number . . . The constitution also admits

of the people choosing the electors, so that the electors may be only one remove from the people . . .”

the people may choose the electors, and if so (3) the choice of the

president will be “only one remove from [not “determined by”] the

people.”

At the Massachusetts ratifying convention Thomas Thacher asserted

“The President is chosen by the electors, who are appointed by the

people.” And in North Carolina Iredell argued that “the President is of a

very different nature from a monarch. He is to be chosen by electors

appointed by the people.” Again, observe the difference between

appointment and choice of the president.

A final point: When crafting the Electoral College, the framers were

careful to minimize opportunities for collusion, intrigue, or

“influence.” As James Iredell observed in the extract quoted above, one

element of the framers’ plan was to allow Congress to appoint a day for

appointment of electors and another day for voting. In each case,

however, “the Day shall be the same throughout the United States.”

Article II, Section 1, Clause 4.

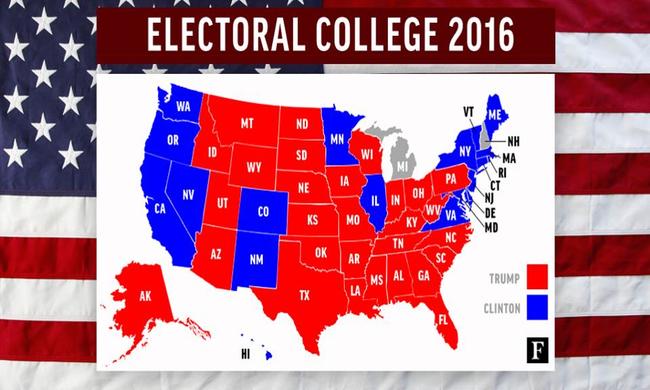

In 2016, the uniform day for the appointment of electors established

by Congress was November 8. But Colorado authorities removed an elector

and appointed in his alleged successor on December 19—manifestly not the

same day as November 8.

Not only did this violate the uniform day rule, but it was a classic

example of the kind of political maneuvering the rule was designed to

prevent.

No comments:

Post a Comment