What you might not know about the 1964 Civil Rights Act

MLK and Malcolm X met only once? 01:56

Story highlights

- Wednesday marks the 50th anniversary of the signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

- "It changed everything about ordinary life for black Americans," says Todd Purdum

- The act holds the record for sparking the longest filibuster in the history of the U.S. Senate

This story was originally published April 10.

(CNN)The

Civil Rights Act of 1964 -- hailed by some as the most important

legislation in American history -- was signed into law 50 years ago

Wednesday.

It was

known as the "bill of the century." But many Americans today probably

couldn't say exactly what the legislation accomplished.

"It's really the law that created modern America," said Todd S. Purdum, author of "An Idea Whose Time Has Come."

"Its goal was to help finish the work of the Civil War, 100 years after

the war had ended, and to make the promise of legal equality for blacks

and whites, even though actual equality is elusive to this day."

The

law revolutionized a country where blacks and whites could not eat

together in public restaurants under Jim Crow laws, or stay at the same

hotel. It outlawed discrimination in public places and facilities and

banned discrimination based on race, gender, religion or national origin

by employers and government agencies. It also encouraged the

desegregation of public schools.

"This

did all of those things. It changed everything about ordinary life for

black Americans all over the country," Purdum said. "I think when you

try to explain to people today -- I have children 10 and 14 years old,

and I don't think they can really imagine a world like (this) existed

before this law."

The act had the longest filibuster in U.S. Senate history,

and after a bloody, long civil rights struggle, the Senate passed the

act 73-27 in July 1964. It became law less than a year after President

John F. Kennedy's assassination.

Here are a few surprising facts about how the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law:

1. More Republicans voted in favor of the Civil Rights Act than Democrats

In the 1960s, Congress was divided on civil rights issues -- but not necessarily along party lines.

"Most

people don't realize that today at all -- in proportional terms, a far

higher percentage of Republicans voted for this bill than did Democrats,

because of the way the Southerners were divided," said Purdum.

The division was geographic. The Guardian's Harry J. Enten broke down the vote,

showing that more than 80% of Republicans in both houses voted in favor

of the bill, compared with more than 60% of Democrats. When you account

for geography, according to Enten's article, 90% of lawmakers from

states that were in the Union during the Civil War supported the bill

compared with less than 10% of lawmakers from states that were in the

Confederacy.

Enten points out that Democrats still played a key role in getting the law passed.

"It

was also Democrats who helped usher the bill through the House, Senate,

and ultimately a Democratic president who signed it into law," Enten

writes.

2. A fiscal conservative became an unsung hero in helping the Act pass

Ohio's Republican Rep. William McCulloch had a conservative track record -- he opposed foreign and federal education aid and supported gun rights and school prayer.

His district (the same one now represented by House Speaker John

Boehner) had a small African-American population. So he had little to

gain politically by supporting the Civil Rights Act.

Yet he became a critical leader in getting the bill passed.

His ancestors opposed slavery even before the Civil War, and he'd made a deal with Kennedy to see the bill through to passage.

"The Constitution doesn't say that whites alone shall have our most basic rights, but that we all shall have them," McCulloch would say to fellow legislators.

Later,

he would play a key role in the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the 1968

Fair Housing Act and become part of the Kerner Commission, appointed by

the Johnson administration to investigate the 1967 race riots.

Kennedy's widow, Jacqueline Kennedy, wrote him an "emotional" letter when he retired from Congress in 1972.

"You

made a personal commitment to President Kennedy in October 1963,

against all interests of your district," she wrote. "There were so many

opportunities to sabotage the bill, without appearing to do so, but you

never took them. On the contrary, you brought everyone else along with

you."

