The unsurprising failure of Denver’s ‘affordable housing’ ordinance

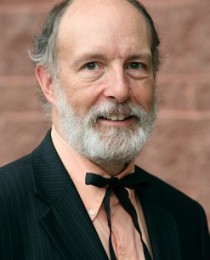

By Randal O'Toole

Denver’s urban-growth boundary has made housing expensive. More than a decade ago, the city blamed “failure by the private market to produce enough affordable housing” (see p. 5). To fix this “failure,” the city required developers to build “affordable housing.” Now, the city admits that this ordinance is a failure.

Data from the 2011 American Community Survey indicates that the median value of owner-occupied homes in Denver is nearly four times median family incomes. It should be just two times, which is typical for cities that don’t have urban-growth boundaries or other restrictive land-use laws. So housing prices are nearly twice as high as they ought to be.

As this city document explains, Denver’s “inclusionary zoning” ordinance requires developers who build 30 or more homes or condos at one time to sell at least 10 percent of those homes at “affordable” prices. Typically, this means an average of about $40,000 less than market prices, which is likely below the actual cost of constructing the homes. To make up for the losses, developers have to sell the remaining 90 percent for more than they would otherwise.

The people who buy these homes don’t really get a windfall. They are required to live in the houses themselves (i.e., they can’t rent them out at market rates) and, if they sell them within 15 to 30 years after buying them, they can’t sell them for more than they paid for them plus inflation. None of the buyers are really poor; anyone who earns up to 80 percent of the city’s median income is eligible. It is likely that many of the buyers are young people whose lifetime earnings are likely to be well above median incomes.

The number of “affordable” homes that were built under this ordinance is pathetic. About 55 units were build in 2007, but the average for every other year since 2005 has only been about five units per year. That’s a total of about 100.

The city claims that more than 1,100 units were built under the ordinance, but it is counting 1,056 units built as a part of city-subsidized developments such as Stapleton and Lowry (former airports converted, at city expense, to “New Urbanist” housing projects). Most were built in Green Valley Ranch, a development east of Denver on land annexed into the city. Developers received incentives to make about 650 homes “affordable.”

Where did the city get the money to offer these incentives to Green Valley developers? From other developers who paid the city millions to opt out of the inclusionary zoning program. Ultimately, of course, those millions were paid by new homebuyers, which means the inclusionary zoning ordinance actually increased the cost of new housing. Since the prices of used homes follow new home prices, the affordable housing ordinance made Denver housing less affordable.

This is not surprising: economists at San Jose State University proved this is what happened to cities that adopted inclusionary zoning ordinances in California. They noted that not only did such ordinances drive up the cost of new homes, they led developers to build fewer new homes than they would otherwise.

Although the city admits that the ordinance has failed, it uses the wrong measure for success. Instead of counting the number of “affordable” units built, it should look at the overall affordability of the city’s housing. The 2010 census found that Denver has more than 263,000 occupied housing units, so adding a few hundred “affordable” units to the mix is really not going to make any difference. The real problem is that the ordinance makes all the rest of the housing even less affordable.

Denver’s likely solution is to make the ordinance even stronger by increasing the percentage of affordable homes that must be built, reducing the minimum number of homes that triggers the ordinance to less than 30, or taking away developers’ ability to opt out by paying the city money. This will simply make the problem worse. Instead, Denver should tell the Denver Regional Council of Governments to abandon the region’s urban-growth boundary and let people live where they like.

Randal O’Toole is director of transportation policy at the Independence Institute, a free-market think tank in Denver, and a senior fellow at the Washington, DC-based Cato Institute. This op-ed originally appeared in the Antiplanner blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment