Why Ferrari engineers don't like turbos

No turbos on the Bella Macchina, Signore

Oh. A rare moment of honesty, then a graceful slingshot into the same turbo spin we've heard from all corners of the globe. But this was the first time I'd heard a senior executive from a major carmaker admit that turbos are less than perfect.

"We don't like the turbo," said the man with the Italian accent

The fact

is, every car company is being forced into forced induction, for the

exact reasons our Italian friend gave. Since neither he nor the company

he works for, Ferrari, can come out and say it, I will: Turbos aren't

the best solution, especially for high-performance cars, and they don't

always provide the benefits that carmakers claim they do. Less

emissions, more performance? Let's take a look.REDUCING EMISSIONS

By

all rights, Ferrari shouldn't give a flaming tailpipe about mpg. But

governments are cracking down on CO2 emissions, and the only way to emit

less carbon dioxide is to burn less fuel. So even Maranello is looking

to the turbo to reduce fuel consumption.

The thing

is, while turbo engines perform well on standardized government

fuel-economy tests, out in the real world, we consistently see those

boosted engines using more fuel than larger, similarly powerful,

naturally aspirated ones. There's science behind our observations. The

stoichiometric ratio of air and gasoline is such that it takes 14.7

grams of air to completely combust one gram of gasoline. It's the job of

your car's fuel-injection system to measure the amount of air the

engine inhales and then provide precisely the correct amount of fuel.

By all rights, Ferrari shouldn't give a flaming tailpipe about mpg

Turbos, which are powered by

exhaust energy that is otherwise wasted, increase engine output by

forcing extra air into the cylinders, prompting the fuel injectors to

provide more fuel for combustion. More combustion, alas, means more

heat. To keep the engine (and turbo) from overheating, turbo engines

inject excess gas under boost. It seems counterintuitive, but this "rich

mixture" cools down combustion and reduces exhaust temperatures. It's

also a double-whammy fuel-economy killer, because burning that extra

fuel doesn't help the engine make more power, it actually reduces

output.

Government fuel-economy test cycles,

especially those in Europe, approximate the driving style of a heavily

sedated 83-year-old librarian. Since the engine is rarely taxed, the

turbo doesn't spool up, so no extra fuel is used. But purposely driving

slowly enough to keep the turbo from generating boost defeats the point

of having a turbocharger in the first place. Sadly, out in the real

world, riding that big, effortless wave of boosted midrange torque means

burning extra fuel—and creating even more CO2. So much for reducing

emissions.

NO REDUCTION IN PERFORMANCE

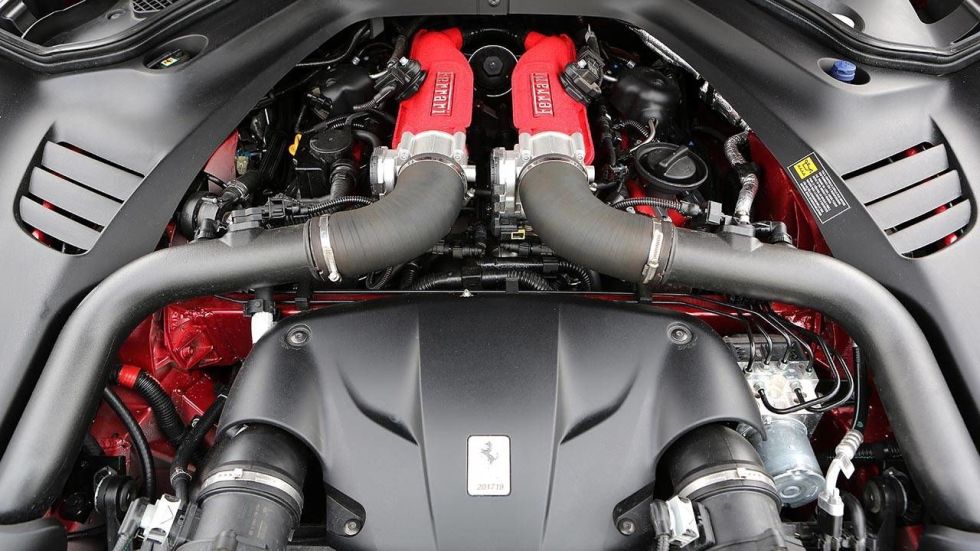

Performance, in this sense, refers solely to acceleration. The Ferrari California T's turbocharged 3.9-liter, 553-hp V8