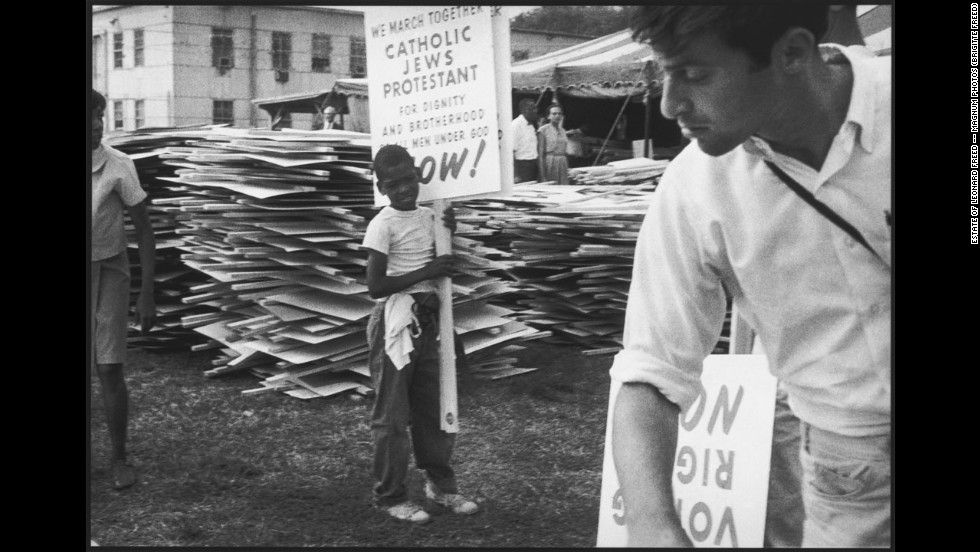

3. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. met for the first and only time during Senate debate on the act

The two leaders met briefly on March 26, 1964,

while they were both on Capitol Hill to hear debate on the 1964 Civil

Rights Act. That brief encounter was captured by photographers.

"Well, Malcolm, good to see you," King greeted Malcolm X.

"Good to see you," he replied.

Known

for his direct rhetoric in denouncing America's treatment of

African-Americans, Malcolm X was a stark contrast to King, who preached

tolerance and peace in achieving equal rights.

Some

scholars say the two could have formed an alliance, as Malcolm X moved

away from the Nation of Islam. But it never happened: Malcolm X was

shot and killed less than a year after their first and only encounter.

King was assassinated in 1968.

4. The act didn't help just black Americans

Women,

religious minorities, Latinos and whites also benefited from the Civil

Rights Act, which would later serve as a model for other

anti-discrimination measures passed by Congress, including the Americans

with Disabilities Act and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act.

Under

the Civil Rights Act, women who had been fired because they became

pregnant, or were not hired because they had small children, now had

recourse. As a result of Title VII, "male only" job notices became

illegal for the first time.

Before the Civil Rights Act, women made up less than 3% of attorneys and less than 1% of federal judges; now they make up nearly a third of lawyers, according to the National Jurist, and three of the nine Supreme Court Justices are women.

The

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was also created by the law,

giving women a workable "hammer" with which to shatter the glass

ceiling.

5. A segregationist congressman's attempt to kill the bill backfired

Virginia's Democratic Rep. Howard W. Smith was a staunch segregationist and strongly opposed the Civil Rights Act.

Smith,

who was chairman of the House Rules Committee, came up with many

tactics to discourage the passage of the bill's Title VII, which would

outlaw employment discrimination because of race, color, religion or

national origin.

When Smith added the word "sex," the House reportedly laughed out loud.

The ploy was Smith's attempt to quash support among the chamber's male

chauvinists on the grounds that the bill would protect women's rights in

the workplace, according to Clay Risen in his book "The Bill of the Century."

Despite

resistance, and complex motives, the act eventually passed, laying the

groundwork for legal battles to ensure equal employment opportunities

for women.

And whether he intended to or not, Smith ended up helping to set the stage for modern feminism.

6. The 1964 law didn't do much to address discrimination at the ballot box

Black

men were granted the right to vote in 1870 under the 15th Amendment

(women followed 50 years later). Yet many obstacles -- including

literacy tests and poll taxes -- prevented most blacks in the South from

casting ballots.

Just a few

months before the Voting Rights Act, the 24th Amendment to the U.S.

Constitution was ratified to remove poll taxes as a condition for voting

in federal elections. All the 1964 Civil Rights Act did was to mandate

the same voting rules nationwide.

It wasn't until the following year that the 1965 Voting Rights Act would suspend the use of literacy tests.

No comments:

Post a Comment