easily outmuscles the old California's naturally aspirated 4.3-liter,

483-hp V8. Mission accomplished. Except there's more to an engine's

behavior than going fast in a straight line. The way an engine generates

power—its personality, if you will—is just as important as the number

of Mister Eds it replaces. For the entire history of the marque,

Ferrari's engines have delivered urgency and drama in lockstep with

revs, creating a festival of sound and fury as they raced toward a

stratospheric redline. Ferrari engines love to rev, which is one of the

main reasons we love Ferraris.

Immediate, predictable response is a requirement in any driver's car

Once there's a turbo impeller muffling the screaming glory of that

prancing horse, you're talking about an entirely different animal.

Engines with turbos big enough to provide boost throughout their

operating range produce peak torque at low revs and then gradually run

out of steam, like turbodiesels do. To combat that, gas-powertrain

engineers artificially create broad torque plateaus by limiting boost at

lower engine speeds. That electronic trickery helps the engine more

closely emulate a naturally aspirated one, but even that isn't enough

for Ferrari. The California T's computer also looks at gear position and

limits max boost in lower gears to encourage its driver to revel in the

revs.

Even so, clever programming can't fix the problem that has afflicted

turbochargers since the technology was invented: lag. Ferrari claims the

California's new turbo engine has "zero turbo lag" and "instantaneous

response," then defines response time as "less than one second." Really?

In a car that can hit 60 mph in three seconds, one second is anything

but instantaneous.Immediate, predictable response is a requirement in

any driver's car. Naturally aspirated engines react without delay to

throttle inputs, but a turbo engine is vastly more complicated. It has

two torque curves—one when it's off-boost and one when the turbo is at

full puff. The transition between the first curve and the second is what

we call lag—and both how long it takes and how abruptly it occurs

change continually.Despite the claims of marketers everywhere, lag

can't be eliminated. The holy grail for engineers of turbo engines—from

the 1962 Oldsmobile Jetfire to today's boosted cars—has been to manage

the lag so that it's unobtrusive in normal driving. Some engines do this

better than others. But when we're talking about Ferraris, who cares

about normal driving? When you're approaching the handling limit of a

well-balanced car, you need precise control of engine output. You may

need a quick jolt of torque to induce oversteer or to gradually increase

power to keep the car at its limit in a corner. These adjustments need

to happen the instant you request them and in direct correlation to

pedal input.A naturally aspirated engine's output is determined by the position of the pedal and the engine speed, period. Turbos change that into a complicated matrix with far too many variables for a driver to keep track of. At best, turbo lag is a handicap. At worst, it turns neutral, throttle-adjustable cars into insolent, uncontrollable, four-wheeled bastards.

Over the past 20 years, Ferraris have morphed from oil-spewing headaches into some of the best driver's cars money can buy. Drive a 458 Speciale or an F12 in anger, and by comparison almost every other car will feel removed, recalcitrant. Modern Ferraris do what you ask, when you ask, how you ask. They are pretty much perfect. Although their forthcoming turbocharged replacements will almost certainly be faster, I fear they will be undrivable without assistance from an onboard supercomputer.

Despite the claims of marketers everywhere, turbo lag can't be eliminated

To what end? There won't be any environmental

benefits, because Ferrari's contribution to worldwide automotive CO2

emissions is already effectively zero. (Toyota sells about as many

daily-driver Priuses in a week as Ferrari sells special-occasion sports

cars in a year.) It's sad that the marque feels compelled by government

policy to bolt turbos on to their lovely engines, when it won't make a

whit of difference to air quality.And it's doubly sad that we all know it will change the way Ferraris drive.

So while I was genuinely ready to cheer Ferrari for that momentary showing of honesty, I'm still waiting to hear some auto-company executive unabashedly tell the whole truth: "We don't like turbos," the speech will begin, "and so we're not going to use them."

My applause may have to wait.

No comments:

Post a Comment